ART NEWS

ADÁL, Key Photographer Whose Work Imagined New Futures for Puerto Rico, Has Died at 72

Adál Maldonado, a key Puerto Rican artist who went by ADÁL, has died of pancreatic cancer at age 72. His passing was confirmed by Taína Caragol, a close friend and a curator at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Over some 45 years, ADÁL created a wide-ranging and experimental artistic practice that included portraits documenting important Puerto Rican artists, performers, and intellectuals and extended to projects in which he imagined new futures for Puerto Ricans that would lead to liberation and self-determination.

Deborah Cullen, who most recently served as a director of the Bronx Museum of Arts, said, “ADÁL created numerous notable bodies of work, including musical performances and complex installations, but his photo series—by turns beautiful, moving, and bitingly funny—form the backbone of his contribution. His brilliant work addresses the complexity of Puerto Rican identity, its political status, its history and its rich folk expressions, and the conflicted position of the Puerto Rican diaspora in New York.”

ADÁL, Antonio Lopez, 1943 – 1987, from “Portraits of the Puerto Rican Experience,” 1984.

©1984 Adál/National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Among those who sat for his pictures were Antonio Lopez, Clemente Soto Vélez, Pedro Pietri, Marc Anthony, Rita Moreno, and Tito Puente. First begun in the 1980s, they were later used in the social studies curriculum in the New York City Public School System.

The exquisite images, 20 of which were acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2014, each have their own personality and style that seems to embody the sitter. Lopez clutches the rail of a step ladder next to one of his wall-size illustrations; Anthony looks upward arms raised; Pietri in a tuxedo T-shirt laughs as he stands in front of a cross and next to a sign attributed to Reverend Penro that reads, “I cannot save your soul with religion. I can save your life with a condom.”

This series powerfully asserted the importance of Puerto Ricans within the history of United States, though ADÁL’s work often broached other issues as well. In 1994, as part of “El Puerto Rico Embassy,” a multidisciplinary conceptual project that was a collaboration the late Nuyorican poet Pedro Pietri, he created a series titled “El Puerto Rican Passport, El Spirit Republic de Puerto Rico” that appear as passports and is accompanied by a four-page manifesto, subtitled “Notes on EL PUERTO RICAN EMBASSY.”

In a 2014 interview with the Smithsonian American Art Museum, on the occasion of two of the work’s inclusion in E. Carmen Ramo’s acclaimed “Our America: The Latino Presence in American Art” exhibition at SAAM, ADÁL expanded on his motivations behind the work, which he saw as a way for Puerto Ricans in the diaspora to “self-realize themselves”: “I initially was thinking about how el puertorriqueño (the Puerto Rican) reaffirms his identity outside of Puerto Rico, so we felt that as part of that process we could invent a new ritual, a ritual that could substitute the old rituals and traditions.”

ADÁL, El Puerto Rican Passport, El Spirit Republic de Puerto Rico: Adál Maldonado, 1994

©2012 ADÁL/Smithsonian American Art Museum

The way ADÁL formatted the passport also spoke to his broader aims as both an artist and activist. The passport images, typically crystal-clear head-on portraits of unsmiling people meant to easily identify them, are blurred, making the sitter unidentifiable. Additionally, the text ADÁL wrote to accompany the passports, itself a satire of the language typically printed on such official documents, appears in Spanglish.

“He was constantly playing, but he had very serious things to say,” Caragol said, adding, “It was a creative project for an imaginary land where creativity and art were the forces that freed Puerto Rico from its colonial relationship to the U.S.”

Francisco Rovira Rullán, a director at Roberto Paradise Gallery in San Juan, which represents the artist’s estate, said, “ADÁL is one of those artists you cannot copy, context oriented, a community builder, his work is vast, complex, a figure whose importance will be ever-growing.”

In the series “Coconauts in Space,” begun in 1994 and continued through 2016 when he received a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship that gave him access to NASA’s archives held by the National Air and Space Museum, ADÁL reimagines the first moon landing. In the artist’s hands, it is not a mission led by the United States in 1969 but a journey in 1963 by Puerto Rican astronauts. In a series of 20 photographs printed on 20-by-20-inch metal plates, we see the story of Comandante ADÁL’s trip from a spaceship hurling through space to the landing pod’s approach to Comandante ADÁL’s first steps on the moon, where he ultimately plants a Puerto Rican flag before returning to Earth via a water landing.

The series, which was accompanied by a related 10-minute video titled Coconauta Interrogation/Air Intelligence Center, appeared in the lauded 2017 exhibition “Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas,” which opened at the UCR ARTSblock in Riverside, California, as part of the Getty Foundation’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, and later traveled to the Queens Museum.

In an email to ARTnews, one of the show’s curators, Robb Hernández, said that the artist “found a way to make one reality reflect on another,” adding that by “proposing the ‘coconaut’ as the precursory space traveler unseating the U.S. space program to reimagine the moon landing anew, his unique combination of humor and speculation mobilizes his work into something more than postmodern irony and conceptual photography.”

ADÁL, from “Coconauts in Space,” 1994–2016.

©Adál

Adál Maldonado was born in 1948 in Utuado, Puerto Rico. He moved to New York at the age of 17, and then to San Francisco in the 1970s to study at the San Francisco Art Institute, where he established lifelong friendships with the Bay Area’s Chicanx artists, including Esther Hernandez and Rupert García. It was during his time at SFAI that visiting photographer Lisette Model encouraged him to go by a single name—and ADÁL was born. By the end of the decade, ADÁL returned to New York, where he immersed himself in a cohort of Nuyorican artists.

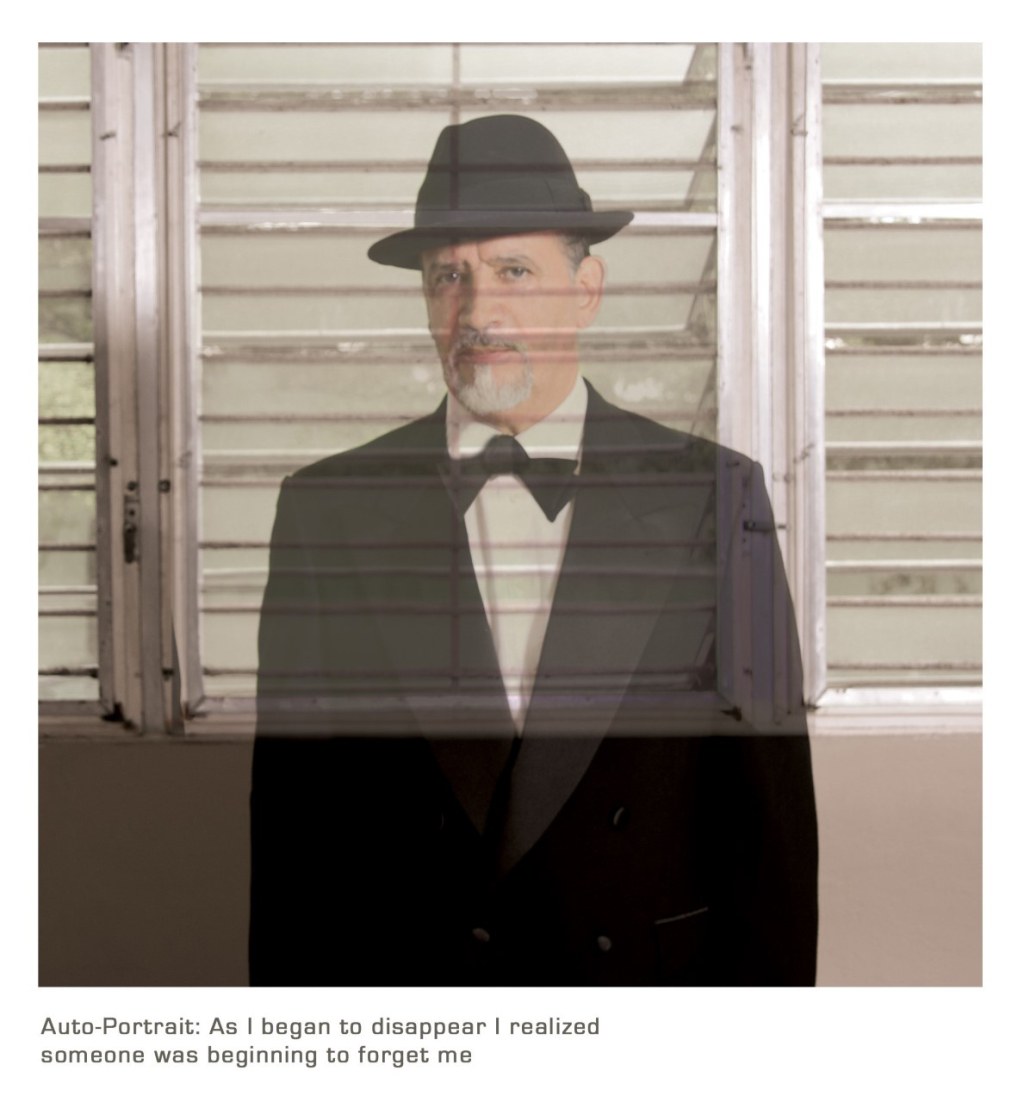

But ADÁL also turned the camera on himself, creating a surreal, beautiful group of self-portraits that meditate on the fleetingness of life and the complexities of one’s inner self.

ADÁL, Un Momento Retardado (A Suspended Moment), ca. 1973.

©1973 ADAL/Smithsonian American Art Museum

In a 1973 self-portrait, ADÁL appears in his underwear seated on a wooden chair, his body appearing ghostlike; in place of his head is an opened umbrella. The image is accompanied by the work’s title, which reads “..and as I Began to Disappear, I realized Someone was Beginning to Forget Me…”

Caragol, the NPG curator, said ADÁL acted as “a bridge” between the elder generation who founded the Nuyorican Poets Café in the 1970s and artists like Pepón Osorio and Juan Sanchez, who first gained recognition in the 1990s. “The way he addressed identity in his portraits and in his work conceptually, there was an openness always. There wasn’t a definitive answer or a fixed idea of what Puerto Rican identity looks like,” she said.

Chicano photographer Harry Gamboa, Jr., a founding member of the artist group Asco, said, “As a photographer with an immensely artistic vision, ADÁL’s oeuvre presented a surrealist realm that contributed an inspired counterpoint to the increasingly absurd tempo of the 20th and 21st centuries.”

ADÁL, Muerto Rico, 2017.

©ADÁL

A recent work by ADÁL, who moved back to Puerto Rico around 2010, generated significant attention: Muerto Rico (2017) shows an individual submerged in the photographer’s bathtub. The person, whose name is Bold Destrou, wears a black shirt with the work’s title in all caps, which ADÁL spotted while walking in Old San Juan. Last year, the image won the People’s Choice award as part of the National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. It is part of a series assessing the island’s financial crisis, which was compounded by the damage wrought by Hurricane Maria in 2017.

In an interview earlier this year with Smithsonian Magazine, ADÁL said he had rediscovered a series of early self-portraits done while submerged underwater, which led him to want to create the new images of everyday Puerto Ricans underwater, titled “Puerto Ricans Underwater / Los Ahogados (The Drowned).”

“I said, ‘Wow, this seems to be what’s happening in Puerto Rico right now,’” he said in the interview. “Because at that point we had at one hurricane, and we had a really bad economic crisis. Puerto Rico is going through some major changes, and we feel like we’re disempowered … this is making things even worse.”

In his Smithsonian Magazine interview, ADÁL revealed that he had recently been hospitalized for pancreatic cancer. But he was determined to continue working on a new photographic series that looked at clouds. “I was looking at clouds from my hospital bed,” he said, “and felt like they were metaphors for transition and impermanence of things.”