ART NEWS

Women’s Voices Ring With a Resounding Roar in This New Show | At the Smithsonian

[ad_1]

SMITHSONIAN.COM |

July 16, 2019, 1:19 p.m.

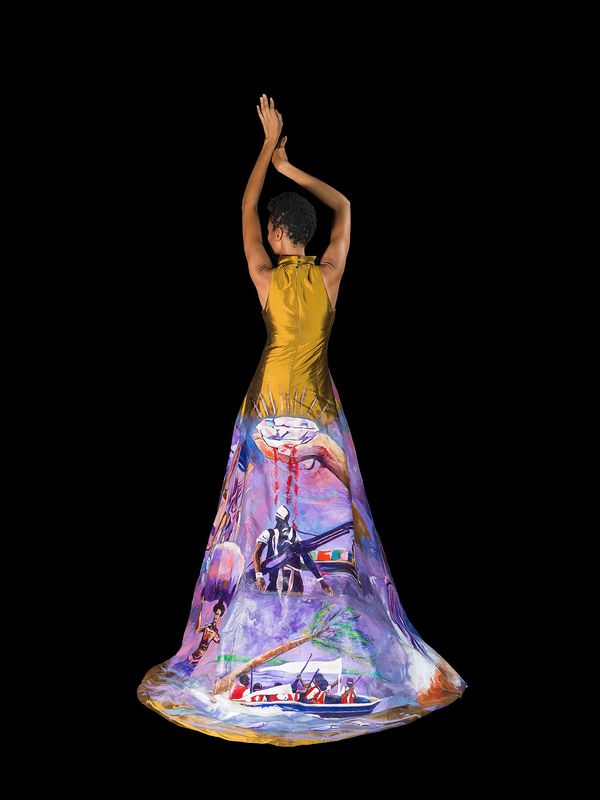

Patience Torlowei gasps as she turns the corner in the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art to see her centerpiece work Esther for the first time in five years.

“Please bear with me, because I can’t contain myself,” she says. Named after her then-recently deceased mother, the hand-painted gown depicting vivid scenes of mineral extraction along with war scenes, was the first haute couture work to be acquired by the museum.

Today, it’s on display again in a lively, year-long showcase at the museum and titled: “I Am … Contemporary Women Artists of Africa.”

Esther, which Torlowei says was “about the truth of what’s going on in Africa,” represents a difficult time in her life, in part because she could not bear to sell the work. “This is about Africa. This is about my mother,” she says. “I may be broke, but if I sell this dress, I’m selling the story of Africa. I want people to learn from it.”

(African Art Museum, gift of the artist)

(African Art Museum, gift of the artist)

So Torlowei, who has since become a renowned Nigerian fashion designer, donated Esther to the African Art Museum, where it joins 29 other artworks in the show by 27 contemporary artists representing 10 countries.

It’s only a fraction of the total of works by women artists held in the African Art Museum’s collections, says curator Karen E. Melbourne. But many of the pieces are on display for the first time.

“I Am…,” which takes its title from Helen Reddy’s 1971 pop music hit “I Am Woman,” is part of the museum’s Women’s Initiative Fund, an effort to increase the visibility of female artists in its shows, publications, partnerships and in its collections. An assessment seven years ago found that just 11 percent of the named artists represented in the collections were works by women.

“We immediately recognized that wasn’t okay,” says Melbourne. An effort after that finding doubled the number to 22 percent, but the effort is ongoing, she says.

(African Art Museum, gift of Patricia A. Bell)

“This museum has been ahead in trying to identify these issues, recognize [the museum’s] history, and share our history so that other institutions can do differently, better, moving forward,” Melbourne says.

“This is a really special exhibition,” adds the museum’s director Gus Casely-Hayford. “I felt changed by it, but also really inspired by it.”

Some of the oldest pieces in the show are derived from textile art, crafts like weaving and dyeing that African women embraced by tradition. In Nigeria, Chief Nike Davies-Okundaye used the expressive patterns and textures as a background for her drawing and painting, as in the diptych displayed, Liberal Women Protest March I & II. Atop patterns in a Yoruba textile art known as adire, she painted a group of women gathered at a nonviolent demonstration.

“You communicate with what you are wearing,” says Davies-Okundaye, who strolled the exhibition in a vivid headdress. “Especially this color red, which is for power,” she says, pointing at her work. “Nigerian women are very, very powerful.”

Billie Zangewa’s self-portrait in silk, “Constant Gardener,” depicts the artist harvesting Swiss chard, drawing on the agricultural past of her ancestors and also reflecting a personal philosophy. “It’s about tending to my son, tending to myself, my life and who I am,” says Zangewa, a Malawian-born artist who lives in South Africa. Zangewa, who has been fascinated by fashion since childhood, briefly crafted purses and handbags and worked in fashion and advertising before returning to the visual arts. Melbourne says the piece “shows her ability to move between fashion and fine arts and to speak to a truly individual experience that speaks to each and every one of us.”

(African Art Museum )

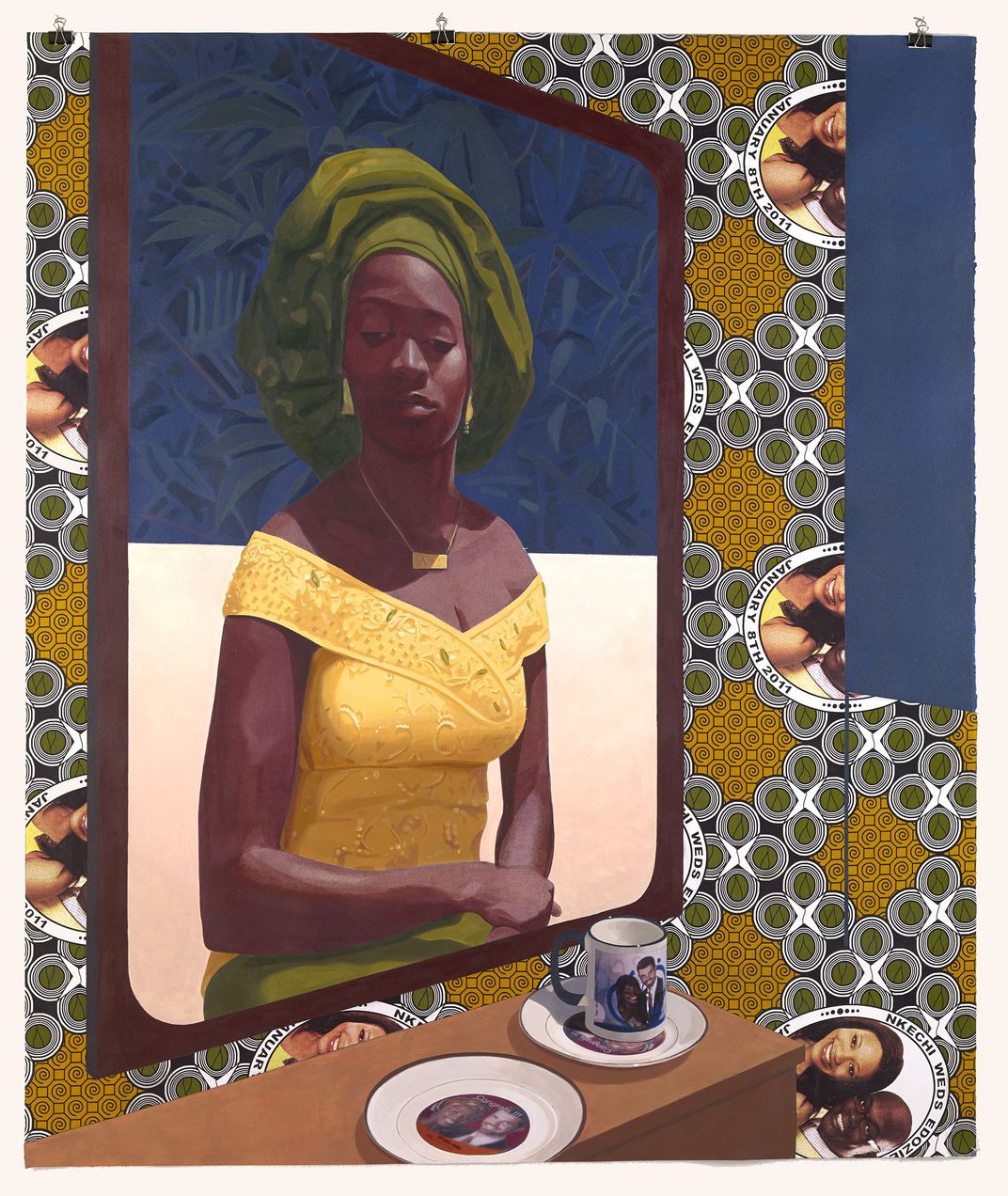

Fabric is not the only medium in the wide-ranging, multi-media show. In Njideka Akunyili Crosby’s 2016 Wedding Souvenirs, a collage with acrylic, the artist depicts scenes from a Nigerian wedding, but in addition, Melbourne says, you also see “a woman who is completely composed. She is in possession of her space. She is not looking at us, she is looking into herself for all that she can contribute.” As such it’s the first image seen in the show. “It seemed to sum up the experience of ‘I Am,’” Melbourne says. “You see a woman in full possession of that phrase.”

(African Art Museum )

Nearby is an eye-catching sculpture from Moroccan artist Batoul S’Himi. Her 2011 piece Untitled from her “World Under Pressure” series is an actual pressure cooker with a map of the world cut from its side. It speaks of the “mounting pressure to give women their due,” the curator says.

The South African artist Nompumelelo Ngoma presents a near abstract monoprint, Take Care of Me, that examines the complexities of a wedding gown pattern in more ways than one.

Women are wrapped in stiff lace at a funeral depicted in Nigerian artist Sokari Douglas Camp’s brightly-colored mixed-media work, Sketch for Church Ede.

(African Art Museum )

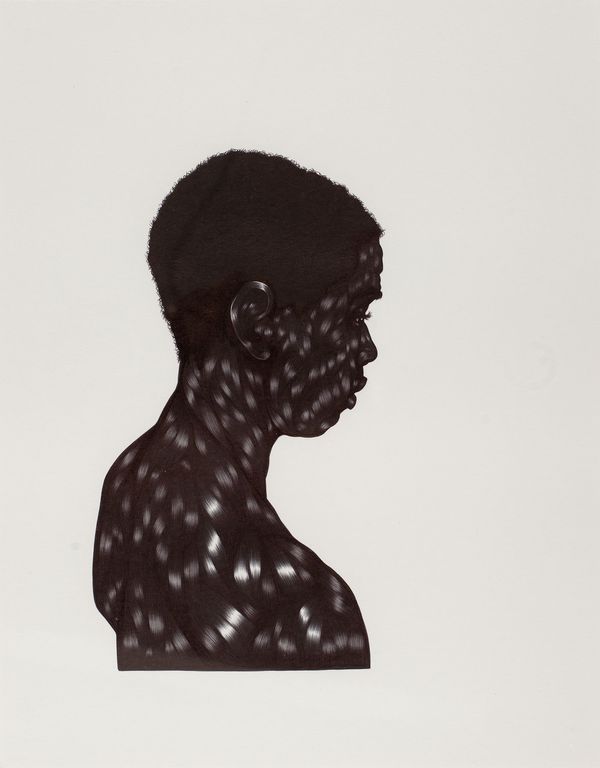

Nigerian-born artist Toyin Ojih Odutola presents a compelling profile Untitled (D.O. Back Study), a seeming silhouette done entirely in densely drawn ballpoint pen. It’s among a number of unconventional methods in the exhibition—but none more than Diane Victor’s remarkably representational Good Shepherd, rendered entirely with the smoke of a candle.

South African artist Frances Goodman deconstructs the amorous traditions of the car back set with her Skin on Skin, whose title is spelled out in faux pearls across a car seat minus its stuffing. “They hang on the wall, almost like skins—like these deflated icons,” Goodman says. “With their pomp and ceremony taken out of them.”

(African Art Museum )

(African Art Museum )

Helga Kohl depicts the remains of a ghost town after a nearby diamond mine in Kolmanskop, Namibia, was exhausted and abandoned, the surrounding sands now reclaiming bedrooms. “One day I knew I was ready to capture the beauty once created by people and taken over by nature,” she says.

There are a couple of life-sized figures in the exhibition. Kenyan artist Wangechi Mutu fashions her Tree Woman with earth, pulp stone and branches. Adejoke Tugbiyele’s 2015 Past/Future fashions a bent figure from brooms, strainers and wire.

(African Art Museum )

Among the photographic images, South African Zanele Muholi seeks to make black lesbians more visible. “I’m basically saying that we deserve recognition, respect, validation and to have publications that mark and trace our existence,” the artist says in a statement.

Some incidents are better known than others. Senzeni Marasela depicts in red thread on linen the history of Sarah Baartman, the 19th-century African woman that was put on display in Europe as a curiosity, while Sue Williamson commemorates a lesser known multiracial neighborhood demolished by South Africa’s apartheid government in her 1993 The Last Summer Revisited.

Penny Siopis takes a notorious story, of a nun murdered by a crowd following an anti-apartheid protest, and illustrates it with found home movies in her 2011 video Communion. It is, she explains, “about an individual caught up in a larger, political context, but it’s elemental enough. . . to see, or to envisage in it, a way to speak beyond the specific historical and political moment.”

“I Am … Contemporary Women Artists of Africa” continues through July 5, 2020 at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C.

[ad_2]

Source link