ART NEWS

This Artist Imagines How Nature Evolves Following an Environmental Apocalypse | At the Smithsonian

[ad_1]

SMITHSONIAN.COM |

July 19, 2019, 11:46 a.m.

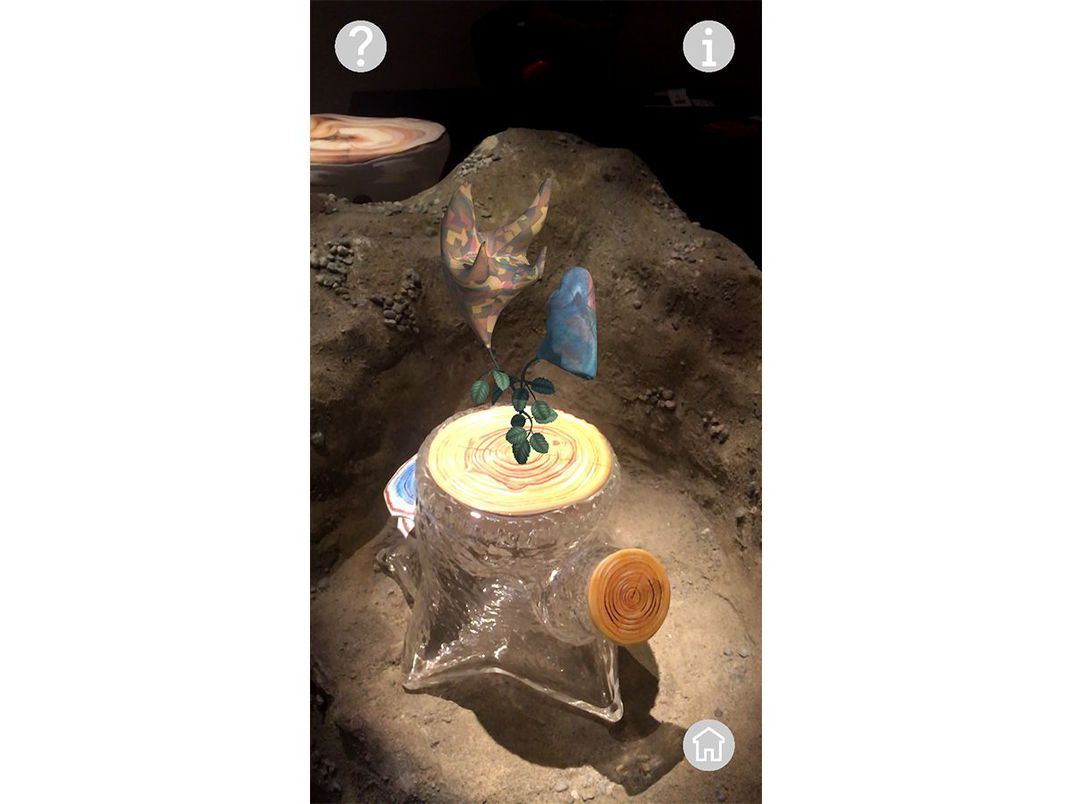

Walk into a first-floor room at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the high-ceilinged space looks, at first, quite desolate. Tree stumps made of glass sprout from five rock-like mounds, and at the center of the room, nestled in a sixth craggy habitat, stands a tree made of copper and glass. Otherwise, the landscape seems barren and nearly sapped of color.

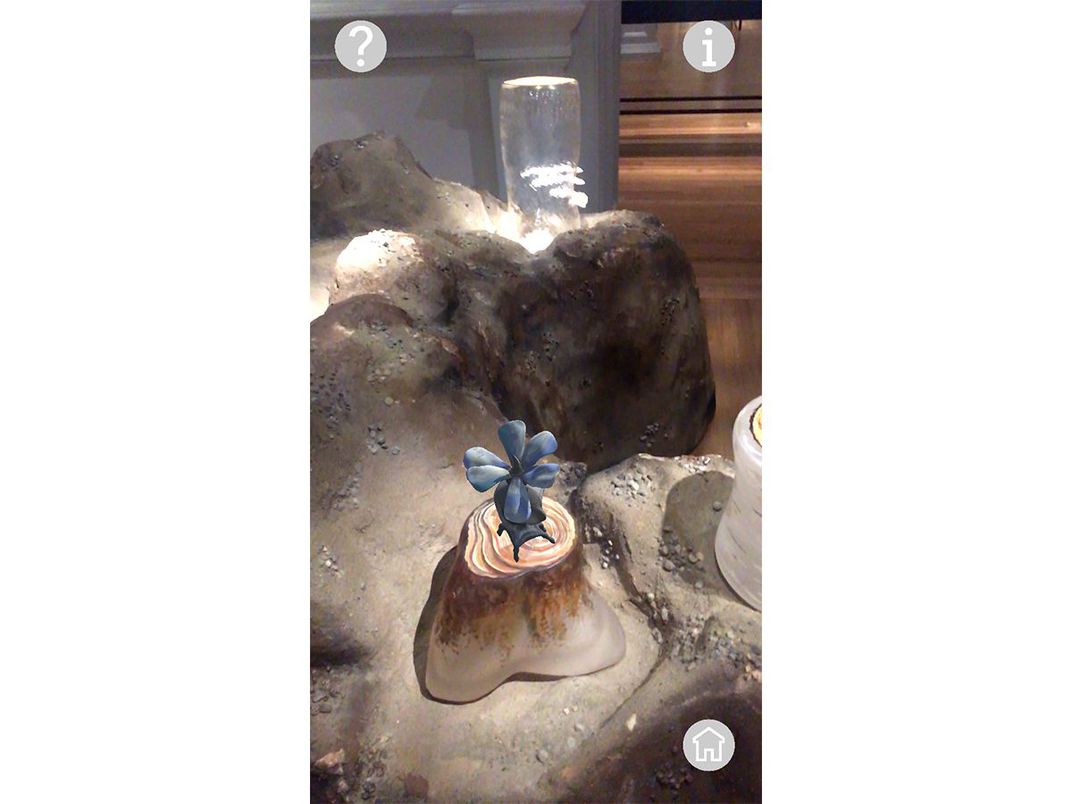

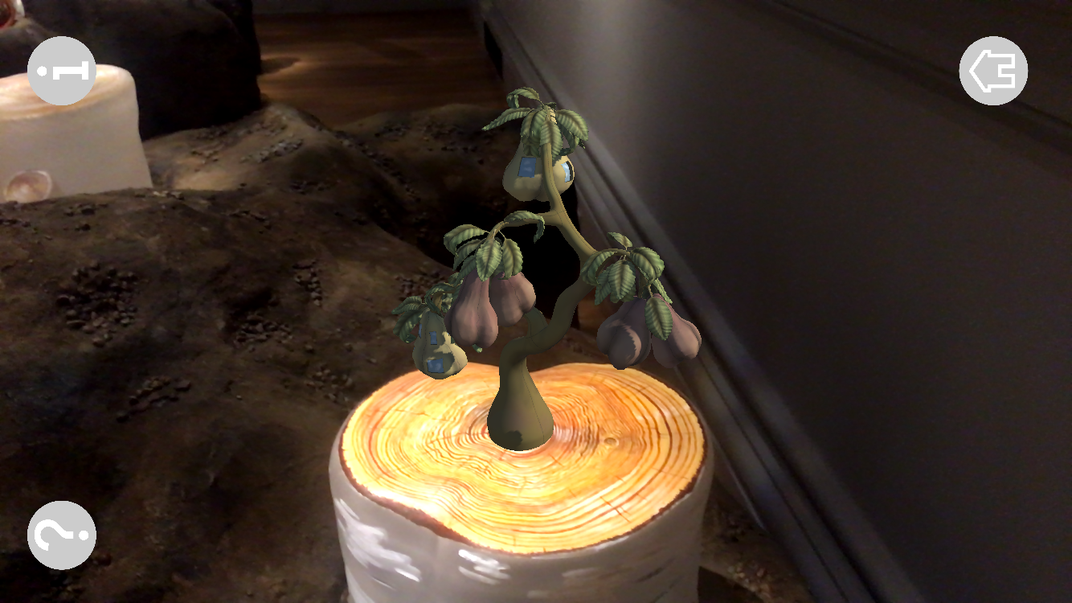

But grab one of the red-cased tablets off the wall or unlock a smartphone, and the exhibition springs to life with an augmented reality display. Aim the device’s camera at the tree rings, and inventive flora of the future appear, gently swaying in a virtual breeze. The exquisite world created in the museum’s new exhibition “Reforestation of the Imagination,” comes straight from the mind of the Seattle-based artist Ginny Ruffner, who decided to ponder the imponderable—in the aftermath of an apocalyptic mass extinction event, how might life on Earth continue to evolve and thrive?

“Reforestation of the Imagination” presents an optimistic answer to that question. “I prefer to think that the world will evolve more beautifully,” says Ruffner, an artist whose work invokes themes of nature and resilience. “Who knows what wonderful things might happen?”

(Courtesy of Ruffner Studio, photo by Ruffner Studio)

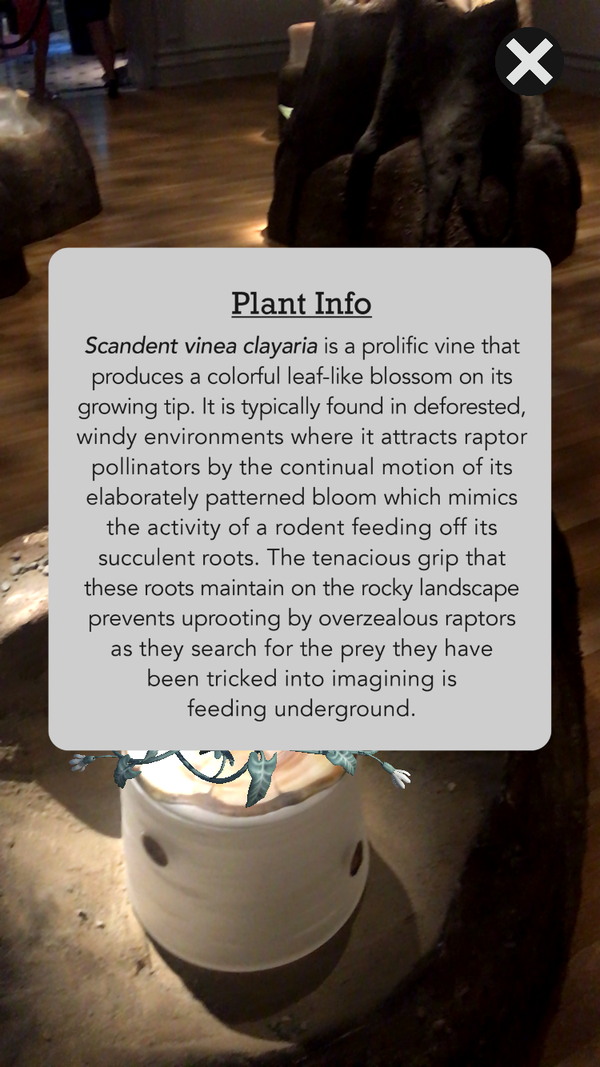

To see some of the “alternative evolution” possibilities the artist has crafted in her re-imagined world, visitors download the Reforestation app and focus the cell phone or tablet’s camera on one of the hand-painted glass tree trunks that dot the gallery. In the reimagined world, powder blue, scythe-like petals of the plant Ventus ingenero rotate in the wind blowing across the plant’s grassland plains habitat. The new species is described in an informational box that appears with the touch of a button. A total of 18 imaginary plants, some with spiraling vines or blue flowers that resemble toilet plungers, grow in Ruffner’s new world.

Fittingly, the evolution-focused exhibition is part of the Renwick’s own progression. Robyn Kennedy, the museum’s chief administrator, views “Reforestation of the Imagination” as a sequel, in part, to the museum’s highly popular and much-acclaimed interactive and experiential shows—last year’s “No Spectators: The Art of Burning Man” and the 2015 exhibition “Wonder.”

“We’re very conscious of moving into the 21st century,” says Kennedy, as the definition of craft art expands and includes new crossovers. For her part, Ruffner agrees that technology is expanding the possibilities for art: “I think that beauty itself is evolving,” she says.

(Reforestation app screenshot, Lila Thulin)

(Reforestation app screenshot, Lila Thulin)

(Reforestation app screenshot, Lila Thulin)

Ruffner, who grew up in the South, is known for her glass art as well as her public art projects, including a nearly 30-foot-tall flowerpot installation in downtown Seattle. The artist graduated with a M.F.A. from the University of Georgia and relocated in 1984 to Seattle to teach at the Dale Chihuly-founded Pilchuck Glass School. Seven years after that move, when Ruffner was 39, an automobile accident nearly took her life. In a 2011 TEDx talk, Ruffner told of how doctors warned that she might never wake from a coma, let alone walk or speak again. But after five weeks, she did wake up, and after five years in a wheelchair, Ruffner relearned how to walk. Her drawing hand, her left, had been paralyzed, so she now paints with her right.

In 2014, Ruffner visited a tech company on a friend’s suggestion. Learning about augmented reality in the years before apps like Pokémon Go familiarized the public with the technology was, in Ruffner’s telling, proved a creative catalyst. It opened, she says, a Pandora’s Box of possibilities.

Augmented reality allows a digital environment to be overlaid onto the real world. By contrast, virtual reality shuts out the real world to immerse the user in a digitally created universe. In Pokémon Go, the physical locations double as must-visit landmarks in the game’s virtual world. An AR tour of George Washington’s home, the popular Mount Vernon in Virginia, features virtual re-enactors and 3-D models. And the AR experience found in Google Glass, which, while short-lived on the general market, is now being used in manufacturing and may be able to help autistic children learn to recognize emotion.

But before she could create AR art, Ruffner had to school herself. “I didn’t know diddly-squat,” she laughs, adding, “I always love a good challenge.” The artist audited an augmented and virtual reality course at a local college, training herself to use the same software Pixar uses. She hired a classmate, digital designer Grant Kirkpatrick, as her tutor for the course, and the duo created AR projects, such as “Poetic Hybrids,” which allows the audience to collaborate on holographic sculptures.

It took the pair several years to take “Reforestation of the Imagination” from the germ of an idea to its final debut at Seattle’s MadArt Studio in early 2018. Activating AR from the glass tree stumps proved problematic. It would only be possible if they could make the surface flat, strip it of transparency and translucency, and add a high-contrast, unique pattern. Ruffner solved that conundrum, designing opaque white glass tree stumps that her glassblowing assistants crafted. Hand-painted tree rings cap off each stump. The ring pattern on the trees activates the app and in the viewfinder, the visitor finds the image of the corresponding AR plant.

(Courtesy MadArt, photo by James Harnois)

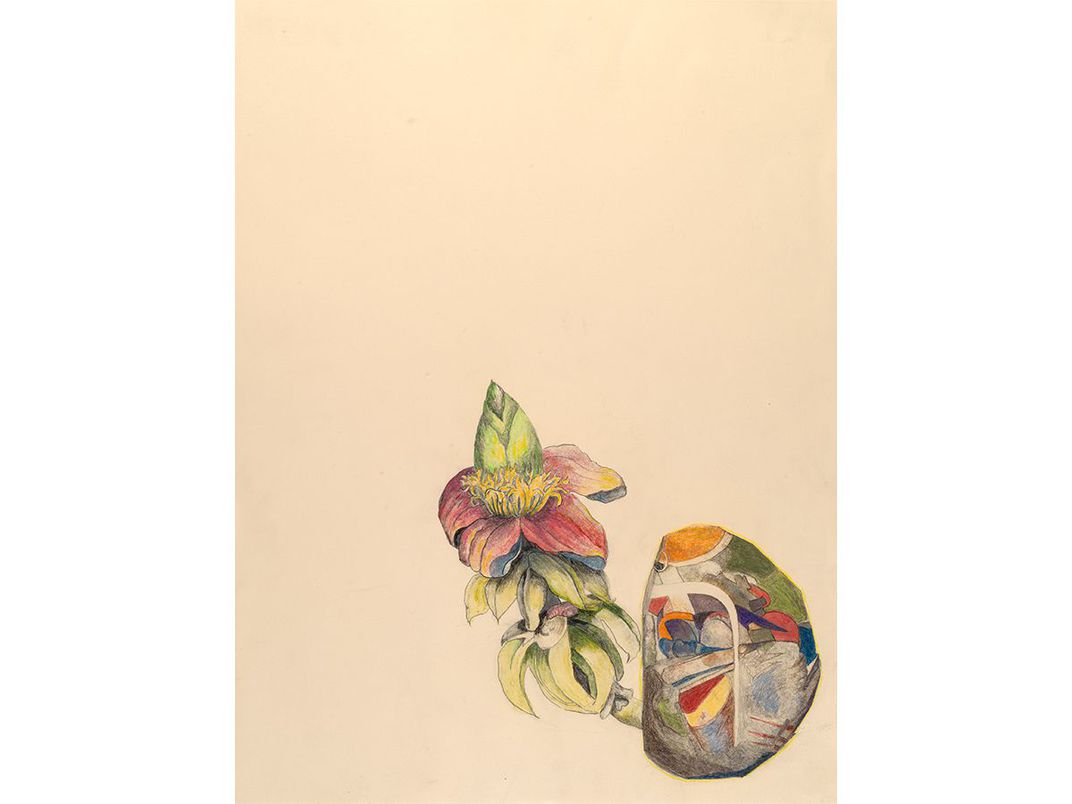

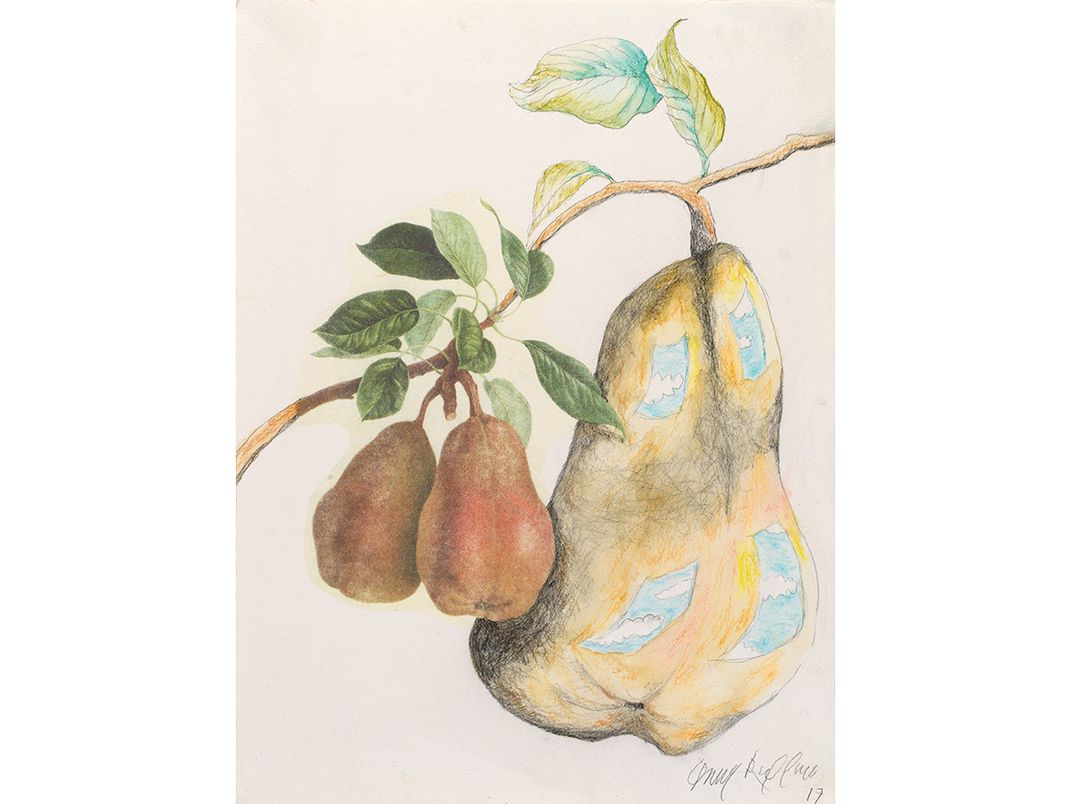

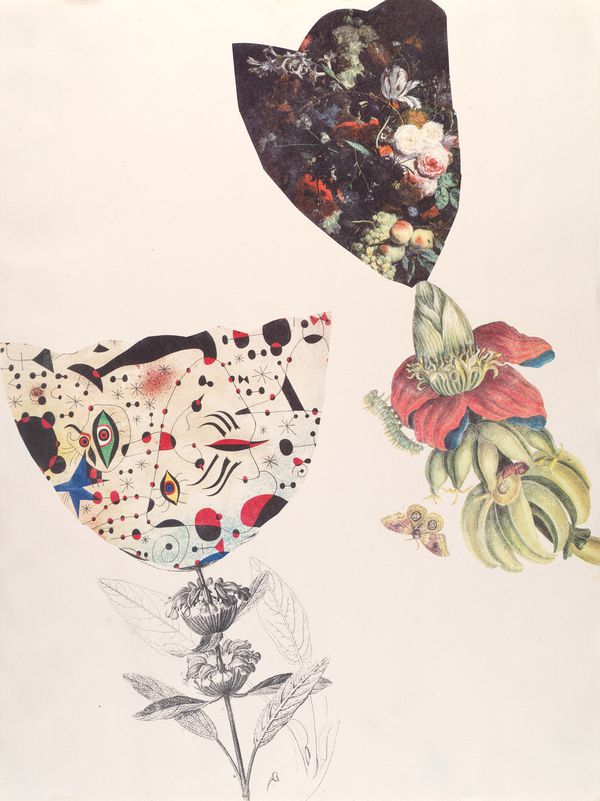

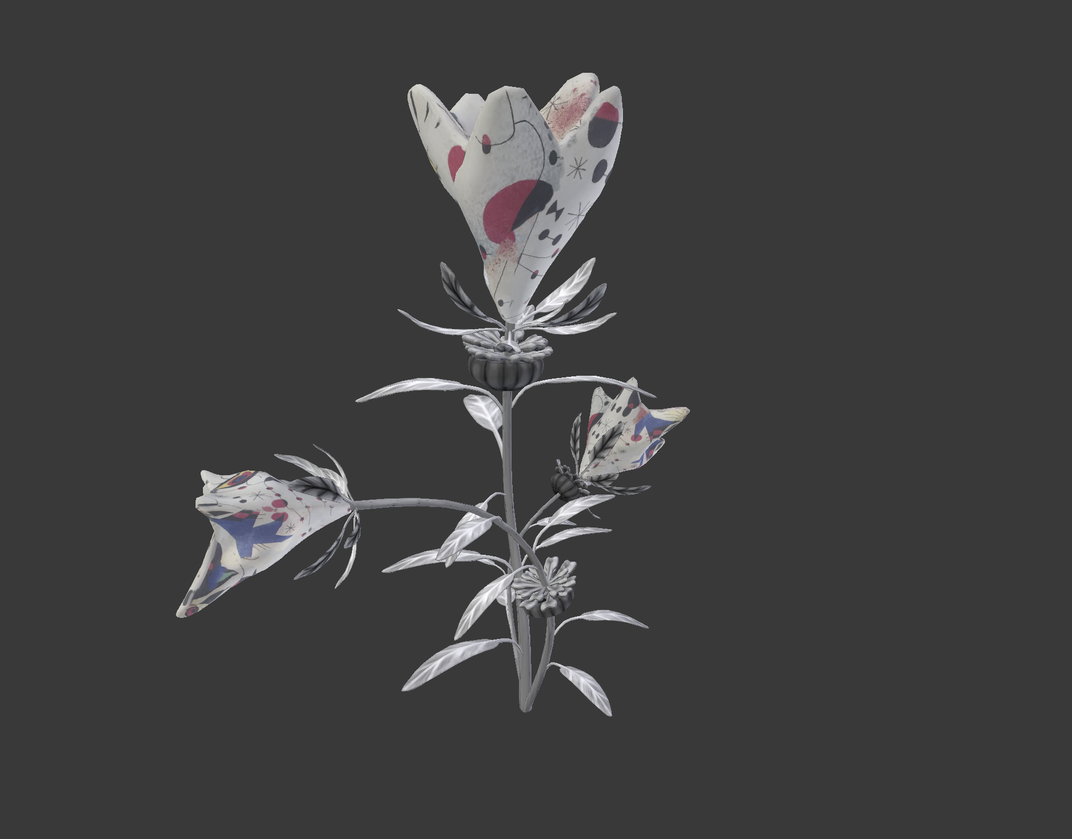

Ruffner wanted exhibition viewers to experience a landscape when they walked in the door—not just an empty room peppered with AR-activating codes. To create the land masses that house the tree stumps, she partnered with a company that manufactures natural history displays for museums. They built six rocky islands to display the tree trunks and the bronze-and-fiberglass tree. Ruffner conceptualized the plants through watercolor paintings, and Kirkpatrick brought digital life, turning those paintings into 3-D holograms. (Ruffner’s paintings hang on the walls of the gallery.)

(Collection of the artist, photo by Gene Young)

(Courtesy Ruffner Studio)

Finally, Ruffner, a gardening enthusiast, developed an imaginary taxonomy and backstory for each creation, looking up words in Latin to give them scientific names. Digitalis artherium counts among her favorites. The name is a wry art-world joke about a flower “formerly abundant in Manhattan,” whose dried, powdered petals possess hallucinogenic properties.

Ruffner doesn’t intend for the show to come off as preachy; rather, she’d like visitors to feel “hopeful and curious, two phrases I enjoy the most.” Yes, the exhibition initially shows a scene of environmental devastation that Ruffner describes as the result of climate change. The show doesn’t address the question of what happened to humans in the reimagined landscape, but through her digital flora, the artist says, “I just want to offer a not-so-bleak possibility.”

“Reforestation of the Imagination” will be on display at the Renwick Gallery of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, located on Pennsylvania Avenue at 17th Street, from June 28, 2019 until January 5, 2020.

[ad_2]

Source link