ART NEWS

State of the Union: Faith Ringgold at Glenstone

For decades, Faith Ringgold has invited the dark shadows of American life onto the nation’s bright face, chronicling its grim histories, untold betrayals, and unsung heroes. The sound-bite description of the artist—Black Power activist, feminist, maker of story quilts—subsumes the complexities of her fulsome vision and personal voice. Her politics, while prophetic, earned her little respect within the mainstream art world or among her peers in the 1960s and ’70s. With more than seventy artworks hung mostly chronologically, the Glenstone Museum’s survey, organized by the Serpentine Gallery in London, elaborates on the context and development of Ringgold’s work across genres (early figuration, political posters, soft sculpture, quilts) and historically bound series, including “American People” (1963–67), “Black Light” (1967–69), and “Feminist Series” (1972). It is the most expansive exhibition of Ringgold’s work to date.

Related Articles

The first galleries introduce “Super Realism,” Ringgold’s signature style of abstracted figuration and sharp graphic and conceptual contrasts, which she developed to address the halting progress of the pursuit of social and political equality in the United States. Flat planes of color edged in black delineate the figures of her early work from the 1960s, where compositions often illustrate tense interracial relations—people torn between peace and violence, ambivalence and anger. In American People #4: The Civil Rights Triangle (1963), a white man stands above, yet behind, a phalanx of four darker-skinned men; his symbolic participation is removed from the corporeal vulnerability so central to the social justice movement.

The ideals represented by “America”—equality, liberty, and justice—are more literally overwritten (by images of bloodshed and the phrase “white power”) in later works reflecting the violence following Malcolm X’s assassination in 1965. Ringgold famously contorted the American flag into a structure of confinement in American People #18: The Flag Is Bleeding (1967). Red stripes enclose a white woman and the two men, one white and one Black, with whom she links arms; white stars obscure the face of the Black man, who holds a knife in one hand and covers a seemingly self-inflicted wound with the other, his blood the same vermilion as the flag’s.

Faith Ringgold, American People #4: The Civil Rights Triangle, 1963, oil on canvas, 36 1/8 by 42 1/8 inches. Photo Ron Amstutz. Courtesy Glenstone and ACA Galleries. © 2021 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Ron Amstutz

Ringgold works the imagery and formal elements of the flag into stretched canvases, hanging textiles, and quilts, compositionally loosening its bounded stripes into pieced squares and linear borders—transfigurations that suggest Old Glory can withstand critique while retaining its symbolic potency. She was punished for this: along with the two other members of the “Judson 3,” the co-organizers of “The People’s Flag Show” at the Judson Church in 1970, she was accused of flag desecration, and arrested. That history emerges here through a handful of Ringgold’s political posters, but unfortunately her other art “work”—picketing with her daughters in front of the Whitney Museum in 1971, co-founding Where We At to support Black women artists—is relegated to wall text.

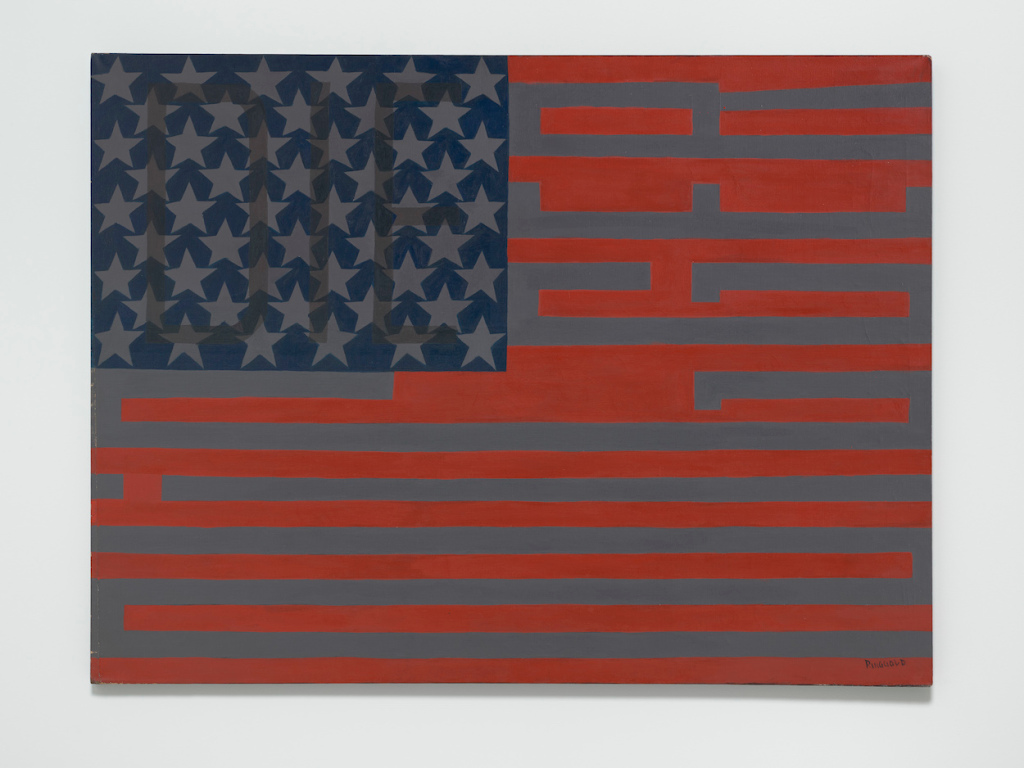

In mining American iconography, Pop art, and minimal painting for visual strategies to be used politically, Ringgold built on the socially motivated abstraction of her teacher Robert Gwathmey, as well as the tactics of Picasso, whose 1937 painting Guernica inspired Ringgold’s tour de force American People Series #20: Die (1967), sadly absent here. In the “Black Light” series (1967–69), Ringgold omitted white pigment, yielding inky compositions that signify the dark afflictions of American life. Geometric arrangements of figurative elements allude to inter- and intra-racial tensions and to the kaleidoscopic vision of Black Power ideology, which offered solidarity, community, and ancestral pride even as it plainly confronted an anti-Black reality. Black Light #10: Flag for the Moon: Die Nigger (1969) is the most harrowing: the letters in “Die Nigger” are disguised within the stars and stripes of a sullen flag.

Faith Ringgold, Black Light #12: Party Time, 1969, oil on canvas, 59 3/4 by 85 1/2 inches. Photo Ron Amstutz. Courtesy Glenstone Museum and ACA Galleries, New York. © 2021 Faith Ringgold / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Ron Amstutz

Ringgold’s work decenters the white nationalism of American narratives while reminding us that the killing of innocents is part of the nation’s life cycle, recorded in an intergenerational wound. The “Slave Rape” series (1972–73) imagines the female victims of the transatlantic slave trade, represented by a pregnant Ringgold and her two daughters. In each of the three pieces on view, a bare-breasted woman peers out from the insufficient cover of red, orange, and green leaves. One is seemingly paralyzed with fear, another turns to run away, and the third stands ready to fight, axe in hand.

These works are among Ringgold’s “tankas,” inspired by an encounter in Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum with Tibetan thangka, textiles whose portability, combination of inscriptions and images, and contrasting borders made them everything that American painting was not at the time. Clear precursors to Ringgold’s story quilts, these textile works also offer intercultural and intergenerational messages of hope and healing; they clearly anticipate and sanction the work of later Black women artists—from Emma Amos and Howardena Pindell to Tschabalala Self and Sonya Clark—who have interwoven painting and craft in vibrant celebrations of the Black female spirit. Glenstone’s policy of not admitting children under twelve is a missed opportunity to further this influence.

Rounding out the exhibition, the quilts that include text, some honoring great African American figures such as Sojourner Truth and Martin Luther King, Jr., tell stories that images alone cannot—most important, those about individual and political change. Throughout the show, QR code labels offer transcriptions of often inscrutable painted inscriptions, aiding viewer engagement and revealing additional dimensions of Ringgold’s ideas. One quilt, The French Collection Part 2: #11, Le Café des Artistes (1994), represents a multiracial group of artists and intellectuals—among them Romare Bearden and Lois Mailou Jones—at a Parisian café. This imagined gathering is narrated via a letter, supposedly written by the abandoned wife of the café’s former owner, which literally shapes a discourse around the painting and conveys the protagonist’s thoughts on primitivism, sexism, tokenism, identity politics, and Africanity. The real author is, of course, Ringgold, orchestrator of conflicts and reunions that expose the interconnectedness of the individual and the social, the personal and the political. Ringgold shows that all those hard edges and soft forms, joyful colors and painful structures, and possibilities of struggle and sanctuary are part of the same story.