ART NEWS

Corporate Photography Reveals a Dehumanizing Gaze

When it comes to art of the anthropocene, we are often shown the wound and not the assailant. The discourse around ecological crises—and the artistic interventions meant to call attention to them—has primarily been concerned with how to frame their enormous scale. As such, philosopher Timothy Morton’s concept of “hyperobjects”—phenomena which defy our understanding as they exist across such huge swaths of time and space—is useful for capturing the communication failures surrounding climate change. Instead, the framing of accountability might be a more pressing question. Audiences have absorbed images of destruction for years, but what they haven’t seen is who is responsible for all of these crises.

Related Articles

Identifying the malefactors is difficult work. Company men don’t hold the smoking gun. They do not start fires with their own hands as they profit from the burning. Yet, as the Latin expression qui facit per alium facit per se has it, he who does a thing by the agency of another does it himself. This diffusion of agency makes it hard to represent accountability visually. That which is not seen is not easily otherwise sensed. Photographer Richard Mosse, in his series Tristes Tropiques, and—separately—Latin America scholars Kevin Coleman and Daniel James, in their book Capitalism and the Camera, offer a scintillating alternative. By probing the imaging technologies used by corporations, we might come to better understand the gaze of the prospectors who benefit from ecological and political harm.

The destructive function of the human gaze seems to be a self-evident fact. Desire for experiences and things drives consumption, turning the wheel of unsustainable extraction at an exponential pace. “Capitalist consumption is a key factor driving global warming,” Kevin Coleman and Daniel James point out in the introductory essay to Capitalism and the Camera, which attempts to explain how driving traffic to certain images, products, and activities is the result of a hidden profit motive. “The circulation of images, in turn, drives consumption. The desire to have a certain way of life is curiously first an image and only second a reality.” As easy as it is to shudder at the collective consumptive power of the masses, Coleman and James ask us instead to consider the primary destructive gaze of powerful companies.

An example from the United Fruit Company’s archives detailing the effects of fertilizer applications. Honduras, 1953

United Fruit Company

Coleman and James point to the massive photo archives of multinational corporations as a valuable resource that reveals how photography has been an essential tool in penetrating frontiers of capital accumulation. In reference to the United Fruit Company’s collection of 10,400 images held at Harvard University, the authors write, “Here we find that the company used photography to present its work to shareholders and to the public, to control nature at a distance, to scientifically analyze the ripening of bananas and the spread of disease, to convert biodiverse tropical forests into monocrop plantations, and to monitor the health and productivity of its workers.”

The photographs document each building in the United Fruit Company’s Honduras plantation, aerial views of the land, workers, banana trees, and the social lives of the American expats who lived there. At first glance, the photos seem too opaque to glean the kind of information Coleman and James describe. A picture of the jungle reveals what? But between photos of ice cream socials and blurry leaves, clarity emerges in the thicket of the enormous archive. One photo, Figure XVII from 1953, shows some neat rows of banana trees, a man standing to the right in the shade of some lush fronds. The photo is captioned, “Typical leveled area approximately seven months after applying 550 pounds of nitrogen per acre, sixteen months after planting, shows vigorous growth in contrast to that shown in Figure XVII.” Another photo documents the advancement of pestilent red rust thrips across the skins of bananas.

The archive shows us that the local environment and workers were observed as exploitable materials, each photograph a data point to be responded to and molded. Meanwhile, the shining smiles of expats at yet another cookout or their sweaty bodies dressed up for a day of tennis show how they were treated as subjects worthy of respect, consideration, and affectionate attention. The lives of the Hondurans and the complexity of their ecology were not meant to be represented as full subjects because they were never meant to be treated that way.

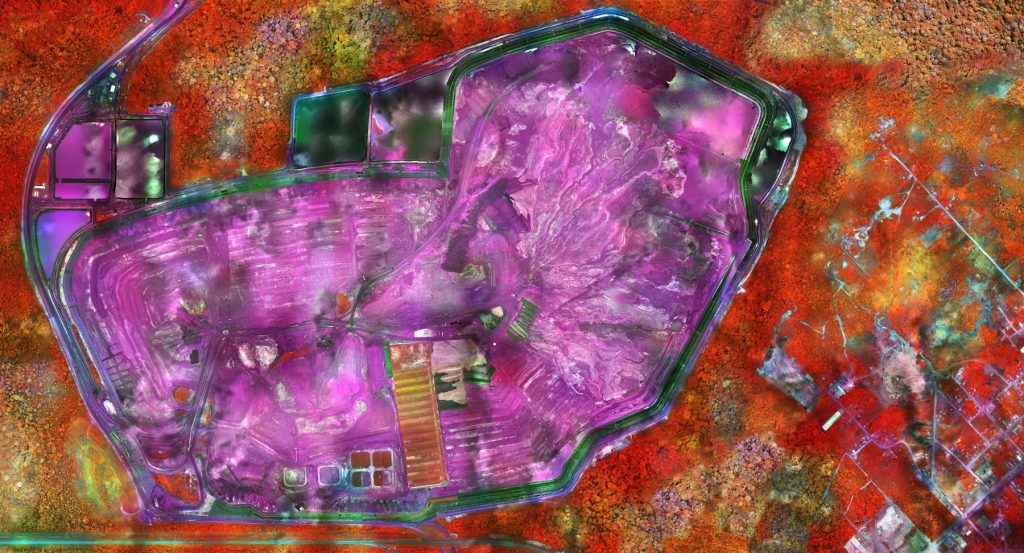

Richard Mosse’s work advances our understanding of the gaze of the powerful by appropriating the imaging technology used by corporations and government entities in their pursuit of capital gains and border enforcement. In a recent exhibition at Jack Shainman Gallery in New York and now at Fondazione Mast in Bologna, Italy, images from Mosse’s series “Tristes Tropiques” appropriates the data rich photography used by corporations and scientists to depict the various ecological crimes playing out across Brazil, including the attention-grabbing fires of 2020. Mosse used geographic imaging system (GIS) technologies, drones, and multispectral imaging to capture large topographic images of destruction colored in rich hues. Depictions of mining, intensive feedlots, illegal timber production, and the path of intentionally set fires are seen as complex scientific images, showing us something sickly. Cutting-edge technology, which Mosse says is used by both scientists and the “bad guys,” allows us to see things we typically couldn’t, especially not from afar—the health of plant life, heat signatures, chemical analysis, PH measurements.

Richard Mosse, still from Incoming, 2016

Mosse has always had an interest in photographic innovations, especially those developed by the military. When documenting the Congo in his 2011 series “Infra,” he used Kodak’s now discontinued Aerochrome film. Developed by the US military during World War II, Aerochrome could be used to detect camouflaged military movement by reconnaissance planes, as the infrared-sensitive film would highlight plant material that gave off infrared light but not the inorganic greens of camo. Mosse would again turn to military grade technology for his film installation Incoming, which documented migrations playing out in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa between 2014 and 2016. This time, he would use a surveillance camera that can detect body heat from great distances, hence its primary use in border enforcement. The images are ghostly, horrifying, and not meant for public messaging, though they could make unintended fodder for conservative news platforms. Yet it is through such extreme, almost monstrous representations that soldiers are taught to see migrants. Similarly, it is through the more abstracted, neon-hued, GIS maps of forests that prospectors decide where to plunder for oil and minerals with little consideration of the lives contained within.

But this where other artistic interventions intercept this obliterating gaze. For example, in the graphic memoir of Pablo Fajardo, Crude, the influential Ecuadorian lawyer who fought against a Chevron oil spill in the Amazon, the illustrator Damien Roudeau helped bring a hidden history into view. Fajardo describes the first moments that Indigenous peoples in the Ecuadorian Amazon first came into contact with Chevron, when a huge metal bird was spotted in the territory of the Cofán people. Roudeau depicts the scouting helicopter, which was probably fitted with the kinds of imaging technology used by Mosse, breaking through the canopy.

By the end of Chevron’s oil mining stint, two Indigenous tribes, the Tetete and the Taegiri, would be pushed to extinction, and countless others died from cancer and other health issues caused by drinking, bathing, and cooking with water soiled by 16 million gallons of oil and another 18.5 million gallons of chemicals. Not to mention the ruination of a primary forest that has yet to receive the billions of dollars of clean-up funds that Chevron owes them. Roudeau’s sketch-like illustrations, layered with watercolors, often blur the line between the vibrancy of the forest and the oil that skims its surfaces, displaying the insidious intermingling of poison and life. If Roudeau’s illustrations work to illuminate the hidden externalities of resource extraction, Mosse’s photographs remind us that all the death that follows the ravaging hand of capital is ultimately reduced to abstraction for those of us who benefit, if distantly and unwillingly, from the exploitation of resources, product, and profit.

Excerpt from activist Pablo Fajardo’s graphic memoir Crude, 2020, illustrated by Damien Roudeau.