ART NEWS

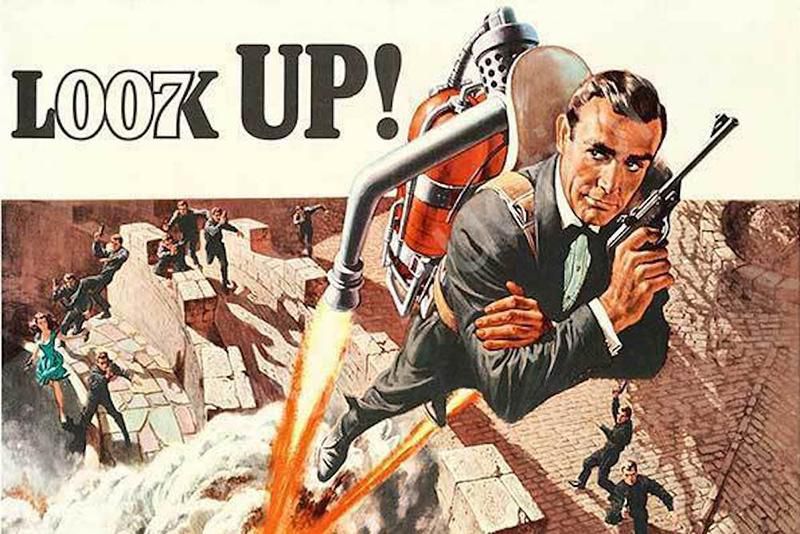

In Battles of Man Versus Machine, James Bond Always Wins | Innovation

[ad_1]

Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels have been enjoyed by a global audience since the 1950s, and the films constitute the longest running and most profitable franchise in the history of the movies. This fictional character is a global icon admired by millions.

What explains 007’s enduring appeal?

Adventure, guns, and girls, surely. But Bond’s long-standing popularity can’t be separated from our relationship with technology. The Bond character consistently embodies our ever-changing fears about the threat of new technology and assuages our anxieties about the decline of human agency in a world increasingly run by machines.

Ian Fleming made Bond a modernizing hero, and the centrality of his gadgets in the films have established Bond, armed with watches capable of creating magnetic fields or Aston Martins with hidden guns, as a master of technology, a practitioner of high-tech equipment in the service of Her Majesty’s Secret Intelligence Service. But the reason why we, the audience, admire him and follow his never-ending career is to be found in his inevitable conflict with the machine.

Whatever the threat posed by the technology of the future, we are reassured by Bond’s example that one heroic individual (plus an attractive woman) can return us to normality. Bond is the man who saves the world from a nuclear holocaust by the turn of a screwdriver or pressing the right button on a control panel.

Fleming, Bond’s creator, was born at the beginning of the 20th century and was part of a generation of technological enthusiasts—optimistic young modernists who believed that the future could be transformed by new and wonderful technology. Fleming’s generation embraced the motor car and airplane, and Fleming enjoyed sports cars, cameras, guns, scuba diving, and air travel and made sure his alter ego did too.

Fleming deliberately introduced the gadgets into his stories to give them a sense of authenticity and to endorse the products he admired. He also portrayed Bond, a gentleman of a jet-setting age, as an expert in the technology of espionage, and the tools of his trade eventually became embedded into his persona. As soon as the producers of the Bond films realized that the gadgets were a major selling point to audiences, they filled each successive film with more photogenic and prescient technology. Over the years, Bond films introduced audiences to wonders such as laser beams, GPS, and biometrics well before they appeared in the real world. Producers claimed that the Bond films represented “science fact, not science fiction,” but they usually mined the latter for the latest diabolical machine that Bond had to face.

The villains’ wicked plans for world domination also reflected the changing technological threat. Fleming’s involvement in the hunt for German scientists in the dying days of World War II introduced him to chemical and biological weapons, which he considered as insidious and terrifying as the atomic bomb. He devoted a chapter of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service to a detailed account of such weapons, and the film involves deadly strains of toxins that can exterminate entire species of plants and animals. Auric Goldfinger brags that his nerve gas GB is “a more effective instrument of destruction than the hydrogen bomb.”

Fleming’s world was also changing dramatically when he started writing in the 1950s, and his enthusiasm for technology was undermined by its revolutionary effects in the business of espionage. His books were essentially an exercise in nostalgia because Bond represented a dying breed in the intelligence service—his tough guy derring-do was being replaced by the quiet work of technicians who eavesdropped on telephone calls or analyzed satellite images.

Fleming also grew very much afraid of the new weapons of mass destruction, especially an accidental or criminal nuclear explosion. And this threat was uppermost in Fleming’s mind when he pitched an idea for a Bond film: An organized crime group steals an atomic bomb from Britain and blackmails the world for its return. Eon productions took up this narrative and a nuclear holocaust hangs over Goldfinger, Thunderball, You Only Live Twice, The Spy Who Loved Me, Moonraker, Octopussy, Tomorrow Never Dies, and The World is Not Enough. The films kept up with the advance of bomb technology, from the conventional finned bombs in Thunderball to the Polaris intercontinental ballistic missiles in The Spy Who Loved Me. The menacing, cumbersome machine in Goldfinger evolves into smaller and more dangerous devices in Octopussy and The World is Not Enough, enabling “the most deadly saboteur in the history of the world—the little man with the heavy suitcase,” as Fleming wrote in Moonraker.

The Bond films would move away from the fictional villains of Fleming’s youth—the evil “others” like Fu Manchu who inspired Dr. Julius No—to smooth businessmen like Karl Stromberg in The Spy Who Loved Me. To this day, the films reflect a 1960s distrust of big business. Take Dominic Greene of Quantum of Solace, a villain who hides behind his environmentally friendly business. The faces and ethnicities of the bad guys move with the times; thus the thuggish Nazis of the early novels were replaced by more refined European industrialists in the 1970s, Latino drug kingpins in the 1980s, and Russian criminal syndicates and hackers in the 1990s.

The space race of the 1960s coincided with the first boom in Bond films, and so 007 duly moved into orbit and flew spaceships and shuttles in his fight against communists and ex-Nazis armed with nuclear-tipped missiles. Roger Moore as Bond faced the newest military technology of the 1980s—computer-based targeting systems and portable nuclear weapons—and by mid-decade he had to deal with the dark side of the digital revolution. A View to a Kill was released in 1985, a year after Apple introduced the Mac personal computer, and the film reflected the rise of the integrated circuit and its growing influence on daily life. The plot involved cornering the market for microchips by creating a natural disaster in Silicon Valley.

The second boom in the 007 franchise came in the 1990s with the success of Pierce Brosnan as a Bond who fought the bad guys in the new world of interconnectivity—the military-industrial complex of the 1960s had become the military-internet complex. In Tomorrow Never Dies the villain is no “oriental other,” but an English media tycoon. Elliot Carver is bent on world domination, not unlike the media moguls Robert Maxwell and Rupert Murdoch, for whom, as Carver points out, “words are the weapons, satellites, the new artillery.”

We love Bond because he always triumphs against the machine. No matter how futuristic and dangerous the threat, Fleming’s reliance on individual ingenuity and improvisation still wins the day. In The Spy Who Loved Me, it only takes two screwdrivers to disassemble the nuclear warhead of a Polaris missile, and it only requires a few seconds of examining a software manual to reprogram two intercontinental ballistic missile launches—the first recorded instance of one-finger typing saving the world.

Today, the fight against evil has moved into the internet and cyberspace, against malicious hackers and digitally enhanced villains, but in the end, tranquility is always restored by a hero who wrests power from the machine and puts it back into the hands of his grateful audience.

André Millard is a professor of history at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He is the author most recently of Equipping James Bond: Guns, Gadgets, and Technological Enthusiasm.

[ad_2]

Source link