ART NEWS

The Last of the Great American Hobos | Arts & Culture

[ad_1]

There’s a kind of late summer Midwestern sunset, maybe you’ve seen one, so beautiful and so strange it’s dislocating. From end to end the whole sky goes rose pink, and a giant sun hovers out there like a live coal over the corn. For a while, nothing moves. Not that sun, not the moon, not the stars. Time stops. It’s dusk in farm country, coming up on twilight, but there’s something of eternity in it.

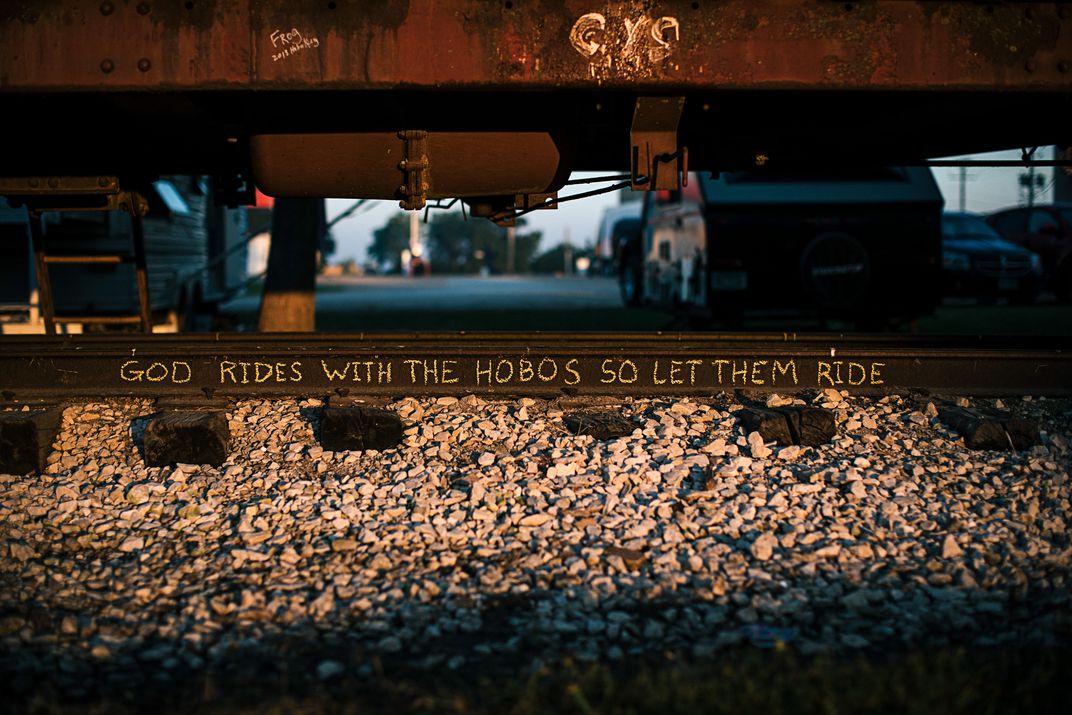

Not long ago out in Britt, Iowa, they were watching that big sun hang behind the grain elevators while the orange light from the campfire flickered up in the hobo jungle. This is by the railroad tracks off Diagonal Street, just over from the cemetery and a couple of blocks down Main Avenue from the center of town. And after dinner, once the pots and pans are washed and stacked, the hobos will sit and smoke and sing a few choruses of what sounds like “Hobo’s Lullaby.” Not far away, at the foot of the boxcar, in the Sinner’s Camp, they’ll tell stories and drink beer in the lengthening shadows.

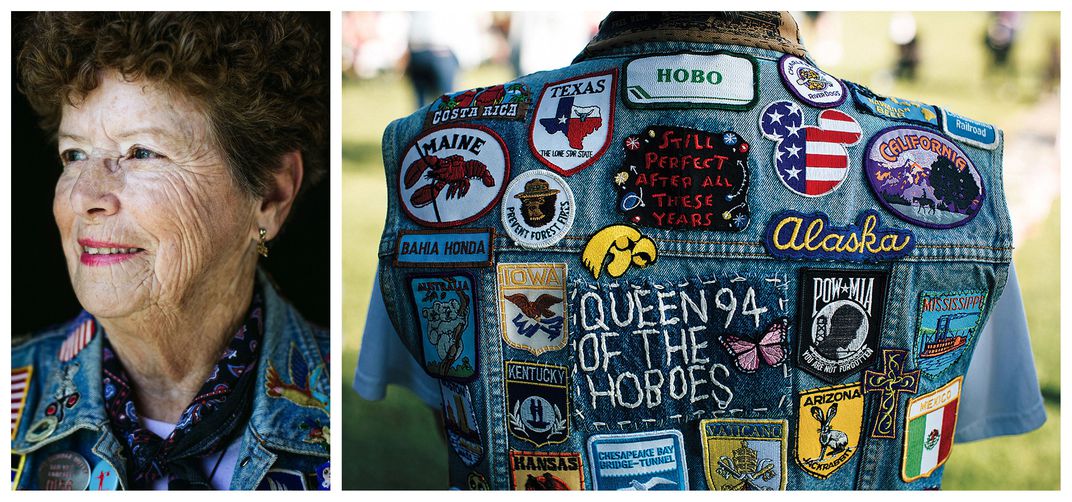

Maybe 50 hobos in the jungle this year, and an equal number of hobo hobbyists and hobo historians and hobos-at-heart. Connecticut Shorty and Jeff the Czech, Minnesota Jim and Mystic Will, Slim Tim and Jumpoff John, Sassy and Crash and Sunrise, Dutch and Half Track and IoWeGian, Tuck the King and Queen Minnesota Jewel, Gypsy Moon and 4 Winds and Honeypot Heather, Ricardo and K-Bar and New York Maggie Malone. Across from the boxcar are the outdoor kitchen and the equipment shed and the little pavilion with the picnic tables. The big fire sits at the center of it all, and the whole jungle, maybe an acre, is ringed by tents and cars and vans and little motor homes. Almost no one rides the freight to get here anymore. Way harder to catch out since 9/11 and harder still for an aging hopper. Jumping a train is still a dangerous act of sometimes desperate athleticism. Even in the firelight it’s an inventory of faded tattoos and gray ponytails, of vivid misremembrance and missing teeth, of crutches and sunburn and spotless denim, of balky hips and whiskey breath and nicotine stains. But there are children and grandchildren running around here, too, and a few young hobos, gutter punks and dirty kids, and tourists and fans and citizens. There’s even a group of students down from South Dakota State University. The whole place hums to life as day drains into darkness.

(Alyssa Schukar)

Every hobo has a moniker, a nickname grounded in habit or origin or appearance, like Redbird or Frisco Jack or Bookworm. Not every hobo wants to share his or her real name with the straights and the Square Johns, of which, with my notebook and recorder and wingtip shoes, I am decidedly one. (My hobo name is Seersucker. I wish I were kidding.) A few, the ones trying to outrun something, won’t even talk to me.

So monikers it is. As an editorial matter, know that I spoke to these folks and they spoke to me, that my bosses know what’s what and that these interviews were accurately recorded and transcribed, and that for the purposes of this story I respect every hobo’s right to anonymity.

In a society of citizen consumers, to have nothing, to own nothing, by choice, might be the most radical politics of all. And it’s worth mentioning here that not every homeless person is a hobo. And as the hobo fades from the American scene—except as a visual or literary cliché—there’s more and more confusion on the matter. A hobo is homeless by choice. Even then, not every hobo is completely homeless. Most these days have a semipermanent address somewhere for the winter. Especially the older hoppers.

Hobo slang can be intuitive, or impenetrable, but it’s always colorful. For example, the “jungle” is just the communal hobo camp, usually near the railroad yard. Your “bindle” is your bedroll. Your “poke” is your wallet. “Hundred on a plate” is a can of beans, and the jungle kitchen is run by the “Crumb Boss.” The “bulls” are the railroad police. “Flyers” and “hotshots” and “redballs” are all fast freights. “Catching out” means hopping the train. To die is to “catch the westbound.” And understand this, above all else: A “hobo” is an itinerant worker; someone who travels and finds work. A “tramp” travels, but mostly does not work. A “bum” neither travels nor works.

And of course the whole thing runs on talk, endless talk. Because talk’s free; because even if you give away everything you own, or they take away everything you have, you still have your stories. And every story here begins as the same story.

Why I left home.

I did a lot of hitchhiking right after high school. And one time my brother was out hitchhiking in California, and some tramps got a hold of him and told him ride the trains instead of hitchhiking, and so he rode trains. They came back, and that was in 1973. They were talking in a bar about riding out to see Evel Knievel jump the Snake River Canyon, and I started to listening to it, and I worked seasonal and stuff. I had some freedom there. I was in. And so my older brother….There was 11 of us gone out of St. Cloud and hopping freights, and I fell in love with it right away. I mean, I like hitchhiking because you get to meet a lot of different people, but the freight-train riding was like the freedom, you know? —Ricardo

I first left home when I was 16, just to see the country and get out on my own for a while to see if I could do it. And I did. —Minnesota Jim

My father was a hobo, born in 1898 in Frog Level, North Carolina. Ran away from home when he was 12 or 13, rode freights for about 17 years. He’s a wonderful storyteller, musician, singer. He was always the one to tuck me in bed at night. He would say, “Two songs, one story. You get to choose one song, and I’ll choose one.” I always chose “Cocaine Jubilee,” because he learned it out in the opium dens and it was a funny song. Then he would sing one, and he’d tell me one of his adventure stories.

I remember when he’d leave every night, I’d think, “I can’t wait until I’m old enough to do that.” I started hitchhiking right out of high school and eventually was a student at Indiana University. I had the honor of doing a directed writing course which I could choose the professor. He said, “You need to choose a good topic.” And I chose hobos, and I said, “Because I grew up with it.” —Gypsy Moon

When I was a really young kid, I lived in a neighborhood in Houston close to a big train yard. It’s had a hobo jungle there for a long, long time. I had a buddy named Dusty, and me and Dusty used to sneak out there in the field and watch the hobos. We used to watch guys get on and off the trains all the time, so we kind of knew how it all worked.

Dusty and I did catch a train, to Galveston. We just got on the train in the dark. We got down there, and we’re like, “We’re 60 miles from home, how are we going to get back?”

Maybe half an hour later, there was a train going the other way, rolling real slow. We saw empties. We caught a train going the other way, and by sheer luck, it went right back to the same place we were at. We were just really lucky. —K-Bar

* * *

Britt is a small town in north-central Iowa. Maybe 2,000 souls. Tidy lawns and houses. A handful of shops and restaurants. A few vacant storefronts. Nice library and municipal building, and the police station used to be the dentist’s office. Dan Cummings, the chief at the time, just brought in a new popcorn maker he’s pretty happy with for the jail.

Twenty-five minutes east is Clear Lake, where Buddy Holly’s plane went down; 25 minutes west is Algona, where the motels are—and the McDonald’s and the Hormel pepperoni plant and the factory where they make Snap-on tool boxes; 10 minutes north is the Crystal Lake Wind Farm and its long horizon of bright white turbines, and 15 minutes past that is the Winnebago factory over in Forest City. Everything else this time of year is corn; corn to the distant edges of the world, corn and more corn, and the kind of immaculate farms for which Iowa is known.

The train tracks run east-west through Britt. There’s been a railroad in and out of here since about 1870. First hobo probably rode through not long after. Used to be a Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul line; then the Iowa, Chicago and Eastern. Now it’s the Dakota, Minnesota and Eastern Railroad. Mainly freight lines, carrying mostly grain.

(Alyssa Schukar)

We’re all here for the 118th National Hobo Convention.

Along with the County Fair and the Draft Horse Show, the Hobo Convention is the biggest thing on the Britt calendar.

From what I have gathered over the years growing up in Britt, it started in 1900, where two businessmen had heard about this convention happening in Chicago, and they thought, “Why don’t we go out there and see what it’s about, and maybe that’s something we could bring to Britt, bring people into Britt, and business.” —Amy Boekelman, president, Britt Hobo Days Association

My favorite part is starting the week before, there’s a lot of hobos in town, and I try and go down to the jungle almost every night up until like Wednesday and Thursday when we get really busy on the festival. But it’s those nights in the jungle just talking that are some of the best. You hear the old stories, everyone’s reminiscing. A lot of them will share stories of riding with some of those steam-era hobos who used to come to Britt and aren’t here anymore, so it’s finding that common connection and they’re so welcoming to people from the community and they love sharing their stories. To me, that’s what it’s all about, and I’ve formed some great relationships with several of them now. —Ryan Arndorfer, mayor, Britt, Iowa

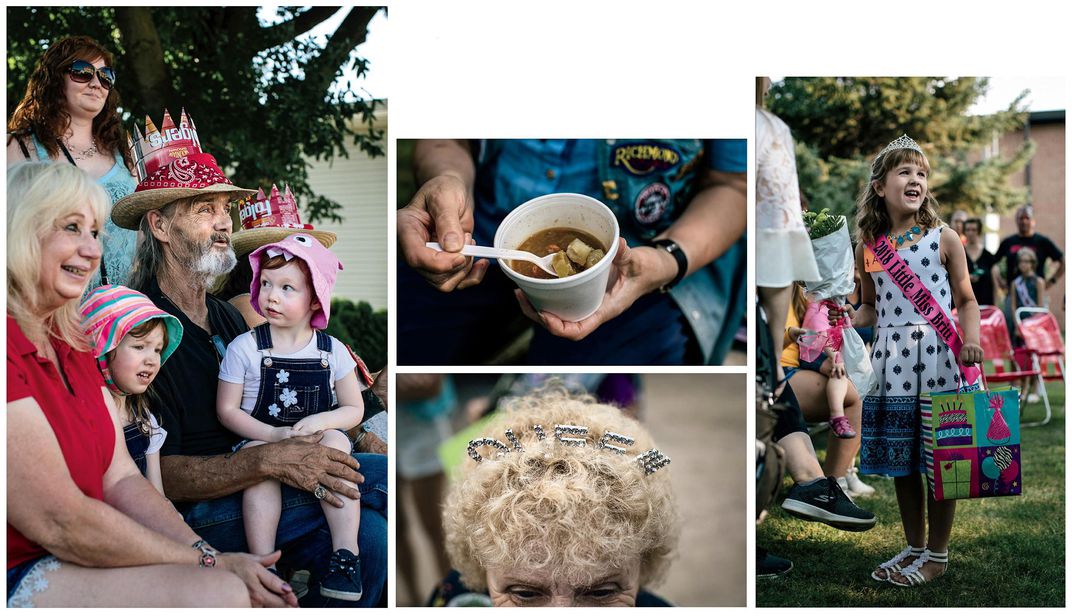

There’s a carnival midway on Main, and concerts and dancing on the bandstand, and the selection of the new Hobo King and Queen, and their coronation and the big mulligan stew feed in the park, and the car show and the Hobo Museum is open and the Hobo Art Gallery too, and there’s Mary Jo’s Hobo House café, and the Hobo Omelet Breakfast Fund-Raiser and the Vagabond Craft Show, and the Four Winds Ceremony and the Toilet Bowl Races and the ice cream social. But the greatest of these, by far, is the parade.

Everyone in town is either in the parade or watching the parade, or in it then watching it, or watching it then running around to get back in it. Entire high school classes come home to sit on a bale and ride a flatbed pulled by a tractor. Turns out the hobo convention is a reunion for the whole town. The Iowa State Fair starts the day before, so everyone comes home.

The hobos have come here every year since 1900.

* * *

The history of the hobo is the history of modern America. Starts right after the Civil War and the building of America’s great railroads. There had always been a small floating population of agrarian workers, but they were limited by geography and technology. They were regional. Local. Language historians and etymologists aren’t sure, but the word “hobo” may come from this original population of farmworkers: “hoe boys.”

The railroads change all that. After the war there’s an expanding displaced population available to ride—and help build—a transportation network running from coast to coast. As this is happening, America is industrializing too, and the need for a mobile work force, willing, adaptable and relatively inexpensive to transport, becomes evident. The hobo.

(Alyssa Schukar)

By the late 19th century, the heart of Hobohemia was the main drag in Chicago, where train lines radiated out into every corner of America. It was easy to find work there in the slaughterhouses to make a buck before you caught out again; easy to go west and build a dam or go east and take a job in a new steel mill. So for decades it was America’s hobo home. The Hobo Code was written there in 1894, an outline of ethical hobo practice and communal etiquette. Based in mutualism and self-respect, it remains every hobo’s founding document, a simple and forthright set of instructions to live by. The same year, Coxey’s Army of the unemployed makes its protest march on Washington.

The country is growing in booms and busts, and transient work like lumbering and mining and seasonal fruit picking are moving west into parts of the country without much population, so the hobo follows. And in the same way coffeehouses were indispensable to the American Revolution, railroads and hobos become an integral part of the modern U.S. labor movement, especially in the Pacific Northwest.

The Industrial Workers of the World, its members known as the Wobblies, is founded in Chicago in 1905. Its radical labor politics and spirit are then widely and passionately distributed by rail, by hobos coming and going around the country, like an injection into the national bloodstream. One of the founders of the American Civil Liberties Union, Roger Baldwin, was an IWW hobo. But the greatest of these, and most famous, was Joe Hill. A martyr to corporate violence and the solidarity of labor, he remains America’s best-known hobo.

Hobos came and went on the huge historic construction and infrastructure projects of the American West, and ridership rose and fell with the national economy. A surge of young men after World War I, another in the Great Depression. For decades fruit tramps are hauled west by rail, picking the produce that would soon ship east by boxcar at a premium price. That symbiosis held until trucks took over so much of the nation’s shipping.

When the veterans came home from World War II, they bought cars or motorcycles and rubber-tramped. Fewer and fewer depended on the railroad. Populations of employable Americans filled in almost every corner of the map. Eventually that mobile surplus labor force became less necessary to the national economy. Even the old art forms, like the hobo nickel and the wooden cigar box carving, were slowly being lost.

The transition from steam to diesel marks the beginning of the end for the Great Age of the Hobo, and the numbers have been declining ever since. After 9/11 it becomes so hard to hop a freight that only a few hardcore hobos remain.

There’s a team of archaeologists exploring a hobo jungle at a dig in rural Pennsylvania. It’s easy to feel like the hobo has already passed into history. From the Hobo Code to the “Hobo Code” episode of “Mad Men” in about 113 years.

(Alyssa Schukar)

To have been a hobo—or a tramp or a bum—is a pretty loosely held title, hard to pin down biographically. You’ll see lists in books and online of famous hobos. I suspect plenty of the names reflect a long summer’s walk rather than a life on the rails, or a sentence fragment in a press release to help sell an album. They were scenery bums. Still, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas is thought to have hoboed his way across country to attend law school. Writers James Michener and Louis L’Amour and Jack London, and billionaire oilman H.L. Hunt, all went on the bum. The best description of Jack Dempsey, hobo and heavyweight champion of the world, was written by Jim Murray, one of the greatest sportswriters who ever lived:

“Whenever I hear the name Jack Dempsey, I think of an America that is one big roaring camp of miners, drifters, bunkhouse hands, con men, hard cases, men who lived by their fists and their shooting irons and by the cards they drew.”

* * *

By the end of the 19th century, all that steam-engine tramping and rail riding and the romance of what lies past the horizon begins to appear as a subgenre of our national literature. Bret Harte’s “My Friend the Tramp,” a short story from 1877, is an early exploration of the interpersonal politics and impossibly high price of radical individualism. Jack London gathers his own hobo stories first as a series of magazine pieces, then as a mashup of fiction and nonfiction in 1907’s The Road. Vachel Lindsay and Robert Frost are early poets of the form, and Frost’s “The Death of the Hired Man” may be our most wrenching depiction of leaving home and returning home, of itinerant work and our obligations to one another:

Home is the place where, when you have to go there,

They have to take you in.

By 1930, when John Dos Passos writes The 42nd Parallel, the first novel of his towering U.S.A. Trilogy, the hobo is no longer just a foil or a cautionary tale, but the protagonist, often driven away from home and into the world by injustice. As we see again in John Steinbeck, and The Grapes of Wrath, the hobo, the landless, the migrant, becomes a Christ. That impulse travels all the way up the line to Jack Kerouac and the Beats.

By then there was plenty of social science writing about hobos too, the most famous being The Hobo: The Sociology of the Homeless Man by Nels Anderson, 1923. In the years since, hundreds of other books and studies and dissertations have drawn on its initial research. And once every ten years or so, another writer hops a freight and writes a book about it.

Hobos have been stock characters in the movies since the days of the hand-cranked nickelodeon. Charlie Chaplin took the American hobo global. His Little Tramp is the bittersweet flip side of radical labor politics and industrial/agrarian alienation. Always broke but never broken, his struggles were everyone’s. By camouflaging it as comedy, he presented us then—and presents us still—the tragedy of modernity. Every hobo is a commentary on capitalism.

There’s the hobo played for laughs again in director Preston Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels, and Gary Cooper in Frank Capra’s Meet John Doe, but the summit of the early Hollywood hobo form might be William Wellman’s Wild Boys of the Road from 1933. Meant to discourage Depression-era runaways and warn young Americans about the risks of vagrancy and the hobo jungle, it had the opposite effect, and was so thrilling it became a kind of recruiting instrument. The postwar American hobo, the TV hobo—Red Skelton as Freddie the Freeloader, or Emmett Kelly as Ringling Brothers’ sad circus clown—had the unintended effect of reducing the hobo to a punch line. (You see this in how those well-meaning SDSU students costume themselves. It’s a baggy-pants vaudeville with a five o’clock greasepaint shadow.) The 1970s delivered Emperor of the North Pole and Bound for Glory, two of the best, and last, movies of the genre.

Bound for Glory is the story of singer-songwriter Woody Guthrie, and that’s where the mythology of the American hobo will likely live forever, in music.

Go back to the American folk songs of the 1880s and ’90s and you’ll hear the beginnings of what became the IWW’s Little Red Songbook. In it, you’ll find the roots of everything and everyone from Woody Guthrie to Pete Seeger to Bob Dylan, Phil Ochs and Arlo Guthrie and John Prine, Steve Earle and Bruce Springsteen. One of this country’s 20th-century greats, modernist composer Harry Partch, was a hobo.

* * *

There are events in Britt all week, beginning, ceremonially anyway, with the lighting of the jungle campfire, in which the hobos call down the blessings and benedictions of the Four Winds. This they do in the breezeless summer heat, and the next few days will be spent walking back and forth from the jungle to the midway and the park and the museum. Most of the ’bos come back here to eat at mealtime, and Hawk, the Crumb Boss, sees to it that everyone gets three squares a day. There’s always coffee, too, and he makes sure everyone drinks a lot of water, “Gotta hydrate, man.” Everyone drops what they can in the kitty to pay for it all.

Over at the Hobo Art Gallery, they’ve unveiled the portrait of Tuck and Minnesota Jewel, last year’s king and queen. The walls are lined with these paintings of past royalty, including legends like Iowa Blackie and Bo Grump. The portraits are all painted by Leanne Marlow Castillo, a local artist of skill and renown. She is 85. “I did it all on my own. I was asked to restart an art show. I started painting them, and I painted six the first year, eight the second year.

I’m still around.”

(Alyssa Schukar)

Across the street at the Hobo Museum—the old Chief movie theater—they’ve got case after case of memorabilia donated by the hobos themselves going back generations. There’s a good PBS documentary running on a loop down in the little screening area. During Hobo Days, the mayor himself works at the counter.

Start Saturday in the little park by the gazebo, but start early—the big pots of mulligan stew went on the boil long before sunrise. This year’s crew is made up of a dozen local home-school athletes, sleepy-eyed and still yawning, every one of them stirring half a dozen giant, steaming cauldrons with what look like canoe paddles. The recipe is simple, which is roughly true to the origin of the dish: Whatever the hobos had went into the pot. This morning it’s a ground pork stew with plenty of potatoes and carrots and cabbage, rice and barley, onions and chili powder in a tomato-paste base. By 11 in the morning there’s a line to get it by the cup.

Up in the gazebo, there’s a radio broadcast of the parade, and it goes out over the PA and everybody within a few blocks can hear it. That’s pretty much everyone in Britt. The old-timers set up their lawn chairs on the sidewalk, and lots of folks from out of town stand lining the streets and spooning up free stew.

The parade snakes a long S-shape through town, doubling back on itself. It’ll take more than an hour for every car and float and motorcycle to pass wherever it is you’re sitting or standing. Which is OK, because they’re all throwing candy at you. It’s a pre-Halloween chance for the kids—and some of the quicker adults—to load up on sweets. I was out front of the fire station for most of it, and caught licorice whips and bits and pieces of conversations as they went past.

“I remember when this was bigger…”

“…when these men were heroes…”

“…real hobos like Steam Train Maury…”

“Did you see that old Plymouth?” which is a question asked by a guy driving an old Pontiac. There are scores of old cars and trucks, vintage and not, some of them carrying politicians, like the mayor, others carrying signs for politicians, “Vote for Schleusner for Supervisor,” and one carrying a cardboard cutout of the pope. Those SDSU students, here doing research for their own homecoming Hobo Day, are out in their tin lizzie, waving and honking and having fun. There’s a 1946 Farmall tractor pulling the class of 1998, and there’s the class of 1978, and the class of ’93; there are floats from the churches (“Here come the Methodists,” says the man to my right, to no one in particular) and from the seed companies, “the Future of Farming at Work” reads the sign; and the golf cart advertising the local lunch counter, and then the class of ’88 and the class of ’68 and an old man in a tall straw hat astride a horse, then the Knights of Columbus and the polka band on the flatbed sponsored by the veterinarian. The local co-op, the local college and the local veterans group go by, as Lee Greenwood’s “Proud to Be an American” shakes the trees, and the hobos pass by on their trailer, holding signs like “The Dutchman for King,” and IoWeGian walking next to the giant chicken from the local bank alongside a nice 1968 Camaro.

(Alyssa Schukar)

Then it’s time to elect a new king and queen. The little park is packed shoulder to shoulder.

To get things started, hobo Luther the Jet sings what sounds like the second verse of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” Luther is rumored to have a PhD in French literature and a faculty chair somewhere, but is notorious for slipping away at these gatherings and does so before I can get to him. In any case, it’s time for the speeches. Every candidate for king and for queen has a minute or two to state their case. At the end of the speeches, the audience votes by applause and the judges crown the victors.

The odds-on favorite for king this year is Slim Tim.

“Hi. I’m Slim Tim. My dad Connecticut Slim was crown prince of the Hobos for life. My two sisters Connecticut Shorty and New York Maggie were queens of the Hobo. If you elect me, I will promote Britt Hobo history. I also will help to make the old State Bank into a hotel, which Britt really needs. So more people can stay in Britt and know what a great stay it is. No matter who you vote for, I hope it’s me, but I will always be a promoter of Britt and the Hobos because I love them both, so be happy and have fun. Thank you.”

There is a round of polite applause.

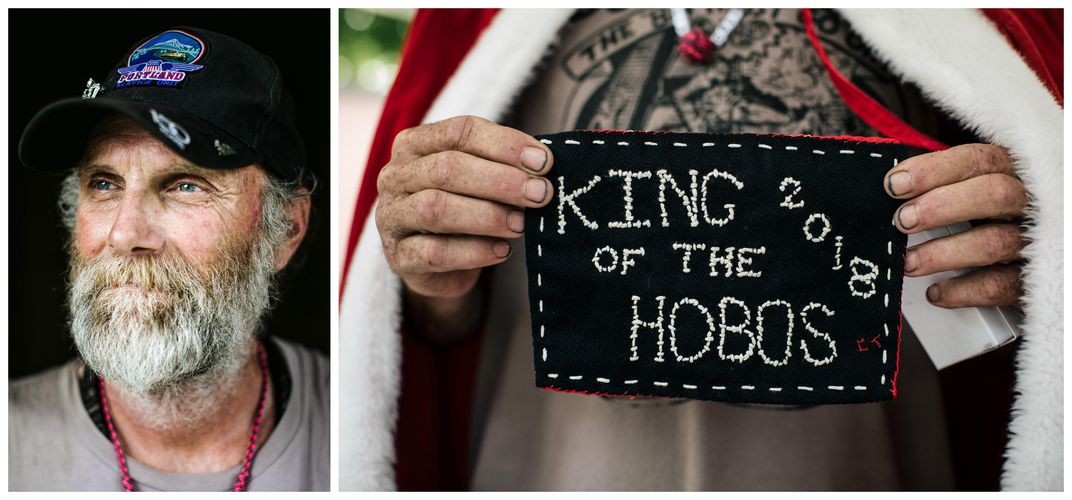

Then the dark horse, the Dutchman, who no one gives much of a chance.

“First, I’d like to say to the good people of Britt I surely appreciate your hospitality, and the real fine sit-down you’ve put on. This is very special. I’m touched. Really. Second, I’d like to say that I’ve been on the road since 1968. That’s 50 years of riding trains and wandering places, chasing disasters.

“Everything I’ve owned, and everything I want in life, fits in this house [points to his knapsack], right in my pack. Anything that doesn’t fit in my pack, I can’t carry with me. I don’t want it. I can’t have it. It all gets left behind. It makes me a different kind of person. It’s given me something special in life. I’m not attached to anything. I wander with the winds. I know that a lot of people wish they could do the same.

“It’s a hard life in a lot of ways. It probably shouldn’t be romanticized the way that it is. You get yourselves out there, and it’s cold, wet, and the steel is hard. It’s very dangerous. There are people out there that aren’t very nice. But I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It takes a lot. I’m a man of few words.

“So, I think that’s about all I need to say. Only that…one last thing, I got 15 states of dirt on me, and these pants are brand new.”

The crowd goes pretty crazy.

Half Track’s daughter Crash is running for queen.

“When I decided to run for queen, I had no idea what my speech was going to be, so I decided to speak from the heart. Now, I grew up with the hobos, they came to my house. They even took me on my first ride, all the way to Long Island, New York. That was very exciting, but they’ve been a family to me, and so has Britt. Britt has been an escape since I was a child. I know I missed a few years, but I’m back, I’ve got my kid this year. And I would love, really love to show the people out there, the world, what the wealth that the hobo family and that the town of Britt shows, because this is one of the best places. I’ve never felt more welcomed or accepted than anywhere I’ve ever been. Thank you.”

(Alyssa Schukar)

The final question music from “Jeopardy!” plays while a selection committee officially confirms the audience choice.

Dutch and Crash both look surprised and sheepish, but happy, in their robes and crowns. Ecce Hobo.

It is a fair accounting of the day to say there were 2,500 attendees—and 2,500 participants. The crowd disperses up and down Main Avenue after the coronation, and you see Queen Lump, a former winner, walking slow, and Minnesota Jim, and the sun’s hot in the street and the smell of fried dough and midway grease is thick in the heat, and the music and the clatter from the rides are loud and by the end of the day that Hobo Omelet breakfast might raise $2,500 or more, they tell me.

The carnies are all parked in their campers over on East Center Street, just up the block from the Toilet Bowl Races—a timed, point-to-point-to-point event involving teams of three pushing toilet bowls on wheels, the rapid consumption of popular snacks, a great deal of toilet paper and many teeny-weeny toilet trophies. Whatever it is you’re imagining it to be is no worse than whatever I might write about it actually being.

Our kids grew up here and they’ve been in the hobo jungles all the years. My daughter has one of the Steam Train Maury walking sticks from way back when. So our kids are now grown and they come back to Britt with their kids. And now we babysit the kids while they do a little bit more of the activities. I’ve lived here 43 years. It’s a tradition that I hope will always stay alive. —Sally Birdman

Best scene of the week was certainly this: Tuck and Jewel, as the outgoing King and Queen of Hobos, have a “photo op” up by the library. Which means they’re sitting on a park bench across from the museum, and you can walk up to them and ask to sit for a picture. This they do, graciously, and every couple of minutes a citizen snaps a selfie, or gets a portrait made with royalty. There’s small talk and handshakes and thank-yous and the whole thing is as unremarkable as it sounds.

Folks come and go, but one man hovers a few feet away for a while and watches it all with interest. He looks a little like Tuck, especially around the eyes, about the same age, but rounder, without the hollows in his cheeks. Cautiously, he steps forward.

“Do you remember me?” he asks. “I’m your brother.”

They haven’t seen each other for 30 years.

Tuck stands and says nothing and takes the man in his arms and everyone around the bench dissolves into tears. They hold each other a long time.

The lights on the rides are coming on, and the last thing I see on the midway is a happy kid, maybe 9 years old, running past us with a souvenir dreamcatcher as big as a manhole cover.

* * *

The Dutchman’s blue eyes are bright even in the half dark of the boxcar. He is lean and windburned, red-cheeked and gray-bearded. Sixty now, he’s been on the road 50 years. His father chased him out of the house. He was always in dutch back then, and the name stuck. He’s smart and forthright and there is no menace to him, but the clarity of his purpose and the rigor of his personal philosophy can be unnerving to the citizens and the straights. When he’s not catching out, he’s catching work as an electrician. As you read this, he’s as likely to be in California as he is in Indiana. Or riding the porch of a grainer anywhere in between.

In passing you’ll hear that “Dutch owns the boxcar,” and it won’t matter if they mean this literally or figuratively. The boxcar is a fixture in the Britt jungle, permanent. Long off the main line and set here years ago, it is a meeting place and a memorial, an antique keepsake and a hideout. Dutch sits with his gear at the north end of the car. Everything he owns fits in a knapsack. Heaviest thing he carries are his memories. Folks come and go, talking. The Dutchman is a focused listener. Intense, even at rest. As often as not, he’s up there with the younger ’bos, the newer riders, answering questions and giving tips. (For insight into this next generation of gutter punks and crusties and dirty kids, the postmodern hobos, search out the stunning photography of Mike Brodie.)

Dutch is one of the motive forces of the Bo-lympics, an 80-proof skills and athletic competition among newly minted hobos. And now he’s the king. He even did a TV interview up in the boxcar this year.

“You ain’t free until your backpack’s full and your pockets are empty,” he says.

(Alyssa Schukar)

Every culture has its seekers and its pilgrims, its mystic beggars and holy wanderers, its ascetic prophets and barefoot madmen, its itinerant poets and singers. Buddha and Moses and Jesus all went on the bum for a while too, don’t forget. And some of this metaphysical shine rubs off on the hobo, who may or may not be looking for enlightenment. Those holy men want you to get rid of things to free yourself from wanting. To give away everything is to pass out of this world, or into heaven, untroubled. A point made one way or another at hobo church on Sunday morning by the fire. But then why is every hobo song so sad?

Tuck and his brother are huddled up on a couple of patio chairs near the pavilion. “We never thought you were dead,” his brother tells him, “but we always wondered where you were.”

* * *

The Evergreen Cemetery in Britt is bigger than you expect and this morning it’s all sunshine and fine blue sky. There’s Tuck and Jewel with their walking sticks and there’s Redbird and Skinny and Slim, and George and Indiana Hobo and Connecticut Tootsie. We’re all here to say a ceremonial goodbye.

There’s something profound in all this, in the week, something ancient and right and good, of townspeople taking in the stranger, the poor and the lost and the hurt, of the Samaritan, of Moses and Buddha and Abraham. Five thousand years of wandering and it turns out the real wilderness is inside us. Hats off and heads bent, the Square Johns and the tramps and the hobos, the citizens and the bulls take each other’s hands, and all at once you see it, the community and the humanity and the love.

(Alyssa Schukar)

But the Dutchman’s right, too. Don’t romanticize it. Empty your pockets. Empty your heart. There’s only what you carry on your back. There’s whatever you’re chasing and whatever’s chasing you. Maybe there’s some grace to be won in the burdens you bear, or in your swiftness, but at moments like this it feels like the price of your freedom is an unimaginable loneliness.

They call the roll, and Half Track reads the names, of those who caught the westbound, those gone before us, friends, strangers, the loved and unloved, the not yet forgiven and the not yet forgotten, not yet, and everyone closes their eyes to pray and the cicadas lathe the trees and the heat rises and the honor guard steps forward in a stiff-legged line of flags and rifles, older men mostly, from the VFW and the Legion hall, all American belly and grim solemnity, jackets too tight and ramrod straight with duty and country and for a moment the whole thing rides a thin line between comedy and tragedy and then they play taps and you realize you’ve been crying for a long time. Because here we are.

Home at last.

[ad_2]

Source link