ART NEWS

Eight Spots in the United States Where You Can See Petroglyphs | Travel

[ad_1]

Finding petroglyphs (rock carvings) and pictographs (rock paintings) in the United States has never really been that hard. Petroglyph National Monument in Albuquerque boasts more than 25,000 images—mostly humans, animals and tribal symbols—carved into volcanic rocks by Native Americans and Spanish settlers 400 to 700 years ago, and another obvious site, Canyonlands National Park in southeastern Utah, is famously known for life-size human figures and depictions of men fighting, painted between 900 and 2,000 years ago.

“We look at these images and symbols from people who traveled through the Rio Grande Valley hundreds and even thousands of years ago, yet they seem so distant that it is easy to think that they don’t matter,” says Susanna Villanueva, a park ranger at Petroglyph National Monument. “But when you hike along the trail and stand in front of a boulder with petroglyphs, you realize that this used to be their world and it was just as alive to them as ours is to us. The Ancestors graciously reach out to us across centuries through these petroglyphs to remind us that they do matter and that they are still connected to this world, to this landscape, and to us, for eternity.”

And while we may naturally think of petroglyphs and pictographs being out west, in reality, they are found in more than half of our country’s states and territories—meaning you don’t have to travel far at all to get a glimpse of native history.

These eight sites have ancient petroglyphs in locations that might surprise you.

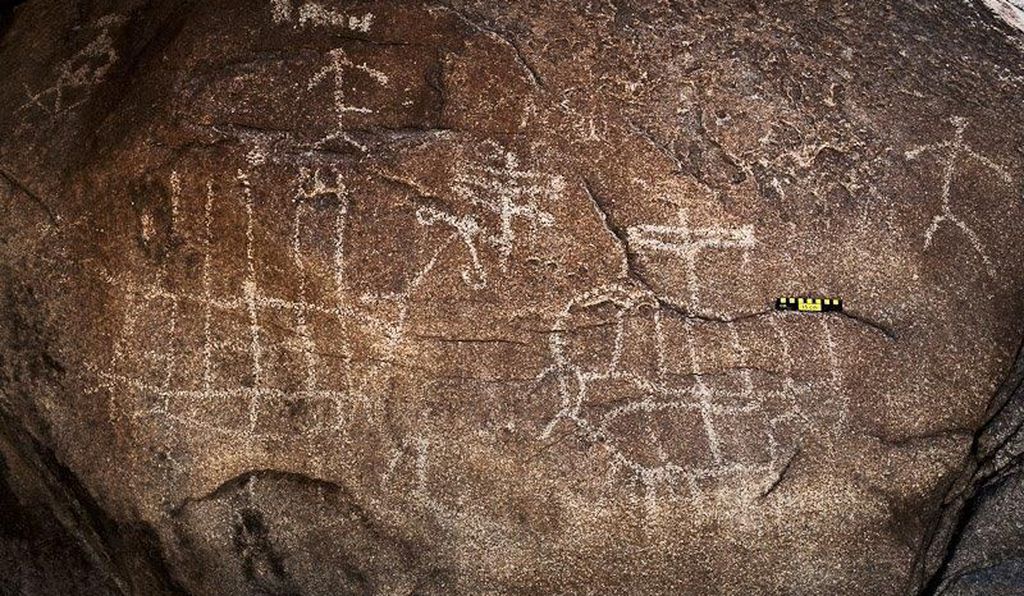

Spanish Ship; East County, San Diego

(Ted Walton)

Somewhere in a location undisclosed by the people who discovered it, east of San Diego, a boulder carries possibly the oldest graphic representation of a recorded event in U.S. history. In 1542, Spanish explorer Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo sailed the San Salvador to today’s California, discovering what would become San Diego. The ship was the first recorded European vessel to survey the coast of southern California. The indigenous Kumeyaay people who lived in present-day San Diego County for thousands of years recorded the event by carving an image of the ship into the rock. There’s an exact replica of the boulder at the Maritime Museum of San Diego, as part of the San Salvador exhibit.

Petroglyph Beach State Historic Park; Wrangell, Alaska

(Creative Commons by gillfoto)

About 40 petroglyphs are on boulders scattered across Petroglyph Beach in Wrangell, Alaska—the highest concentration in the state’s southeast. No one knows exactly why the petroglyphs are there or what they mean, but locals believe they were carved thousands of years ago by the indigenous Tlingit, who have a strong presence on Wrangell Island. Most of the petroglyphs, discovered in the 1800s, depict spirals, faces and birds, though there’s one distinctive carving of a whale by the park’s interpretive center. The area was designated a state historic park in 2000, and visitors are welcome to take rock rubbings of replica petroglyphs at the interpretive center.

Dighton Rock State Park; Berkley, Massachussetts

(US Public Domain)

Dighton Rock is shrouded in mystery. The 40-ton boulder (now in a small museum in the state park) sat half-submerged in the Taunton River right at Assonet Neck, where it widens to Mount Hope Bay and the ocean, until 1963. The inscription of various geometric patterns, lines and human shapes faced the sea. Dighton Rock first entered recorded history in 1680 when local reverend John Danforth made a drawing of a portion of its carvings—that drawing can be seen in The Royal Society’s online picture library. Cotton Mather found the rock in 1690, describing it in his book, The Wonderful Works of God Commemorated, as being “filled with strange characters.” Since then, there have been many speculations as to the origins of the carvings. Some theorize that ancient indigenous populations carved it to depict Carthaginians consulting an oracle that would tell them when to sail home. Others surmised it was carved during King Solomon’s reign as a voyage map and described in the Old Testament, or that it depicted a Portuguese journey in 1511. Still others believed it to be a warning to anyone about to enter the river, or the ancient Hebrew words “king,” “priest” and “idol.”

Sanilac Petroglyphs Historic State Park; Cass City, Michigan

(Creative Commons by ClaytonIlibrar)

The Sanilac Petroglyphs are the largest collection of rock art in Michigan. They were discovered in 1881 after a massive wildfire destroyed everything in the area—including the grass and brush that was covering the sandstone rock. Local Anishinabek people carved the etchings sometime in the last 1,400 years in what is now considered a holy site, documenting the creation stories, daily life, history and seasonal events of the Anishinabek. A few years ago, the petroglyphs were vandalized; now, Michigan’s Department of Transportation, State Historic Preservation Office and Department of Natural Resources are working with the Saginaw Chippewa Indian Tribe of Michigan to preserve the carvings, measuring them with lasers and creating digital models of the more than 100 petroglyphs at the site.

Judaculla Rock; Cullowhee, North Carolina

(Creative Commons by QueenOfFrogs)

With 1,548 carvings on one soapstone boulder, Judaculla Rock has more carvings on one rock than anywhere else in the eastern United States. It’s not known for sure what the images, carved between 500 and 1700 mean, but some local historians say the more recent ones depict a map of local resources and game. Otherwise, the local Cherokee tie the boulder in very deeply with the legend of a giant named Tsu’kalu. The legend says that he wanted a wife, so he took a woman from a local Cherokee tribe and brought her into the spirit world. The woman’s mother and brother wanted her back, though, so they went to fast for seven days outside the cave entrance to the spirit world in order to see her. Her brother broke the fast after only six days, and Tsu’kala reentered the physical world—through Judaculla Rock—to punish him. Tsu’kala killed the brother with lightning, and the woman was so distraught that she wanted to return to the physical world, but Tsu’kala wouldn’t let her. Instead, he made a deal with the Cherokee to allow them to have eternal life in the spirit world after death. The carvings are believed to be directions on how to enter the spirit world.

Reef Bay Trail, U.S. Virgin Islands

(Flickr, by Molly Stevens)

In what is the U.S. Virgin Islands today, the Taino civilization flourished from 900 to the 1490s. The Taino left their mark at the base of the tallest waterfall in St. John’s Reef Bay: petroglyphs of faces carved into blue basalt rock, in a space stretching about 20 feet, and some carvings spilling onto other rock faces nearby. The faces in the petroglyphs match faces found on Taino pottery found at other sites, but these etchings have a more political reason for existence. The Taino carved the faces where the chief’s ancestral deities gathered, representing those ancestors. They were meant to help the people communicate with the spirit world, and also to change the religious narrative at the time, from one where everyone was more or less equal to a narrative encouraging the emergence of a group of social religious elite who would control all the Taino in the area.

Roche-a-Cri State Park; Friendship, Wisconsin

(Creative Commons by Royalbroil)

For the most part, glaciers moving through Wisconsin during the last Ice Age flattened the landscape. However, a giant stone mound pushing 300 feet up from the otherwise level terrain remained. Since before 900, people living in the area have used the geological feature, called Roche-a-Cri Mound, to inscribe symbols, grafitti and art. Roche-a-Cri has ancient pictographs from the ancestors of the local Ho-Chunk, who carved arrows, birds, figures, canoes and more into the rock, and used it to track astronomical events and local life. In the 1860s, European settlers graffitied the rock by carving their names into it—most notably the very visible inscription, “A.V. DEAN. N.Y. 1861.” In that same year, the military bore history into the rock, with round indentations left by Company D of the Wisconsin 1st Cavalry Sharpshooters; they camped there and used the rock for target practice.

Jeffers Petroglyphs; Comfrey, Minnesota

(Flickr, by minnemom)

Jeffers Petroglyphs is the largest collection of rock carvings in one place in the Midwest. The site has about 8,000 petroglyphs, and they’re sacred for many of the local indigenous tribes, like the Dakota, Cheyenne, Arapaho, Iowa and Ojibwe. They’re truly ancient as well, with the earliest carvings dating back to 9,000 B.C. The most recent was carved in the 1700s. The earlier petroglyphs are almost exclusively animals, even including a baby moose from about 8,000 B.C. Human figures participating in ceremonies joined the animals around 3,000 B.C. Some of the others depict spirits, prayers and altars. Native American tribes have been coming to Jeffers for centuries to do ceremonial work, fast, pray and teach lessons to children through the artwork. Today, it’s still considered a sacred worship space.

[ad_2]

Source link