ART NEWS

How Mildred Thompson’s Vibrating Canvases Envisioned Our World As It Could Be

Until recently, the vast and significant contributions Black artists have made to the history of abstraction have been under-recognized by the mainstream art world. If artists like Sam Gilliam, Jack Whitten, and Howardena Pindell are finally getting their due, thanks to big museum shows and representation at the world’s top galleries, many Black female abstractionists who began their careers in the mid-20th century such as Betty Blayton, EJ Montgomery, Mary Lovelace O’Neal, and Barbara Chase-Riboud are still awaiting such visibility.

But there have been some attempts to elevate these artists. One came in Adrienne Edward’s 2015 essay “Blackness in Abstraction” for Art in America, which became an exhibition at Pace Gallery the following year, and another in the 2017 traveling exhibition “Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today.” Curated by Erin Dziedzic and Melissa Messina for the Kemper Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, the show focused on the art-historical contributions of women artists of color and took its name from a series of works by Mildred Thompson from the ’90s.

Related Articles

Thompson’s wide-ranging oeuvre spans painting and sculpture, printmaking, musical compositions, wood works, and more. All of the late artist’s work was guided by a “natural curiosity and feeling of wanting to discover something,” Messina told ARTnews in a recent interview. “It’s bringing you into worlds that you’ve never seen before—things that are invisible to the naked eye.”

It’s only in the years since the “Magnetic Fields” exhibition that Thompson’s art has begun to be shown with relative frequency. Her estate is now represented by New York’s Galerie Lelong & Co., which has mounted two solo shows dedicated to work by Thompson, who died of cancer in 2003. Major institutions in the South such as the SCAD Museum of Art, the New Orleans Museum of Art, and the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art have showcased her work, and Thompson’s paintings were included in the acclaimed 2018 Berlin Biennale. In 2021, her art appeared in the exhibition “The Dirty South: Contemporary Art, Material Culture, and the Sonic Impulse” at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, curated by Valerie Cassel Oliver.

Messina, who is curator of Thompson’s estate and a former student of the artist, said that Thompson was ahead of her time—which is why her work is hard to classify. “She wouldn’t be put in a box,” Messina said. “She wouldn’t stick to one thing. She was always letting the idea let her lead her to the best medium for that idea.”

Mildred Thompson with a free-standing wood assemblage.

©Estate of Mildred Thompson/Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Early Career

Born in 1936 in Jacksonville, Florida, Thompson was was a precocious child growing up, always curious about how things worked. She once took apart a bicycle and then put it back together, to learn more about its construction. In the mid-1950s, she left Florida to attend Howard University in Washington, D.C., where she got her first formal training in art making in the school’s legendary art department, which had produced other luminary artists like Alma Thomas and Loïs Mailou Jones. One of her mentors at Howard was the department’s chair, James A. Porter, who helped arrange for her to receive a scholarship for a summer study at the Skowhegan School in Maine.

After graduating from Howard in 1957, she received a Max Beckmann Scholarship to study at the Brooklyn Museum School in New York. While there, she learned about the Fulbright Program and decided that she wanted to live abroad to further her artistic education. When she didn’t receive a Fulbright, Thompson, who felt she was more than qualified, was nevertheless undeterred. “I decided to go to Europe on my own,” she wrote in a 1977 essay about her career for Black Art: An International Quarterly. “Anyone could buy a boat ticket. I could pay my own way somehow—I was determined to go.”

Thompson saved up money to sail to Europe through a summer teaching job at Florida A&M University Tallahassee. She had recently met artist and art historian Samella Lewis, who was the school’s art department chair and would become a lifelong friend and mentor to Thompson. Though she initially thought she might travel to Paris, Thompson’s other mentor, Porter, encouraged her to consider West Germany, given the parallels he saw between Expressionist art of the 1910s and ’20s and her early paintings.

Though she initially had trouble adjusting to Hamburg, Thompson eventually enrolled in the city’s Hochschule für bildende Künst, where she was encouraged to continue making her abstractions. She soon had her first solo show in 1960 at a Hamburg gallery, and several of the works sold. The exhibition later led to a summer residency at a castle in Italy, sponsored by American arts patron Caresse Crosby.

Mildred Thompson, Wood Picture, ca. 1967.

©Estate of Mildred Thompson/Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

From West Germany to New York and Back Again

In 1961, Thompson decided she had learned as much as she could at Hamburg’s Hochschule and returned to New York. She was quickly able to sell two prints to the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and two prints and a drawing to the Brooklyn Museum, but she could not find a commercial art gallery that would represent her. (Such was the case for many women and Black artists of the era.) In her Black Art essay, Thompson recalled that one art dealer “said—being helpful—that it would be better if I had a white friend to take my work around, someone to pass as Mildred Thompson.”

Mildred Thompson, Wood Picture, ca. 1972.

Photo: Roman Alokhin/©Estate of Mildred Thompson/Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York/New Orleans Museum of Art

Though Thompson’s New York stay was been difficult for the artist emotionally and mentally, it ended up spurring a body of work that she would continue for the rest of her career. Inspiration struck in the form of slats and repurposed vegetable crates that she found in New York’s Lower East Side neighborhood, where she was living at the time. “She was looking around at any materials that she could use that really struck her,” Messina said.

She stayed in New York for two more years and spent both summers at the prestigious MacDowell Colony in New Hampshire. But by 1963, Thompson decided she had had enough of New York and returned to West Germany. She eventually settled in the town of Düren, not far from Cologne, and stayed for some 13 years. As Lowery Stokes Sims wrote in an essay for a 2018 Galerie Lelong & Co. show, “Thompson’s wanderlust was not merely one of personal predilection; her decision to spend extended periods in Europe was made partly in response to the discouragement and discrimination she faced while trying to establish her career in New York City.”

In West Germany, Thompson was able to set up a studio, and she dedicated herself to perfecting her use of wood. These elegant pieces bridge the gap between painting and sculpture. In one from 1972 (now in NOMA’s collection), Thompson displays the beauty of the light wood grain in nearly even and symmetrical vertical strips, until that harmony is interrupted by a sharp purple triangle. “You see an intuition turn into real craftsmanship,” Messina said.

Mildred Thompson, Untitled, 1969.

©Estate of Mildred Thompson/Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

Scientific and Cosmological Inspirations

In addition to her work in wood, Thompson was equally dedicated to making oil paintings, works on paper, and etchings. For these works she drew on an even wider set of references, including the work of artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Paul Klee, Theosophy (a religion whose followers included Kandinsky, Hilma af Klint, and Piet Mondrian), music, and science—in particular, physics. Hers became a practice that was dedicated to making the invisible visible. “At the root of all of her ideas was this universal resonance and these patterns that we all see in ourselves and in the world around us,” Messina said. “She felt like that connectivity is what made us all sort of beings on a planet together.”

After years spent in West Germany, Thompson moved back to the United States in 1974, when she became artist-in-residence for Tampa Bay-Hillsborough County. Then, in 1977, she moved back to D.C. for a residency at Howard. Thompson stayed in D.C. until 1985, but beginning in 1981, she was also splitting her time between the U.S. capital and Paris. In her 1977 Black Art essay, Thompson said she was convinced to return to the United States because people were telling her how much it had changed. In it she seems hopeful: “America HAS changed. I am ready now for America and am eager to see if America is really ready for me.”

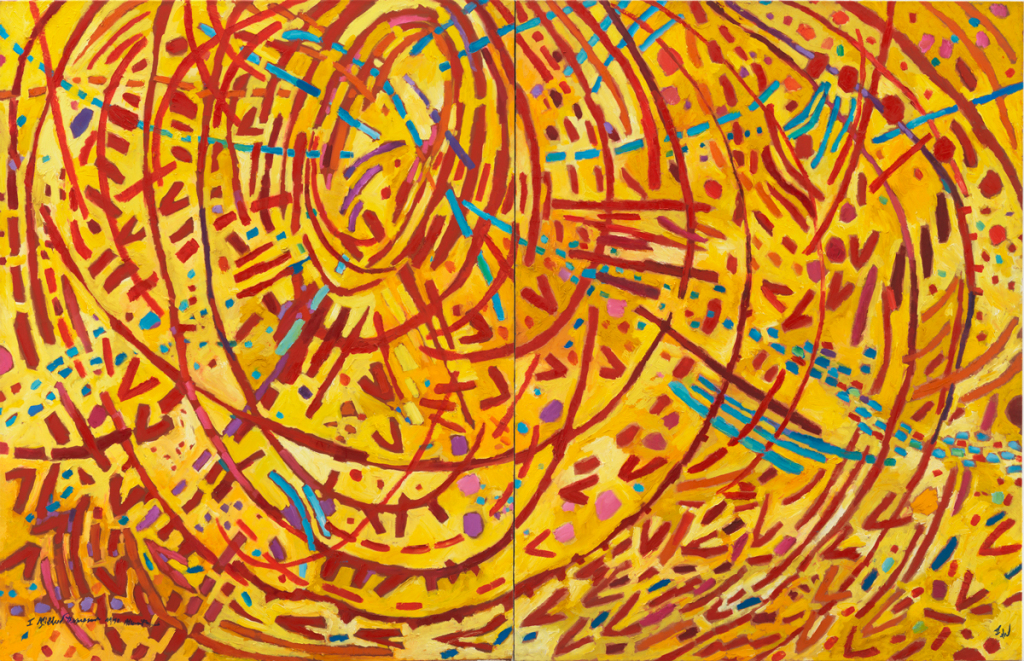

It was in Paris that Thompson began to paint abstract canvases, beginning with her 1980s series “Rebirth of Life.” In these modestly sized canvases, thick layers of paint form complex abstract shapes in bright colors. In one from 1983, a mostly yellow background is filled with dots of pink, sky blue, and green, and contorting shapes appear in red and orange tones. The effect is one of a composition pulsing with life.

Mildred Thompson, String Theory 11, 1999.

©Estate of Mildred Thompson/Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York/Johnson Collection

Vibrating Colors

Around 1986, Thompson decided that she would end her years-long self-imposed exile in Europe and live in the U.S. permanently. She settled in Atlanta, where she taught at Spelman College, Agnes Scott College, and the Atlanta College of Art (now part of the Savannah College of Art and Design). In addition to the generations of students she taught, for over a decade beginning in the late 1980s, Thompson was also an associate editor for Art Papers magazine, where she interviewed artists like Emma Amos, Valerie Maynard, Loïs Mailou Jones, Guillermo Gomez-Peña, and Meredith Monk.

In a large studio with 20-foot-tall ceilings, Thompson was now able to create art on a much larger scale. The paintings she made in Atlanta were informed by color theory—she juxtaposed contrasting and complementary hues with each other to ensure that the canvases popped. In her famed “Magnetic Fields” series (1990), Thompson considered the theory that magnetic waves were yellow when seen on an ultraviolet scale. In these paintings, large expanses of yellow become host to radiating spirals of reds and turquoise. Meanwhile, with her contemporaneous “Radiation Exploration” series (1994), blue dominates, in homage to the color that radiation waves emit when seen on an ultraviolet scale.

“She wanted the work to be joyful and energetic,” Messina said. “She understood how we as humans stand before a large-scale painting and feel color—the way it vibrates, the way we internalize it…. You’re having a physiological response when you’re looking at her paintings, as well as a psychological one.”

Mildred Thompson, Radiation Explorations 8, 1994.

©Estate of Mildred Thompson/Courtesy Galerie Lelong & Co., New York

‘Everything I Touch Will Be Part Black and Female’

Though Thompson dedicated herself to abstraction for much of her career, she experimented with figuration, most notably in the illustrations that accompanied Audre Lorde’s poems for a collaborative sketchbook titled Journey Stones: Love Poems. (Lorde and Thompson were romantically involved at the time, and Thompson’s drawings for this series, which date to ca. 1977–78, were included in the acclaimed traveling 2019 exhibition “Art after Stonewall, 1969–1989.”) In these sketches, Thompson tenderly depicts the love between Black lesbians, who are shown in the nude, hugging and caressing each other.

Her abstractions stand apart from these works because they don’t appear overtly political—and Thompson faced adversity for this. Thompson countered those arguments frequently in essays she wrote, suggesting that her identity was intimately connected to her art, no matter what its subject was. In one catalogue essay from 1980, written shortly after she had abandoned figuration, she said, “With art, there are symbolic things that have to be learned to make work universal … you can’t limit who you communicate with. … But (first) you have to know yourself. Everything I touch will be part Black and female—all my success and the things I have gotten are part of that.”