ART NEWS

When Twister Was Too Risqué For America | Innovation

[ad_1]

The original box for the game Twister was jarring in its conservatism. Although the game was marketed mostly to kids and teens, emblazoned across the promotional material for its 1966 launch were cartoon adults wearing fancy clothes entirely impractical for playing the game. Also inexplicably for a game premised on close contact, the adults left a healthy distance between their bodies.

“The men are in full suits and ties, all the way up to their necks. The women have sweaters, buttoned up to their necks,” says Tim Walsh, who wrote about the history of toys in his book The Playmakers. “There was no skin showing at all.”

That strange design existed for a reason. The makers of Twister, the board game manufacturer Milton Bradley Company, feared that parents would deem the game inappropriate for kids because of the close physical proximity of its players. To deflect from concerns around sexual undertones, they packaged it as inoffensively as possible. Nothing screamed “sex!” less than overdressed cartoon adults.

The game’s champion from within Milton Bradley, development executive Mel Taft, pushed Twister into the market even as others in his company said the game wasn’t worth the risk.

(Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

“He got quite a bit of flak from people internally at Milton Bradley,” says Walsh, who interviewed Taft for his book. Most of that internal criticism took an exacting form—Milton Bradley’s brand revolved around making tabletop games, and Twister was a floor game—but a strand of it centered on the concerns that the game would be perceived as too sexual. “He did share that there were some people internally that thought it was a little risqué for kids,” says Walsh.

As Taft put it to The Guardian shortly before his death, “When I showed it to my sales manager, he said: ‘What you’re trying to do there is put sex in a box.’ He refused to play. He said it was too far out, kids wrapping themselves around each other like that.”

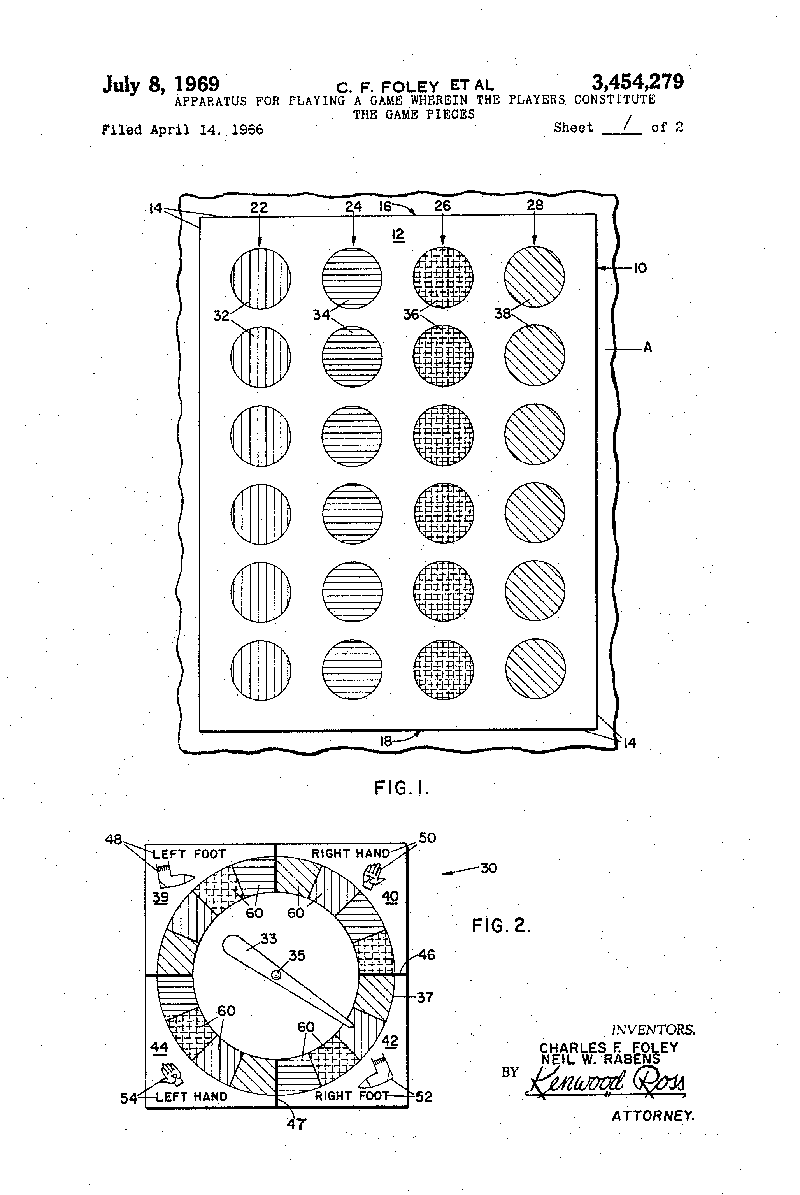

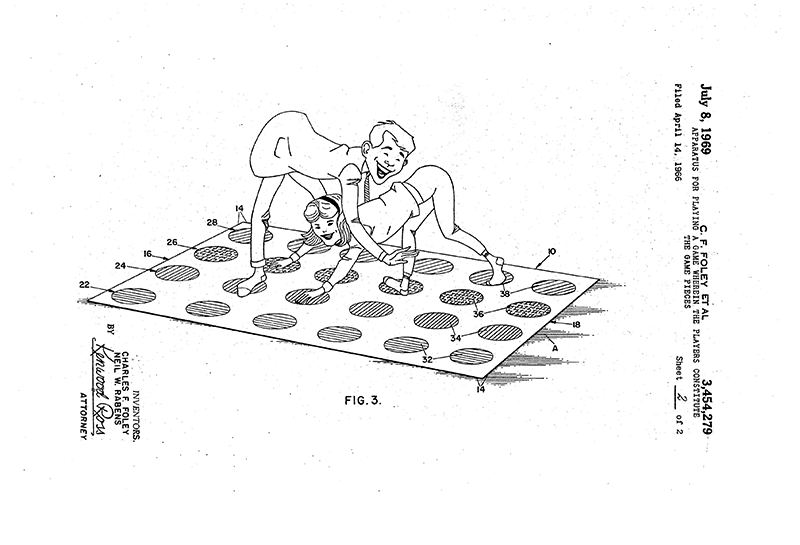

Although Twister launched earlier, in April 1966, this week marks the 50th anniversary of its patent. Charles Foley and Neil Rabens, the two inventors credited on the patent, were working at a Minnesota design firm named Reynolds Guyer House of Design when they developed the game. The initial spark began with the firm’s owner, Reyn Guyer, who in 1964 envisioned the polka-dot board, and he tasked Foley and Rabens with turning it into a functioning game. Foley, an inventor by trade, decided that people should act as the pieces; Rabens, a designer, created the board.

(U.S. Patent 3,454,279)

In the patent, the duo boiled down the game to a mechanical description that verged on absurdity, noting that “with a particular limb of each player on a particular locus of a certain column, and with the referee chancing to call for the movement of the said limb to a locus of the same column, the players shall each be required to move that same limb to another locus of that same column.”

But that description was confusing enough that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office asked Rabens and Foley to demonstrate how the game worked in person—which the pair happily agreed to do.

After filing the patent and bringing the idea to Milton Bradley, design firm owner Reyn Guyer feared the concern over the game’s undertones meant it would never be released. “They warned Mel that the idea of being that close to someone––especially someone of the opposite sex––was socially unacceptable,” Guyer wrote in his book Right Brain Red. “The rule we were breaking almost broke the deal. Thankfully, Mel Taft was a rule breaker too.”

(U.S. Patent 3,454,279)

When Milton Bradley did eventually distribute the game, those internal fears seemed to manifest. For weeks, few consumers would touch it. Sales flat-lined. At the annual Toy Fair in New York in 1966, even buyers from department stores across the United States expressed their skepticism. But most damning of all, Sears resisted stocking it because, their representative said, the game was “too risqué.”

That decision could not have been more devastating. “If Sears said we’re not buying this, it could be the death of a game because they had such a monopoly,” says Walsh. After hearing the news, Guyer wrote that “Twister was dead.”

Twister’s saving grace came a month after its formal release, when late-night host Johnny Carson and actress Eva Gabor agreed—thanks to a savvy pitch from a Milton Bradley salesperson—to play Twister on Carson’s show in May 1966. The lasting image of the two contorting their bodies before a national audience sent sales skyrocketing, and by 1967, Milton Bradley had moved over 3 million copies. Sears started stocking it. Twister’s subversion of taboos around personal space, no longer fatal baggage, quickly became one of its biggest assets. Today, the game is a global sensation, with its new owner Hasbro citing it as one of its top sales performers in the first quarter of 2019 and the National Toy Hall of Fame honoring it as a 2015 inductee.

According to Walsh, the inventors of the game had a mantra they would repeat again and again in subsequent years: “Clean mind, clean game. Dirty mind, dirty game.”

Like this article?

SIGN UP for our newsletter

[ad_2]

Source link