ART NEWS

Barry Le Va, Artist Who Pushed the Boundaries of Sculpture, Has Died at 79

Barry Le Va, a sculptor whose visually seductive installations often involved subjecting his materials to unseen systems that resulted in their destruction, has died. New York’s David Nolan Gallery, which represents Le Va, said that the artist died on Sunday at 79 but did not state a cause of death.

Le Va became part of the New York art scene during the late 1960s and went on to be associated with the Process art and Post-Minimalist movements. Unlike the best known adherents of those movements, including Richard Serra, Bruce Nauman, and Robert Morris, Le Va has remained a somewhat obscure figure, no doubt in part because his work is so formally rigorous and can be difficult to parse. But he has a set of devoted fans that include artists, critics, and historians spanning multiple generations.

Related Articles

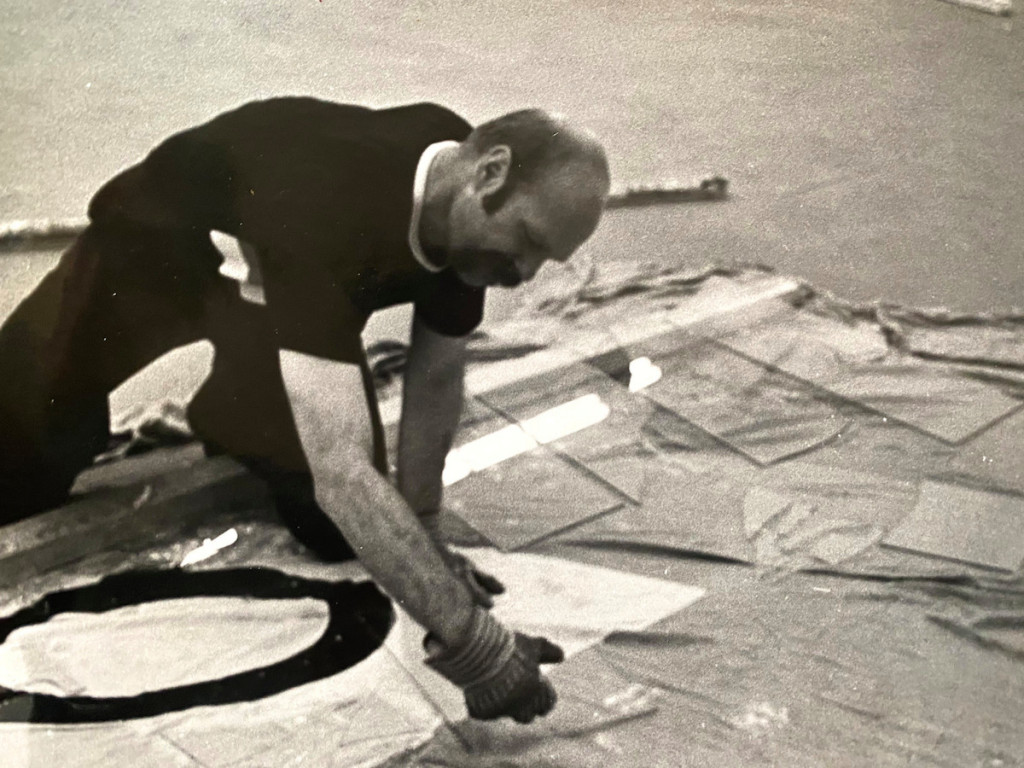

Among Le Va’s most famous works are those from the ’60s made using felt and other industrial materials. In these works, rolls of felt are cut into smaller pieces, the tiny, uneven clippings strewn about across a gallery space. The pieces seem, at first glance, to be random. In fact, Le Va sketched them out in advance, using diagrams to map out where and how the felt would be arrayed.

Many have likened these works to Jackson Pollock’s all-over abstractions, in which drips and drabs of paint are flung across large canvases. The felt, some critics have said, could be likened to Pollock’s paint, and the floor to the Abstract Expressionist’s canvas. Le Va argued against that interpretation, however.

“People didn’t know how to deal with that kind of work yet, they could only view it in the context of what they knew,” Le Va said in a 1997 Bomb interview. “If it was a painting on the floor, they could address it in terms of balance and composition. But if it’s sculpture all over the floor, was it really sculpture, or what was it?”

Courtesy David Nolan Gallery/National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

The felt pieces, now considered emblematic of a style known as a scatter art, also thrill because they could be changed so easily—one wrong step, and a viewer has upended the piece’s composition. Their fragility is mirrored in some of Le Va’s other works. In his chalk pieces, for example, he created environments by blowing his materials around a room, creating patterns resembling those left behind on a shore by crashing waves. As alluring as they are, the chalk works are also stony, even forbidding—viewers know that, if they step on the piece, the whole thing is disturbed, and it stops looking so beautiful. By this logic, the work bars entry from a space, and the viewer is only left to look at it from a distance.

A similar sensibility undergirded Le Va’s 1968 work Omitted Section of a Section Omitted, which appeared in the 1969 Whitney Museum show “Anti-Illusion: Procedures/Materials.” For that work, the artist dusted flour onto a gallery floor, creating a ghostly triangular form that would be easier to destroy than it was to produce.

A latent form of violence exists in all this, too—perhaps a reference to the tensions boiling over, both in the U.S. and abroad, as critic Roberta Smith suggested in her New York Times review of Le Va’s 1990 retrospective at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, New York. (The show had been organized by the Carnegie Mellon Art Gallery in Pittsburgh.) For his “Cleaver” series, Le Va flung giant knives into walls and floors, and for another series, he would pile up sheets of glass and smash into them, sending shards flying. Yet the physical processes that led to these objects’ making was concealed, and viewers were left to imagine how it all went down.

Le Va, for his part, dismissed the idea that these works were in any way violent. “I thought of it in terms of architecture, the acoustics of the space, materials making up the space, floors, walls, physical activity, time, stereo sound, the mathematics of a specific space: information present through sound,” he said in his Bomb interview. “Let me describe it as procedure—a procedure someone must absolutely adhere to.”

Courtesy David Nolan Gallery

Barry Le Va was born in 1941 in Long Beach, California. He went on to attend the Otis Art Institute in Los Angeles for his M.F.A., having studied architecture and math as an undergraduate at California State University in Long Beach. His concern, almost from the very beginning, was the relationship between the viewer and an art object. When he was a student, he wrote himself a note that read, “How could one deal with what sculpture does to the physical body of the viewer, without making an object?”

Artforum magazine, founded in 1962, was integral in bringing him to the attention of the art world as it existed beyond the confines of California. In 1968, before he had even turned 30, Le Va’s work appeared on the cover of that magazine, marking a significant entrée that was rare at the time for what would now be termed an emerging artist. In the article accompanying it, Jane Livingston, who was then a curator at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, wrote, “Within a two and a half year period, from early 1966 to the present, Barry Le Va’s art has traced out a personal stylistic history of extraordinary repleteness. If his assumptions and terms are problematical and sometimes difficult to accept, they are eminently worth examining.”

Le Va’s rise was swift. He showed his sculptures and conceptual pieces at New York’s esteemed Bykert Gallery during the ’70s, and he appeared in the 1970 Museum of Modern Art exhibition “Information,” which is credited with having helped to define Conceptualism as an art movement. He also showed at three editions of the Whitney Annual and its successor, the Whitney Biennial; three editions of Documenta, the touted quinquennial held in Kassel, Germany; and the 2015 edition of MoMA PS1’s recurring “Greater New York” survey. A 2005 Le Va survey organized by the Institute of Contemporary Art Philadelphia received acclaim, and a current show of his art is nearing the end of its run at the Dia:Beacon museum in Upstate New York.

Although Le Va is often called a sculptor, he resisted that label. “Maybe sculpture is only there in the sense of a word,” he said in the Bomb interview. “It’s useful and useless at the same time. It means nothing.”