ART NEWS

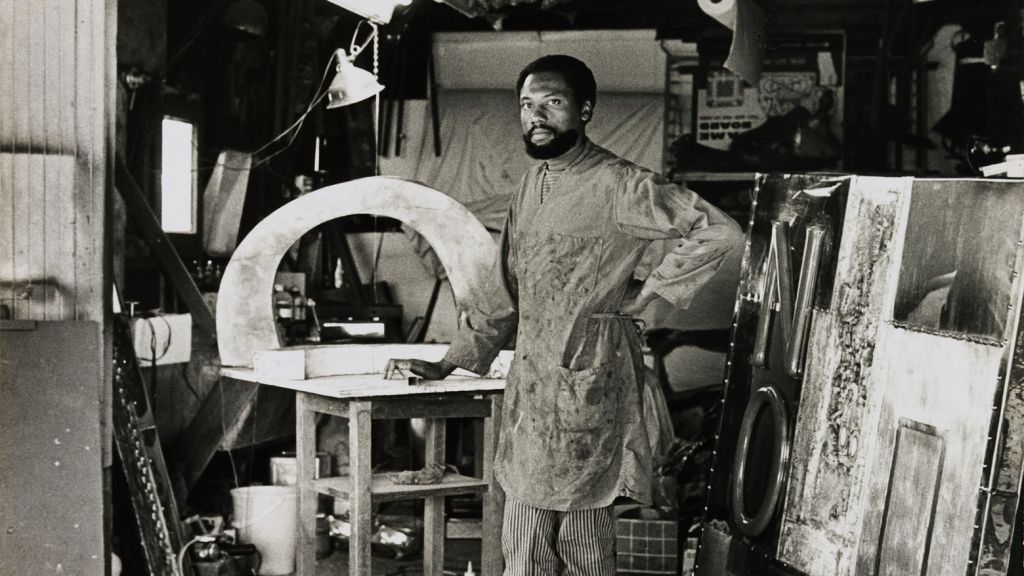

John Outterbridge, Sculptor Who Broke Down Barriers Between Life and Art, Has Died at 87

John Outterbridge, a sculptor who made the stuff of everyday life his medium, crafting found objects into assemblages imbued with history, has died at 87, according to New York’s Tilton Gallery, which represents him. No cause of death was given.

Outterbridge’s sculptures often feature objects scavenged from the streets of Los Angeles’s South Central region, where he was long based—worn-down rags, dirtied pieces of wood, and other scrapped objects. In bringing the everyday world into institutional and gallery settings, Outterbridge effectively suggested that life and art could not be divorced.

In interviews, Outterbridge often said that he began making assemblages during the 1960s after simply being inspired by what he saw around him. In a 2013 conversation with Art in America, he described his father as a “man who found esthetics in his backyard” and his mother as someone who clipped away pieces of her reading materials. “Many of the esthetics existed all around me, done by people who didn’t find it important to put a signature on anything,” he said. “They just made it. And that’s what I had in my system.”

Related Articles

Outterbridge’s constructions of everyday materials were political in nature. His series “Containment,” from the late ’60s, focused on the constriction of bodies throughout history. When these works debuted at L.A.’s Brockman Gallery—a Black-owned space that also mounted key early shows by David Hammons and Noah Purifoy—in 1971, Outterbridge wrote, “To contain is to hamper investigation and growth, resulting in the creation of strange ideas fragmenting even stranger concepts, cold and distant.”

Among the works in that series is Strange Fruit (Containment Series), 1969, in which rectangular segments of metal are welded together, forming a frame around a recessed element filled with what appear to be tiny skulls. Its title alludes to a song by Billie Holiday focused on the lynching of Black Americans in the South.

And in a 1970s body of work called “Ethnic Heritage Series,” Outterbridge crafted various materials into dolls. Some objects in the series look like African artifacts, others resemble something more surreal. In Broken Dance, Ethnic Heritage Series (ca. 1978–82), steel, fabric, and wood are sculpted into an armless, headless figure with splayed legs, one of which rests atop an ammunition box with an antenna attached, hinting at a kind of unseen violence.

John Outterbridge, Broken Dance, Ethnic Heritage Series, ca. 1978–82.

©John Outterbridge/Courtesy the artist

Outterbridge began making these works against the backdrop of a radically changed Los Angeles. In 1965, many Black residents protested excessive use of force by the police in what has been termed the Watts Rebellion. Following that series of protests, Black artists began reevaluating the relationship between themselves and the city surrounding them, with creators such as Purifoy, Judson Powell, Melvin Edwards, and others relying on urban detritus in their work. Outterbridge once said of his own art, “The work engaged part of the experience of the reinvention of things.”

Around this time, too, Outterbridge became acutely familiar with the systemic racism that exists within museum walls. He took a part-time job at the Pasadena Art Museum in 1967. At the time, the institution had become a nexus of avant-garde activity, and in his time there, Outterbridge met Andy Warhol, Richard Serra, Robert Rauschenberg, Mark di Suvero, and other artists of note. But his experience was not always a positive one. He recalled how, in a 1968 survey focused on East Coast art in the postwar era, there were no Black artists, even though ones such as Romare Bearden ought to have figured. “I found out that museums are strange places,” Outterbridge said in a 1973 oral history with the Smithsonian Archives of American Art. “I started to feel that museums were kind of tombs.”

Instead, Outterbridge struck out on a route that mostly saw him working outside mainstream institutions, in an attempt to engage with his own community. In 1970, Powell invited him to begin teaching at the Compton Communicative Arts Academy, which was situated in a majority Black neighborhood. “The concept we’re trying to develop is that there’s a place for everyone, that everyone is creative, that groups of artists can come into a community and use that creative energy to get a lot of things done,” he said in the SAAA oral history. Later, in 1975, he became director of the Watts Towers Art Center, which is home to an art space and helps facilitate community-oriented educational initiatives. He remained the center’s leader until 1992.

“I don’t know if I could ever leave this, and go back to the loneliness of producing my own work,” he said. Then he went on to do just that.

John Outterbridge was born in 1933 in Greenville, North Carolina. He attended A & T College in Greensboro, and then went on to serve in the U.S. Army, where he was stationed in Germany. (He had attempted to join the Air Force, but was unable to because, at the time, quotas were being imposed on how many Black members there could be.) While in Germany, he began experimenting with painting, all the while focusing on his work as an ammunitions specialist. After his stint in the Army, he lived in Chicago, where he attended art school, and then moved with his wife to Los Angeles in 1963.

John Outterbridge’s 2011 show at LAXART.

Courtesy LAXART

After two decades working primarily as an educator, Outterbridge left his post at the Watts Tower in 1992. He returned to art-making once again, representing the U.S. at the Bienal de São Paulo in 1994 alongside Betye Saar. Still, even as he worked in his studio, he focused on the value of arts education. In 1994, amid the possibility that L.A. would cut back on the budgets for art educators to children, he told the Los Angeles Times, “The arts sometimes give language to young people who simply would not have language that speaks to life, that speaks to life potentials. Should we subtract the arts from our culture, we wouldn’t have very much left at all.”

Although Outterbridge was a crucial figure within L.A., having gotten a retrospective at the California African American Museum in 1993, it was not until the past decade that his work began getting major surveys at the world’s top institutions. Over the past few years, his art has been featured in several major surveys, among them “Soul of a Nation,” a traveling show focused on the Black Power movement and art-making that opened first at Tate Modern in London in 2017; “Outliers and American Vanguard Art,” a show about self-taught art that opened at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. in 2018; “Like Life,” a 2018 exhibition about the human body and sculpture over the years at the Met Breuer; and the recent permanent collection rehang of the Museum of Modern Art in New York. He also was included in the 2013 Venice Biennale in Italy and had a solo show organized by the Hammer Museum in L.A. that took place at Art + Practice in 2015.

In recent years, Outterbridge began relying more heavily on rags, which he turned into sculptures evocative of flags. “You just can’t get away from rag; even when you throw it away it comes back to you,” he told Artforum in 2011 on the occasion of a LAXART show. “It’s like water, nourishing to your character, to the character of the cast-off, and to the way we practice living.”