ART NEWS

What Makes Francisco Toledo ‘El Maestro’ | Arts & Culture

[ad_1]

When Francisco Toledo heard that a McDonald’s was to open in the elegant, nearly 500-year-old Zócalo, or town square, the heart of Oaxaca City, he devised an ingenious method of protest: He announced that he would take off all his clothes and stand naked in front of the site of the proposed Golden Arches. And to remind Mexicans of the pleasures of their own food he would enlist the help of some fellow artists and hand out free tamales to anyone who joined the protest.

“We resisted with him,” the Oaxacan painter Guillermo Olguín told me. “We showed that civil society has a voice. We bought banana leaves. I made some posters. We were the soldiers to represent the people. We set up tables. It was a happening!”

Hundreds of people marched in the 2002 event, raised their fists and chanted, “Tamales, yes! Hamburgers, no!” In the end, there was such a public outcry that Toledo did not find it necessary to take off his clothes—the tamales did the trick.

In 2014, Toledo protested again, over a far more serious matter, the disappearance of 43 students in Ayotzinapa, in the state of Guerrero, presumably murdered by the local police, with the connivance of drug cartels. When it seemed that no one in the government cared very much (and indeed might have been involved), Toledo painted portraits of the students on 43 kites, and encouraged people in Oaxaca to fly these works of art as protests. And so “Ayotzinapa Kites” was another happening that raised awareness as it memorialized the victims.

“He’s a giant,” Olguín said. “All the people in Mexico involved in the creative process should be grateful to him.”

(Trine Ellitsgaard)

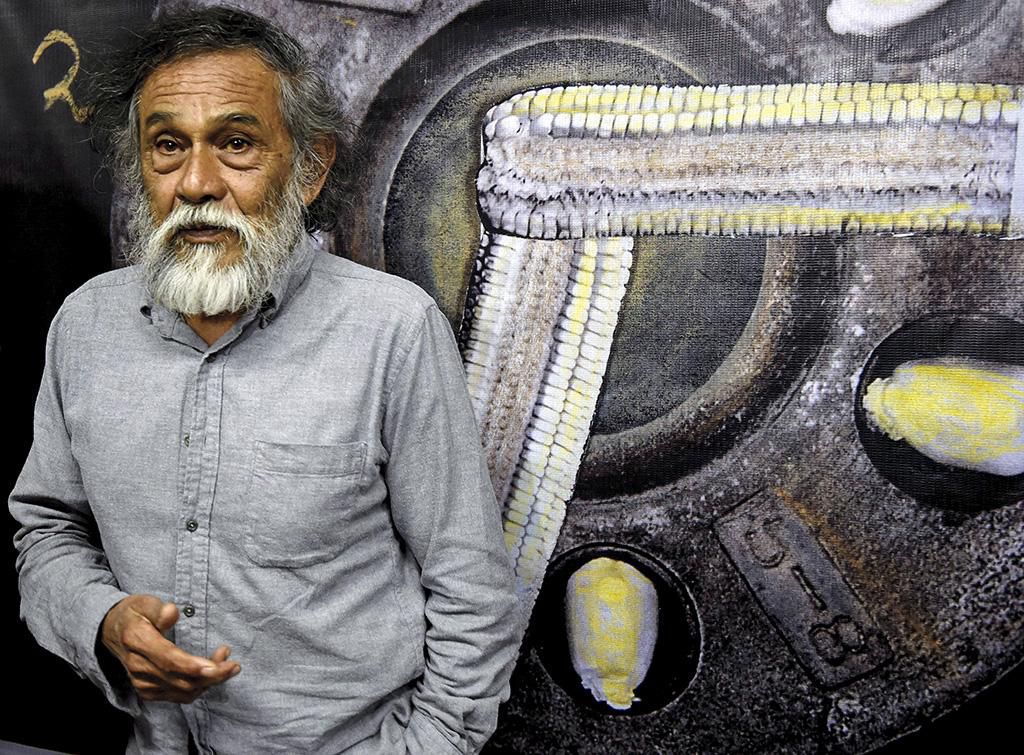

An artist, an activist, an organizer, the embodiment of Oaxaca’s vortex of energy, and a motivator, Toledo is known as El Maestro. That is an appropriate description: the master, also teacher and authority figure. His work, and the results of his campaigns and his philanthropy, can be seen everywhere; but the man himself is elusive. He hides from journalists, he hates to be photographed, he seldom gives interviews, he no longer attends his own openings, but instead sends his wife and daughter to preside over them, while he stays in his studio, unwilling to speak—a great example of how writers and artists should respond—letting his work speak for him, with greater eloquence.

It is said that Toledo courts anonymity, not celebrity. He is that maddening public figure, the person so determined to avoid being noticed and to maintain his privacy, that he becomes the object of exaggerated scrutiny, his privacy constantly under threat. It is the attention seeker and the publicity hound who is consigned to obscurity—or ignored or dismissed. The recluse, the shunner of fame, the “I just want to be alone” escapee—Garbo, J.D. Salinger, Banksy—seems perversely to invite intrusion. Say “Absolutely no interviews,” and people beat a path to your door.

Fascinated by his work and his activism, I was provoked to become one of those intruders. Incurable nosiness is the true traveler’s essential but least likable trait. I put in a request to see Toledo, through his daughter, Sara, and looked further into Toledo’s public life.

(Galería Juan Martín / Photo Courtesy Galería Arvil)

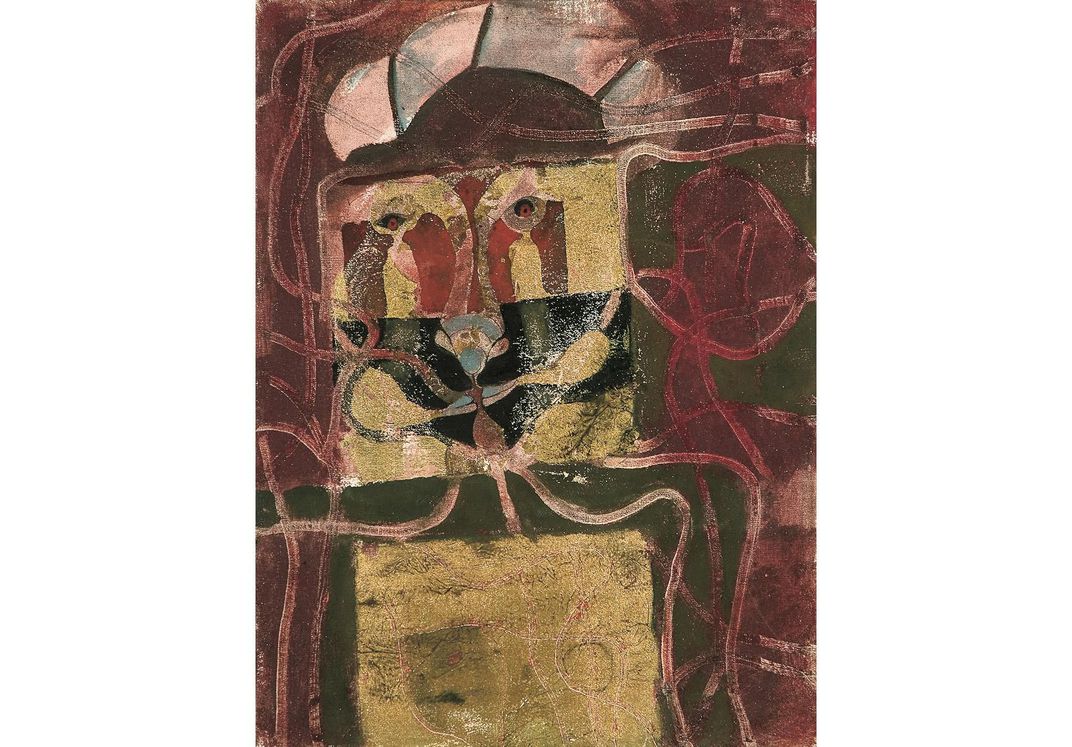

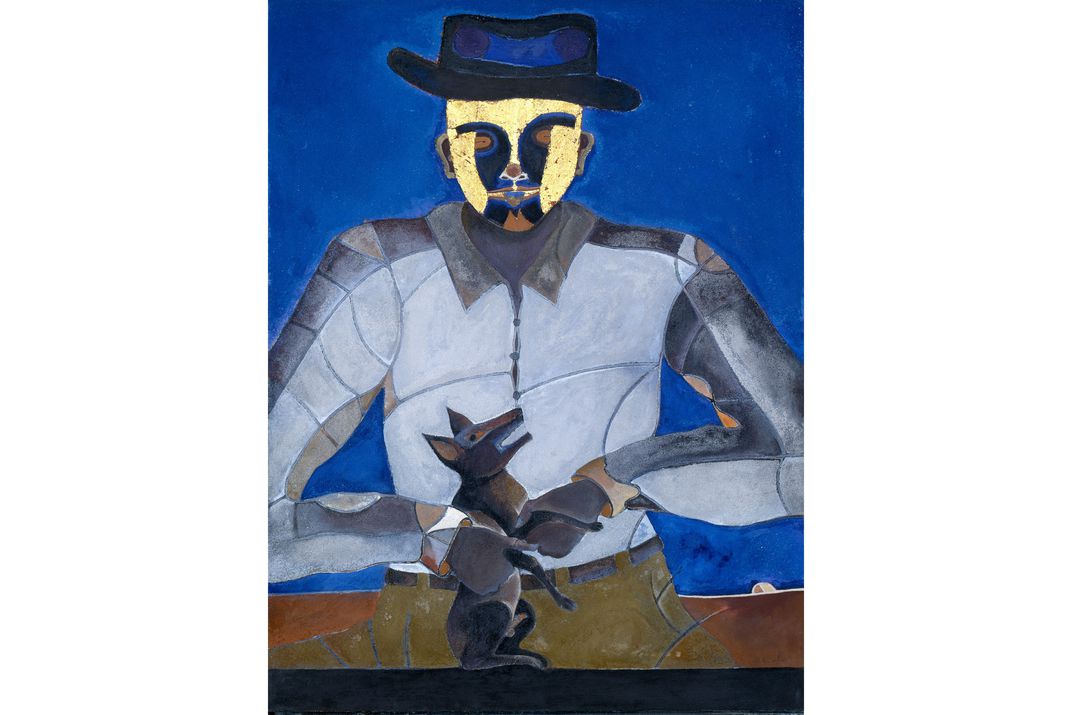

He remains a fully engaged artist, expanding a protean output—there are around 9,000 documented works—that defines a titan spanning 20th- and 21st-century art. “Toledo has no limitations,” says William Sheehy, director of the Latin American Masters gallery in Los Angeles, who first encountered the artist’s work 40 years ago. The real comparison, he adds, is “with Picasso.”

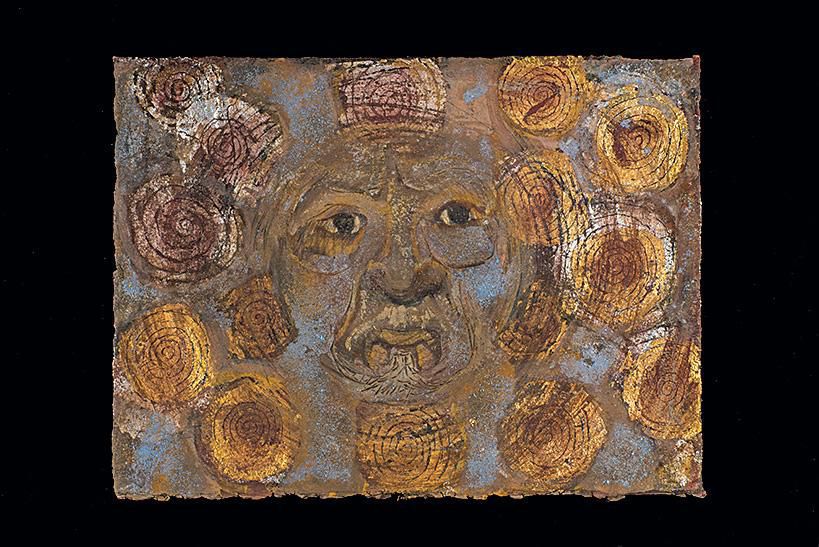

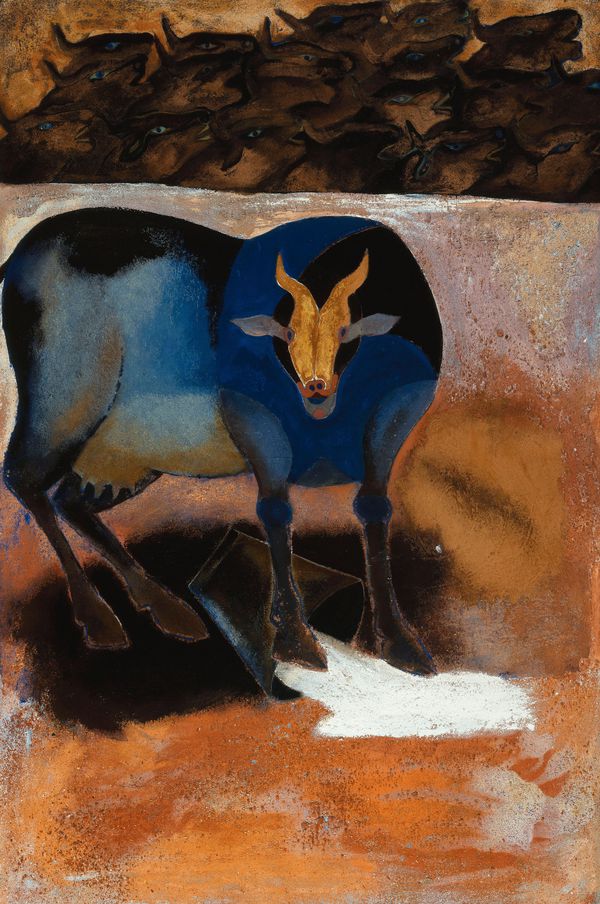

Mingling influences from Goya to Klee with his roots in the fabulism and folk traditions of Oaxaca, Toledo’s work bears the stamp of a galvanic life force. “He has transposed his observations into a language of his own,” says Sheehy, “fusing the human and natural worlds of his childhood—it’s all about connectivity.”

Yet he has not ceased to protest—these days the abuses of trade agreements, especially the prospect of U.S. companies introducing genetically modified corn into Mexico and thus undermining the integrity of age-old strains of native corn. One of his protest posters shows Mexico’s revered 19th-century reformer, Benito Juárez, sleeping on eight or ten ears of corn and above him “Despierta Benito!” (“Wake Up Benito!”) and “Y di no al maíz transgénico!” (“And reject genetically modified maize!”).

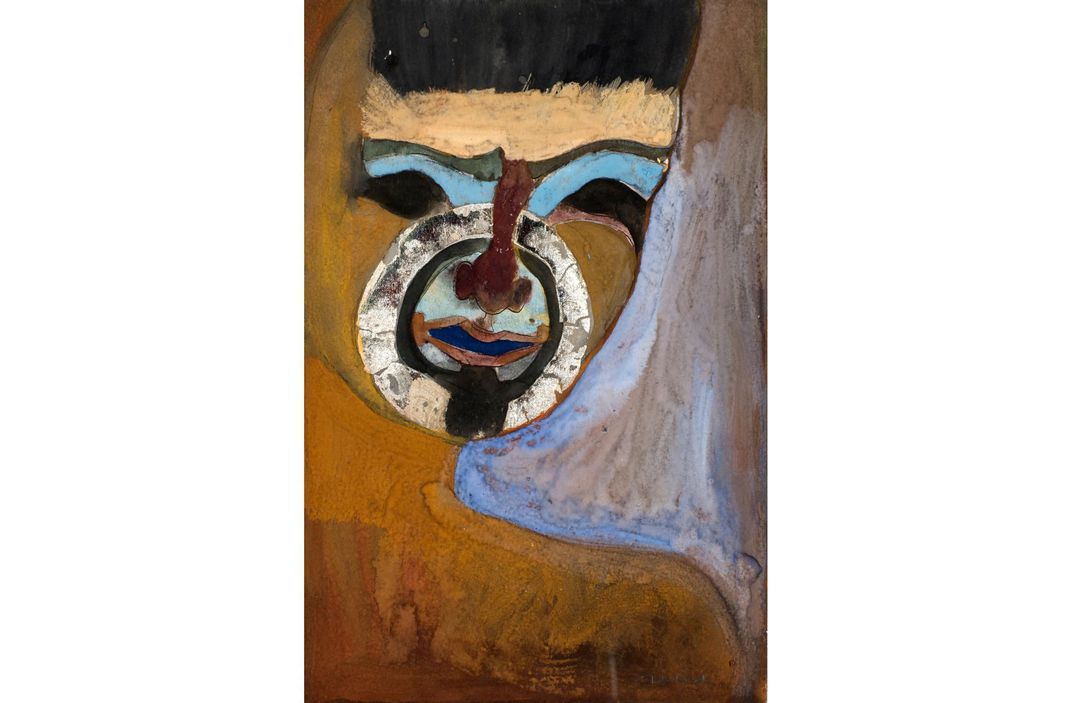

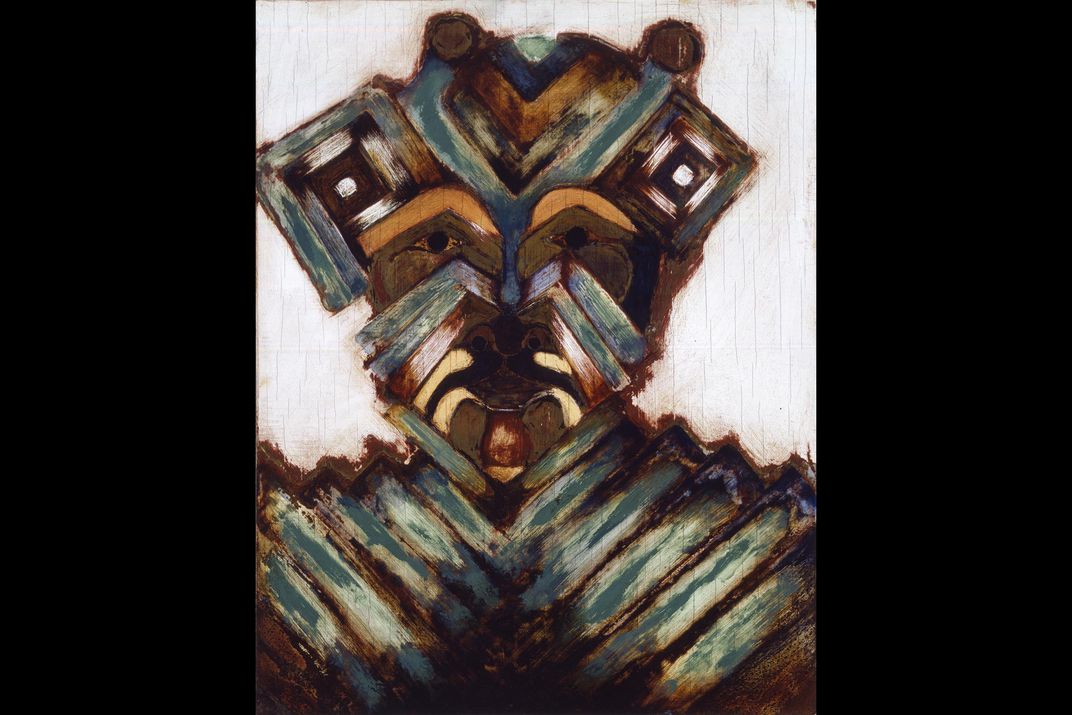

These preoccupations give some indication of Toledo’s passion. From the age of 9, when he was singled out in his school for his exceptional drawing ability (the picture happened to be a portrait of Juárez), Toledo has worked almost without a break, that is, 70 years—he turns 79 this July. He works in every conceivable medium—oil, watercolor, ink, metal; he makes cloth puppets, lithographs, tapestries, ceramics, mosaics and much more. He may produce a canvas depicting a vintage sewing machine, fragmented into Cubist-inspired components; create a ceramic of a mysterious bovine morphing into a kind of Minotaur; or paint a rushing river glistening with gold leaf and roiling with skulls.

(Galería Juan Martín. Photo: Archiva Graciela Toledo, Private Collection)

Though his paintings and sculptures sell all over the world for fabulous prices, he has not enriched himself. He lives simply, with his wife, Trine Ellitsgaard Lopez, an accomplished weaver, in a traditional house in the middle of Oaxaca, and has used his considerable profits to found art centers and museums, an ethnobotanical garden and at least three libraries.

IAGO is one of a number of cultural institutions that Toledo had founded—the Instituto de Artes Gráficas, a graphic arts museum and library housed in a colonial building across from Oaxaca’s famed Santo Domingo Church, dating back to 1571. A contemporary art museum, MACO, is another, along with a photographic archive (Toledo is also a distinguished photographer), a rare book library, a shop that made handmade paper for his prints, an environmental and cultural protection nonprofit organization. One library devoted solely for the use of the blind, with books in Braille, is named Biblioteca Borges, after the blind Argentine writer.

Most of these institutions charge no admission. Toledo believes that anyone who wishes should be allowed to enter these places and enlighten themselves, free. A country boy himself, he hopes that people from small villages, who might be intimidated by museums and forbidding public institutions, will visit and look at art produced locally.

* * *

Sara promised to help arrange the meeting. She was tall, half-Danish, preparing me for the visit, explaining that her father had not been well. She said that it was in my favor that her father knew that 18 of my books, both in Spanish and English, were on the shelves of IAGO.

Another reason for my seeing Toledo was that he was less than a year older than I. As the years have passed I have nurtured a special feeling for anyone close to my age. It means that we grew up in the same world, in the austere aftermath of World War II, that we knew the same terrors and tyrants and heroes, as well as the same cultural touchstones, certain books, certain fashions, items of slang, the music of the ’50s. We were in our early 20s in the tumble and conflict of the ’60s, witnessed the civil rights struggle, nuclear testing, Vietnam, the women’s movement and, distrustful of the received wisdom of the past, we discovered new ways of looking at ourselves and the world. We were hopeful, seeing oppressive institutions shaken up, and decolonization in Africa. We had lived through an era when authority was challenged by some activists like us, from the margins of society.

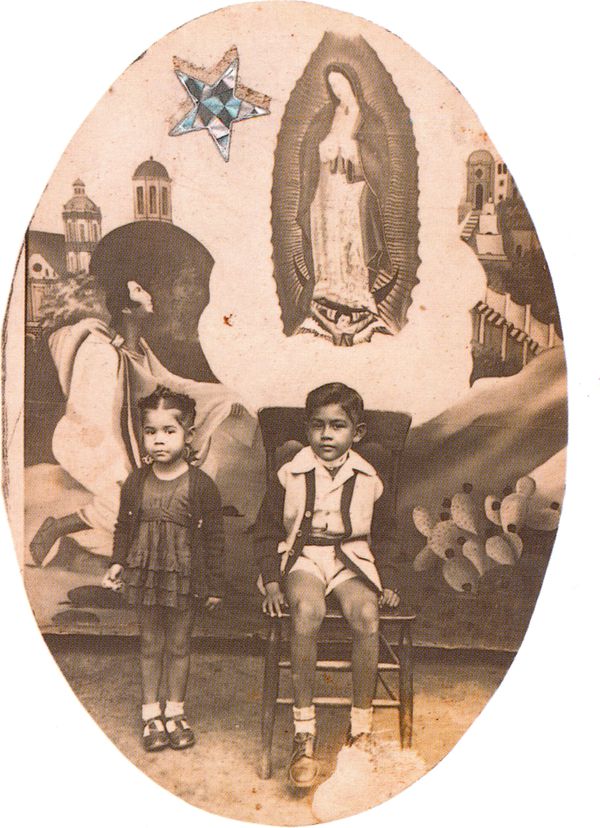

(Courtesy Francisco Toledo)

Toledo, whose origins were obscure and inauspicious, was the son of a leatherworker—shoemaker and tanner. He was born in Mexico City, but the family soon after moved to their ancestral village near Juchitán de Zaragoza in the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, nearer to Guatemala than to Mexico City—and being ethnically Zapotec, nearer culturally to the ancient pieties of the hinterland too. Though widely traveled (“Actually we grew up in exile”), he claims Juchitán as his home, saying, “You’re from where you feel you’re from.” The Toledo family kept moving, finally settling in Minatitlán near Veracruz, where his father set himself up as a shopkeeper.

Toledo was a dreamy child, much influenced by Zapotec myths and legends, and the wildlife and flora of a rural upbringing—elements that emerged in his art to the extent that he has become one of the greatest interpreters of Mexican mythologies. His work is filled with the many Zapotec deities, the bat god, the gods of rain and fire, and the sacred animals—rabbits, coyotes, jaguars, deer and turtles that make much of his work a magical bestiary.

(Private collection. Photo: © Christie’s Images / Bridgeman Images)

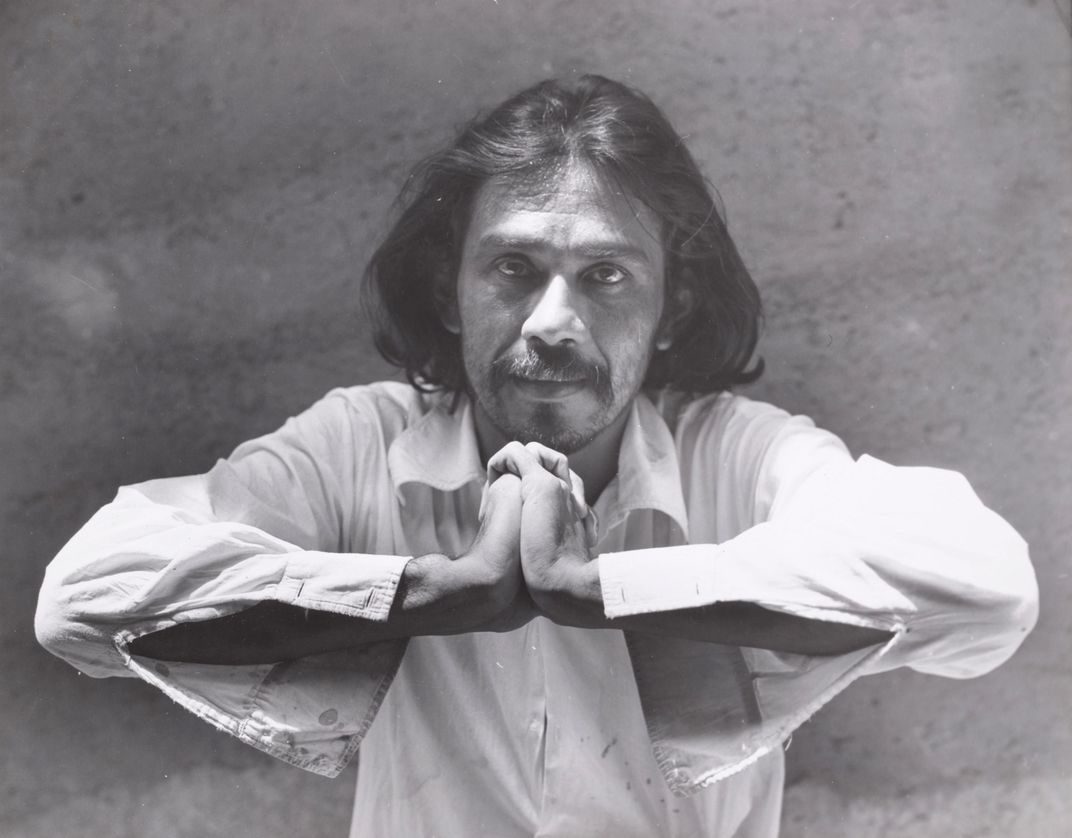

Recognizing young Francisco’s talent, his parents sent him to Mexico City to study the techniques of graphic art at the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes. He was just 17, but even so he was singled out by critics and connoisseurs for his brilliance and held his first solo exhibitions two years later, in Mexico City and in Fort Worth, Texas. Restless and now solvent, ambitious to know more, but still young—barely 20—he went to Paris, to continue painting, sculpting and printmaking.

In Paris he was mentored by another Mexican expatriate, and fellow Zapotec, Rufino Tamayo, and later worked in the atelier of the English expatriate printmaker Stanley Hayter, learning copper engraving. After Toledo’s first Paris show, in 1936, the influential French novelist and art critic André Pieyre de Mandiargues wrote, “The great and very pleasant surprise that we had in our first encounter with this Zapotec Indian was that of finally discovering a sort of genius in the arts, comparable in some ways to ‘the divine facility’ of certain masters….” And he went on, “I know of no other modern artist who is so naturally penetrated with a sacred conception of the universe and a sacred sense of life.” This was a vital endorsement, because Mexican writers and painters seldom gain recognition at home until they’ve been praised abroad.

Nostalgic less for the big world of Mexico than his remote ancestral pueblo, Toledo abandoned Europe and returned home in 1965—first a spell in Juchitán determined to promote and protect the arts and crafts in his native state of Oaxaca (he designed tapestries with the village craftsmen of Teotitlán del Valle), and then moving to Oaxaca City, where he helped create a cultural awakening, with his indignation and his art. Though he returned to Paris later for a period, and lived and worked in the 1980s in New York City and elsewhere, Oaxaca remains his home.

“He works all the time,” Sara told me. “He’s still painting. He’s multitasking. He makes fences of iron—well, they look like fences. They’re sculptures. He works with all sorts of material—felt, carpets, tiles, ceramics, glass, laser cutouts. He makes toys, he makes felt hats for little kids.”

(Photo: Angela Caparroso / Galería Arvil)

The earthquake that had destroyed parts of Mexico City in September 2017 also laid waste to an enormous section of the city of Juchitán, and moved him to action again.

“We formed a group called Amigos del IAGO and set up 45 soup kitchens in and around the city of Juchitán, and in other parts of the isthmus,” Sara said. “We were feeding 5,000 people a day for four months, until people got back on their feet.”

And she explained that the soup kitchens were not an entirely outside effort—a charity, doing everything—but rather a cooperative system, mostly operated by the Juchitán people themselves, with finance from Toledo. “Having something to do was therapeutic for them,” Sara said. “It took their mind off the earthquake.”

Not long after this chat with her, she gave me the word: I could meet Toledo at the arts center, where a show of his work was being mounted.

* * *

I arrived early enough to have a brisk walk-through of the new show and was dazzled by the variety of works—iron sculptures hung flat against the wall like trellises of metal filigree, posters with denunciations in large letters, hand puppets, hats, lithographs of mottoes, dolls in Zapotec dresses, a felt corncob labeled Monsanto, with a skull on it, and serene ink drawings—a large one completely covered with a shoal of beautifully rendered darting shrimp, flashing to one edge of the paper.

“Hola!” I heard, and looked up from the drawing of the darting shrimp and saw Toledo walking toward me.

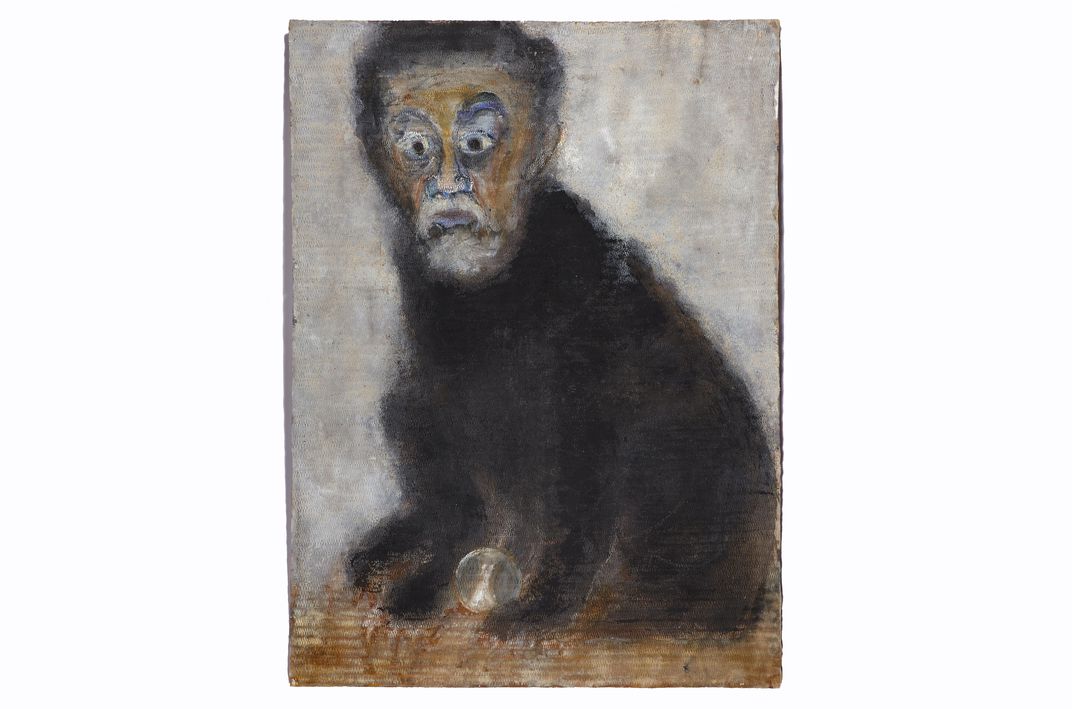

The first thing, the most obvious aspect of the man, was his head—a large, imposing head, familiar to anyone who knows his work, because Toledo has painted hundreds of self-portraits. With an intense gaze, accentuated by a tangled nest of wild hair, the head is much too big for his slender body, the slight torso, thin arms, skinny legs, looking doll-like and improbable. He seemed cautious and subdued, but courtly, austerely polite in the manner of old-fashioned Mexicans. I also felt at once, seeing his crooked smile, and the way he bounced when he walked, that he had too much heart and humor to make himself unapproachable. Some people—Toledo is one—are so naturally generous they have a justifiable fear of the clutches of strangers.

(Alfredo Estrella / AFP / Getty Images)

“This is lovely,” I said, of the drawing.

“Camarones,” he said, and tapped the glass of the case it lay in, shimmering with life and movement. “I like the way they swim together. You see the pattern?” And as though this explained everything, he added, “Juchitán is near the sea.”

He signaled to his daughter and made a sign with his fingers that indicated coffee drinking.

He became animated, smiling, as we walked around the exhibition. At the “Despierta Benito!” protest poster, he said, “This is against the government.”

A lithograph under glass was a copy of a 17th-century Spanish manuscript listing a Zapotec vocabulary, for the use of missionaries and officials. Another was also based on an old document, but one with images of men and women, their legs and hands in shackles and chains, titled De la Esclavitud (Of Slavery). His collages were arresting and multilayered.

“This is me,” he said of a mass of feathers, “Autorretrato en Plumas,” which when I concentrated I discerned was Toledo’s face picked out in gray feathers, glued to a board, a startling likeness. He laughed as I examined it, a meticulous pattern of pinfeathers. Nearby were some vivid photographs.

“I wanted to be a photographer from the age of 13,” he said. “I saw the Family of Man photographs in a catalog in Oaxaca. It opened my eyes! I bought a small camera. Around that time I went to Oaxaca to school. I thought, ‘Maybe I’ll be a photographer.’ I still take pictures.”

“But you drew from an early age, too?”

“Yes, I drew in school. I was 9 or 10. We saw the images of Orozco and Rivera. I liked to make drawings on the walls. My mother didn’t like it, but my father resisted her! And in Oaxaca I discovered a school of fine arts near La Soledad”—Basílica de la Soledad—“The library had books with William Blake images. I loved them, even though I couldn’t read the poems.”

“When my father said, ‘Go to Mexico City,’ I had to start all over again. I was 17 or 18 years old. I was at a school with an art workshop, in the Taller Libre de Grabado [a subsidiary of the National Institute of Fine Arts]. I chose to learn lithography, and I painted at home. But my school had many workshops—weaving, mosaics, murals, furniture, ceramics. I saw that there were so many ways to make art. I lived with a family that took care of me. The sister of that woman was married to a painter. She said, ‘I have a man here who chooses his food by the colors. If he doesn’t like the colors he doesn’t like the food.’”

Toledo paused and smiled at the memory.

“So that man took an interest in me and my work, and introduced me to Antonio Souza, owner of a very famous gallery. Souza let me use his home as a studio. He gave me my first show in 1959—I was 19, and the show went to the States.”

What sort of work was in this first show, I wondered.

“Little paintings—watercolors, of animals and people,” Toledo said. “All my life I’ve painted the same things.”

This simple statement is provable. On one of the shelves at IAGO are four thick volumes (published recently by Citibanamex) cataloging significant Toledo pieces from 1957 to 2017, in more than 2,000 pages, and demonstrating the consistency of his vision and the grace notes of his humor.

Souza told him that he needed to get out of Mexico and see the museums of Europe. “I went to Paris. I went to Rome. The Etruscan Museum in Rome—I visited it many times. In Paris I saw Waiting for Godot, when it was first produced, and all the time I was painting.”

His paintings became sought after for their singular beauty. His work resisted all classification and fashion. He was not attached to any movement, even when the art world was turbulent with abstraction and Minimalism and Color Field and Op Art. He elaborated his ancestral visions of masks and folk tales, haunted and highly colored landscapes, and eroticism that was both comic and gothic. “He intuits the timelessness of authenticity,” the Guatemalan art critic Luis Cardoza y Aragón wrote. In 1967, an enthusiastic Henry Miller—himself a watercolorist—wrote the text for a Toledo exhibition.

“Toledo has created a new visual grammar,” the Mexican writer Juan Villoro told me, when I asked him to assess Toledo’s uniqueness. “His colorful reality is a setting for fables where human beings are accidental witnesses of the real rulers of the world. Grasshoppers and iguanas, coyotes and deer, scorpions and frogs are the masters of that universe. But they don’t live in comfort or in the perfect boredom of paradise. Toledo’s ‘Garden of Earthly Delights’ is a world of troubles, passions, sexual attractions between different and sometimes opposed species. His nature is an enhanced version of the original model. His dreams are not a departure from reality: They are an extreme enhancement of the real.”

Toledo and I were still walking through his new show. Here was a woodcut of two rhinos copulating; in a decorated frame, a cracked mirror (“The sister of Snow White,” Toledo said); the wheel of a spider web spun out of steel wires. Then we came to a portrait of Albrecht Dürer, his hair and beard rendered by Toledo with human hair.

“Dürer was fascinated by hair,” Toledo said simply. Dürer was one of his heroes, he said. I asked which others he admired. Rufino, of course, “and many others.” Then he remembered. “Lucian Freud—very good.”

(Miguel Tovar / Latin Content / Getty Images)

We came to a large work, of many faces, individual portraits of the 43 students who had been abducted and killed at Ayotzinapa, the faces printed in melancholy tints, like Russian icons, very different from the faces on the “Ayotzinapa Kites.”

“Sad,” Toledo said. “A tragedy.” He steered me out of the exhibit to a small table, where two cups of coffee had been placed, along with a pile of my books. “Sit—please. You can sign them? For our library.”

I signed the books, and thanked him for meeting me at short notice. I told him he was the only person in Oaxaca I had wished to meet, and when I said this was not simple adulación, he dismissed it with a wave of his hand.

“My English is no good.”

“It’s perfect.”

“I’m old, I forget,” he said. “I’m going to stop painting sometime.”

“Please don’t say you’re old,” I said in Spanish. “Because I’m the same age.” And using the Mexican expression for an older person, “We are men of judgment.”

“Maybe. I like to think so,” he said in English.

“I’m interested that you went to Paris when you were very young,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “But in Paris I was alone, and lonely. I worked, I did painting and prints. Tamayo was kind to me. I felt less lonely with him.”

The renowned Mexican painter Rufino Tamayo had gone to Paris in 1949—fled, perhaps, because he found himself out of sympathy with the passionately political muralists such as Rivera and Orozco, and he was skeptical of revolutionary solutions. Tamayo, wishing to go his own way, took up residence in New York City, and after the war worked in Paris. He encouraged Toledo to paint in his studio, and though Tamayo was 40 years older than Toledo, they had much in common, proud of their Zapotec ethnicity, both resisting classification, making art in prints, in painting, in sculpture; and in the end, Tamayo returned to Oaxaca, like Toledo.

(© Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona Foundation / Art Resource, NY / Artists Rights Society, NY)

“I came back to be among my own people and my family,” Toledo told me. “I wanted to speak Zapoteco again, in Juchitán.”

“So you were happy then?”

“No. I couldn’t work there,” he said. “It was the noise, too much activity. I liked the place—I was home. I could speak Zapoteco—my grandfather and father and others spoke it. I don’t speak it well—I understand it. But I wanted to paint, so I left.”

“Did you miss Paris?”

He cocked his considerable head. He said, “In Paris I fell in love with a woman. She was Vietnamese. I had an idea. I planned to go to Vietnam with her—this was 1964, when it was very bad there.”

“What was your idea in going to Vietnam in wartime?”

“Just to see it,” he said. “I thought I could teach drawing in classes to American soldiers. And I could meet the girl’s parents.” He shrugged. “But the girl’s parents would not support my application for a visa. So in the end I left Paris. I went to New York City, but I was lonely there too.”

I mentioned my feeling of meeting someone my own age, how we had both lived through the events of the 1960s—Vietnam, demonstrations, political and social upheaval. He had experienced at close hand the massacre of students in 1968 in Mexico City and was so outraged by it he removed his paintings from a government-sponsored exhibition shortly after, destroyed some of them and sold others, giving the money to the families of the murdered students.

“You’re my age—but you’re strong,” he said. He clapped me on the shoulder. “Driving your car in Mexico!”

“But I’m sure you drive.”

“My wife drives—but me,” he tapped his chest regretfully. “My heart.”

“What happened to the Vietnamese woman?”

“Funny thing. She married a G.I. and went to live in California,” he said. “Now she’s a widow, and old, but I still talk to her. She comes to Oaxaca—I see her here, we are friends.” He became restless, adjusting his posture on the chair, holding the coffee cup but not drinking. He said, “Have you seen what is happening in Mexico?”

“I’ve traveled a little bit—driving around. I drove from the border, stopping in towns and talking to people. I stayed a while in Mexico City. I’m trying to make sense of Mexico.”

“Good for you, amigo!” But he said he didn’t travel, and he gave me his reasons. “Roads are dangerous. Planes are dangerous. I don’t like airports. I don’t like the colors of the insides of planes. I don’t like the smells.”

We talked about Mexico City. He told me of his studies there, and the artists he’d met. I asked him what he thought of Frida Kahlo, because as a budding artist he would have known her work when she was at the center of attention, as an artist, as a public figure, iconic, adored or disputed over—she died in 1954.

“I started out hating her,” he said. “Then I later began to see that she represented something. And outsiders were interested in her. Her life was so complex and painful. So she is something,” he said. Then as an afterthought, “But there are so many others!”

To change the subject, and suggest a place I’d been, I clicked on my phone and showed him a photograph I’d taken of a tiny peasant woman in a remote mountain village in the Mixteca Alta.

Toledo peered at the photo and frowned. “She’s poor,” he said. “Nothing will happen to her. No one cares about her, or people like her. No one cares about the poor, or about their lives. The government doesn’t care.”

He brooded a bit and sipped his coffee.

“Mexico is in a bad time now,” he said. “It’s not just the U.S. and Trump. It’s other things. Drugs and gangs, and the immigration from Central America.” He gestured, spreading his thin arms, his delicate fingers. “Oaxaca is in the middle of it all.”

This virile and humorous man, full of life, full of ideas and projects, is an optimist in action and in his art, but a skeptic in thought. He fully acknowledges the human impulse toward self-destruction.

“But you’re working,” I said. “That’s the important thing. Tamayo worked until he was 90.”

“He was strong. I’m not,” he said. “My studio is here, I’m still painting. I look at the paintings I’ve done and I’m not that satisfied. I’ve done so many! I want to move on and do other things.”

He got up and led me back into the exhibit, past the metal sculpture and the felt hats, the light box of transparencies of a human body, pull-toys, and laser cuts of insects, including a large black scorpion.

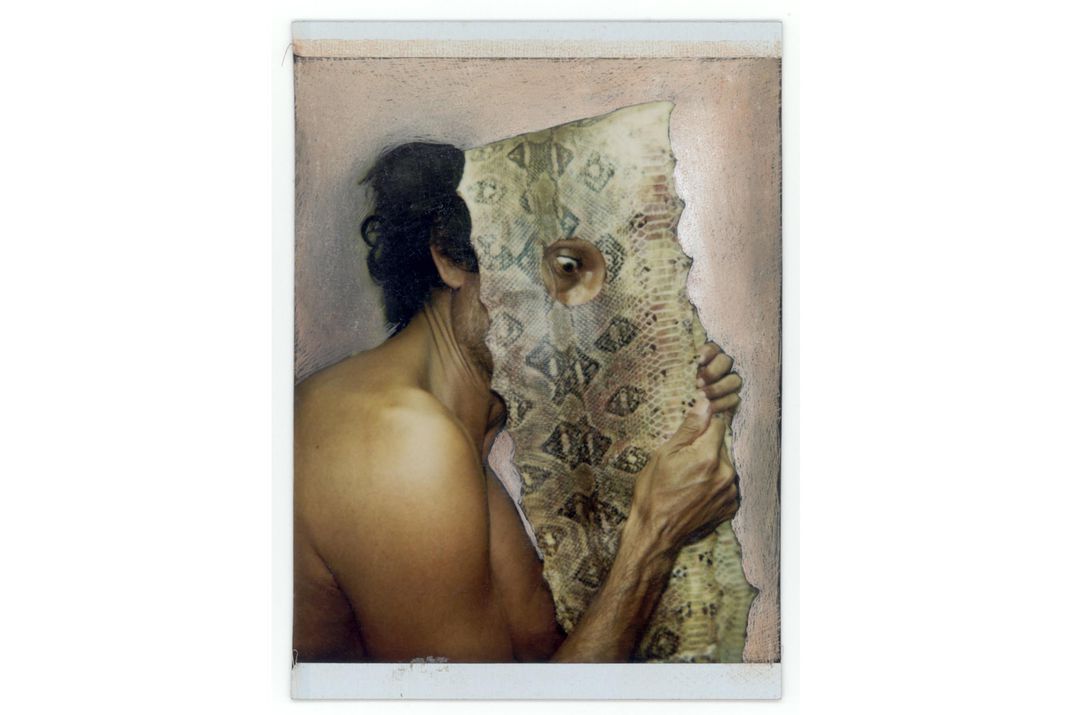

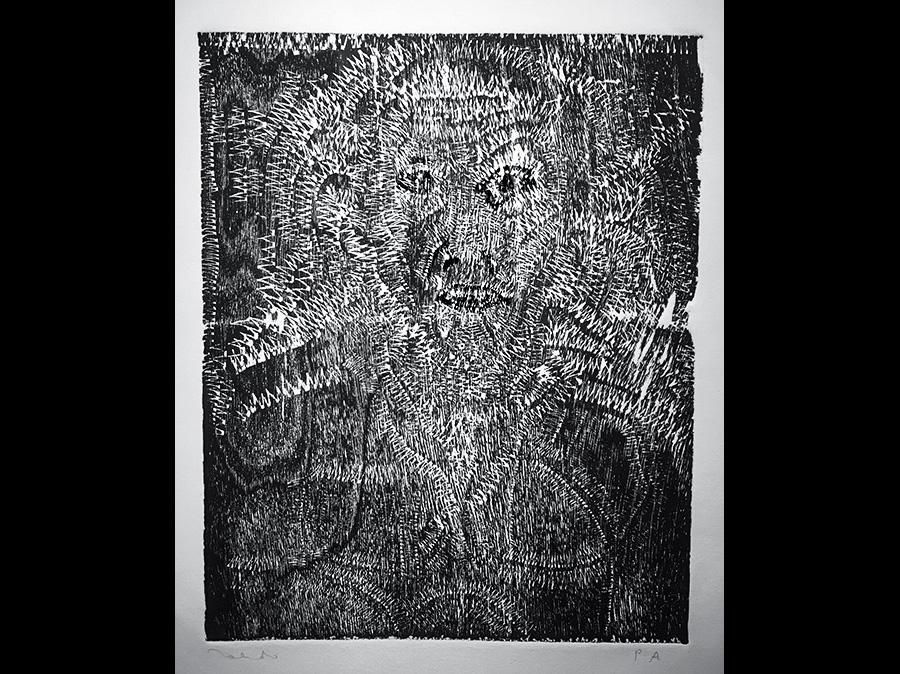

“Right now, I am doing self-portraits. I started doing self-portraits first when I had no money. But I had a mirror! I couldn’t do nudes. They said, ‘You’re too young.’ I made a self-portrait yesterday—not one, many. I make ten or more at a time.”

In one show not long ago, titled, “Yo Mismo/I Myself” there were more than 100 self-portraits, all of them striking, some of them severe, others self-mocking, the greater number depict a man with anxious and disturbed features.

“Did you work today?”

“I work every day.”

“What did you paint today?”

“Recently some people in Mérida asked me to do some pictures of pyramids. I’ve been doing that, lots of them.”

He opened a chest in which booklets were piled. I took them to be children’s books, but he explained that they were stories he had illustrated.

“I’m a publisher, too,” he said. “I published these—I want to publish more.”

I picked up a few and leafed through them, and was impressed by the care with which they had been printed: lovely designs, beautiful typefaces, glowing illustrations—of fabulous animals, jungle foliage, witchlike faces with intimidating noses.

“Maybe you can write a story for me,” he said. “I’ll make a picture. I’ll publish it.”

“I’ll write one, as soon as I have an idea.”

“Good, good,” he said, and we shook hands. Then he hugged me, and in a whirl—his bouncing gait, his wild hair—he was gone.

Sometime after that a Mexican friend of mine, strolling in Oaxaca, saw Toledo hurrying to his library. He said hello and mentioned my visit.

“He’s a good gringo,” Toledo said. You can’t have higher praise than that in Mexico. But my friend had more to report. He texted his fiancée in Mexico City: “I just saw Toledo.”

“Pide un deseo,” she texted back. “Make a wish.” Because any encounter with this powerful man, or his work, was lucky, magical, an occasion to celebrate.

[ad_2]

Source link