ART NEWS

The True Story of How Dumbo Came to the Screen | Innovation

[ad_1]

As Dumbo soars into theaters this week with a new Disney live-action movie, it is interesting to note that it was a simple twist of fate that brought this beloved classic to the silver screen in the first place.

Actually, it was a twist of the wrist.

The story of the baby elephant with very large ears who must overcome adversity and ridicule to become a circus star was originally planned as a children’s book. However, this was no ordinary hardcover. It was intended to be published as a novelty book with illustrations printed on a long scroll contained in a box. To follow the story, readers would twist dials on the outside of the box until the next frame with pictures and words came into view.

Roll-A-Book Publishers, Inc. of Syracuse, New York, acquired the rights to publish Dumbo from author Helen Aberson and her then-husband, Harold Pearl, who was the illustrator. Two or three prototypes were created in the scrolling-book format. However, before it could go into production, the story idea was sold in 1939 to Disney Productions, which purchased all intellectual property rights, including book publishing.

Aberson, who died in 1999, was proud of her story, which was tinged with sadness but demonstrated how perseverance triumphs in the end. Her son believed Dumbo was a metaphor for his mother’s own experience. “At times her life was difficult,” Andrew Mayer says. A first-generation Russian-American, her Jewish family struggled through poverty and bigotry to make its way in a new country.*

Of course, Disney turned Dumbo into a successful animated film in 1941 that has tugged at heartstrings for generations. The new film version, reimagined by director Tim Burton, combines live action with computer-generated imagery to create a whole new look for this delightful tale. It stars Eva Green, Colin Farrell, Danny DeVito, Michael Keaton and Alan Arkin.

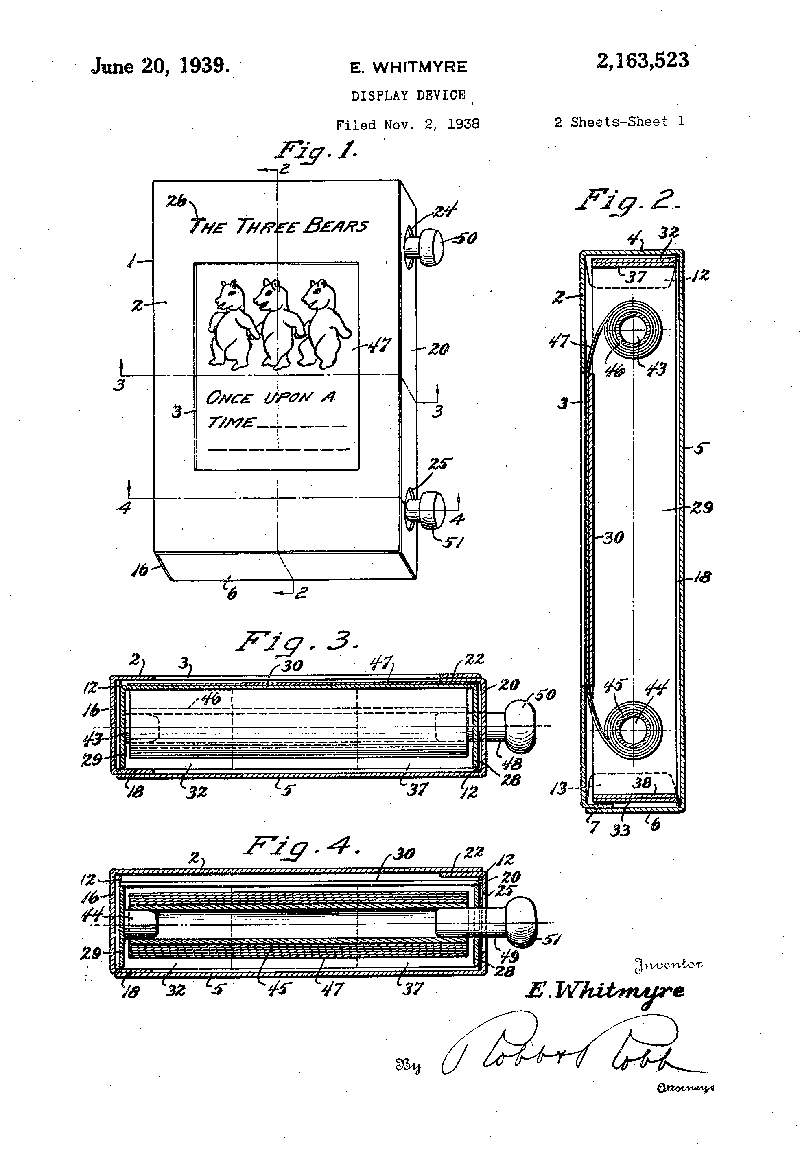

The scrolling-book concept was conceived by Everett Whitmyre, a Syracuse advertising agent who was known as “an ideas man.” He was said to have gotten the idea from watching children at the New York Public Library. Whitmyre applied for a patent in 1938, which was granted the following year. He assigned the patent rights to his own Roll-A-Book Publishers, Inc.

Whitmyre detailed his concept’s attributes in the patent application: “My invention may be characterized as a book, yet it is endowed with a number of novel features which is not found in an ordinary book,” adding “…the rolls are manipulated to wind the strip or sheet from one roll onto the other roll.”

(U.S. Pat. No. 2,163,523)

Whitmyre became interested in Dumbo after Aberson and Pearl approached him to publish the book. The couple, who had married in 1938, was excited by the possibility of a scrolling book. Aberson had come up with the Dumbo idea and written the story while Pearl did the initial drawings.

Helen Durney, an artist who worked for Roll-A-Book, was given the task of redrawing the images to fit the scrolling book format. She did several rough illustrations that were used to make the two or three prototypes of how Dumbo would appear in this new publishing format. Galley proofs of her original artwork are housed in Bird Library at Syracuse University.

However, before the book could be printed, Whitmyre offered the story to Walt Disney, the celebrated movie animator and creator of Mickey Mouse. He recognized the potential for a film and quickly worked a deal with Aberson and Pearl. It is believed one of the prototypes had been sent to Disney Productions in Hollywood. If it was, the studio no longer has it in its archives.

Durney also may have assisted Disney with some of the early conceptual drawings for the animated movie. However, once production got underway, Aberson went to Hollywood to serve as a consultant on the film. Disney records do not show she was on the payroll but Aberson and Pearl, who she divorced in 1940, did receive a one-time fee for the story rights.

Dumbo went on to be a critical and commercial success at the box office, generating more than $1 million in profits. That windfall likely saved Disney from financial ruin, which had suffered an animators’s strike in 1941 and was feeling the pinch from the loss of the European market as a result of World War II.

In its review of Dumbo, The New York Times reported it was “the most genial, the most endearing, the most completely precious cartoon feature film ever to emerge from the magical brushes of Walt Disney’s wonder-working artists!”

The movie is now a classic, a favorite of young and old alike. As for Roll-A-Book, that idea never really caught on. Only one book was published in the twist-of-the-wrist format and it had only limited success. Titled The Last Stone of Agog, the scrolling book was promoted as “a fast paced adventure story packed with mystery and surprises.”

However, Dumbo did eventually take off as a children’s book. It was published in 1941 and again in 1947 by Little Golden Books under a licensing agreement with Disney. It hasn’t been out of print since. New adventures and storylines were created for additional books about everybody’s favorite flying elephant, who continues to soar across the pages—and now into a new movie.

Aberson and Pearl were credited on the original book as the authors. They retained that distinction until 1968, when the original copyright expired. After that, Disney no longer included their names on the book, which deeply saddened Mayer’s mother.

Over time, confusion arose over who did what in creating the Dumbo saga. Pearl started getting credit as a co-author and Durney was often recognized as playing more of a role than she did. Mayer says he discussed the book with his mother on several occasions and she was adamant it was her brainchild.

“She swore that her first husband Harold ‘really just did the illustrations for the book, but the ideas were entirely mine,’” he says, “and I believed her.”

*Editor’s Note, March 27, 2019: A previous version of this article incorrectly described Helen Aberson as Polish-American, when, in fact, she was Russian-American. The story has been edited to correct that fact.

[ad_2]

Source link